This is where it gets bizarre.

How Customizable Should a Human Be?

Technology is raising fundamental questions that we’re not ready to answer.

Let me tell you three stories, and then let me ask you some hard questions.

The first story is this. In February of 2019, after 23 weeks of gestation in her mother’s womb, a baby girl was treated for the developmental abnormality known as spina bifida. Doctors at Cleveland Clinic in Ohio performed a delicate new form of fetal surgery which drastically improved what would otherwise have been lifelong discomfort and impairment. A computer-generated depiction of the procedure went viral and was greeted with joyful wonderment.

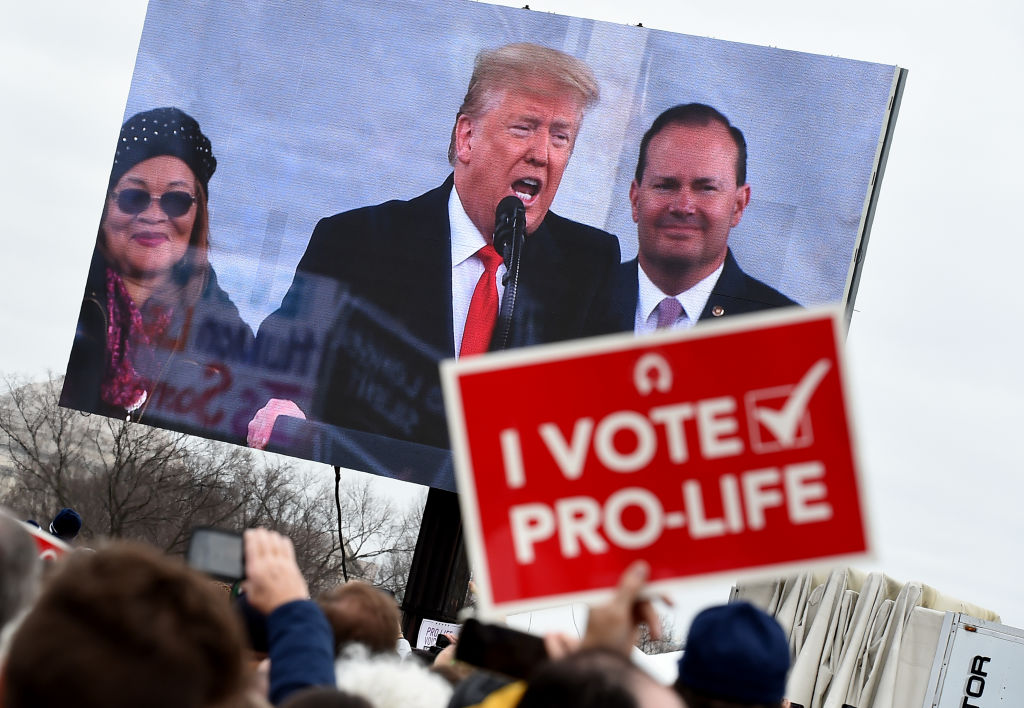

Here is the second story, a horror story. Last Friday, also in Ohio, a federal appeals court blocked passage of a law which would have prohibited doctors from performing an abortion if the mother’s reason for terminating her pregnancy was a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome. It is therefore legal for a mother to extinguish her baby’s life if she feels it will be beset with adversity. To read the ruling is to find oneself staring into the abyss of a society which would rather execute infants than be discomfited by their pain.

The third story is the strangest. There is a kind of bird, the zebra finch, which learns its pattern of song from its father. At UT Southwestern Medical Center, scientists discovered that by interfering with these birds’ neurological pathways they can implant false memories, making finches sing songs they never learned but think they did. Though there are no immediate plans to apply the technique to humans, the New Scientist reported that some researchers “hope we will one day be able to alter memories associated with psychological trauma.” If so, then people haunted by their past may someday be offered treatment to make them forget that past ever happened.

Here come my questions about all this. It seems to me that when science restores to our bodies the wholeness for which our souls are destined, then human resourcefulness reaches its highest consummation. We are born broken into a broken world, but we intuit that we were meant to be well. This is why our hearts leap up to see new technology which can repair spina bifida, or give sight to the blind: viscerally, we know science is here setting something right which was deeply wrong.

It seems equally clear to me that the state-sanctioned murder of babies with Down syndrome is an abomination that should make our children’s children ashamed to own us as their ancestors. Whatever the answer is to the injustices of biology, it is certainly not to spare the comfort of the strong by slaughtering the weak.

But between these two extremes of right and wrong there is a chasm of uncertainty, and that is the chasm of the songbird. Every day the technology with which we can predict and alter the development of biological organisms becomes more sophisticated. We are verging on a world in which all aspects of our physical, hormonal, and neurological constitutions will be up for editing.

The first question is, what should we change, and on what grounds?

For, though we are not merely bodies, we are wholly embodied. Our dreams, delights, and heartaches are encoded into physical structures—which now can increasingly be toyed with. If a man was abused by his father; and if the memory of that abuse lives in some quadrant of his neural network which can be isolated and annihilated; and if by that annihilation the man is freed from a lifelong sense of self-loathing—should he be? Is the ease of his mind worth the erasure of his past? Which of our wounds make us who we are and so must be preserved, no matter how bad they hurt? Which are alien to our essence and so should be healed for the glory of God?

Horrifyingly, there is a strain of thought in the West which holds that suffering should be eliminated at all cost: delete memories, splice genes, kill babies, if only it alleviates the contortion and agony that comes from being as we are born. If this is to remain our governing philosophy then the use to which we put our ever-developing scientific powers will be fearsome indeed.

There must, must be another way. But what is it? Down syndrome, gender dysphoria, homosexuality, depression, anxiety: it is not out of the question that we will soon be able to identify and “correct” all these eccentricities, and others besides, before the patient is even breathing. Once we can, we will have to ask, should we? Which ones? Why, or why not? According to what moral rubric?

Behind all these unknowns lie two fundamental questions: what is it to be human? What is it to thrive? If and only if we think seriously about the answers now, then there is yet hope for the swiftly approaching future.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Recent Supreme Court victories could signal a popular conservative resurgence.

In order to fight abortion, pro-lifers must fight the screen.

Pro-aborts will never forgive him for helping overturn Roe.

The Left aims to corrupt children for their own nefarious purposes.