AIDS awareness is only the secondary concern.

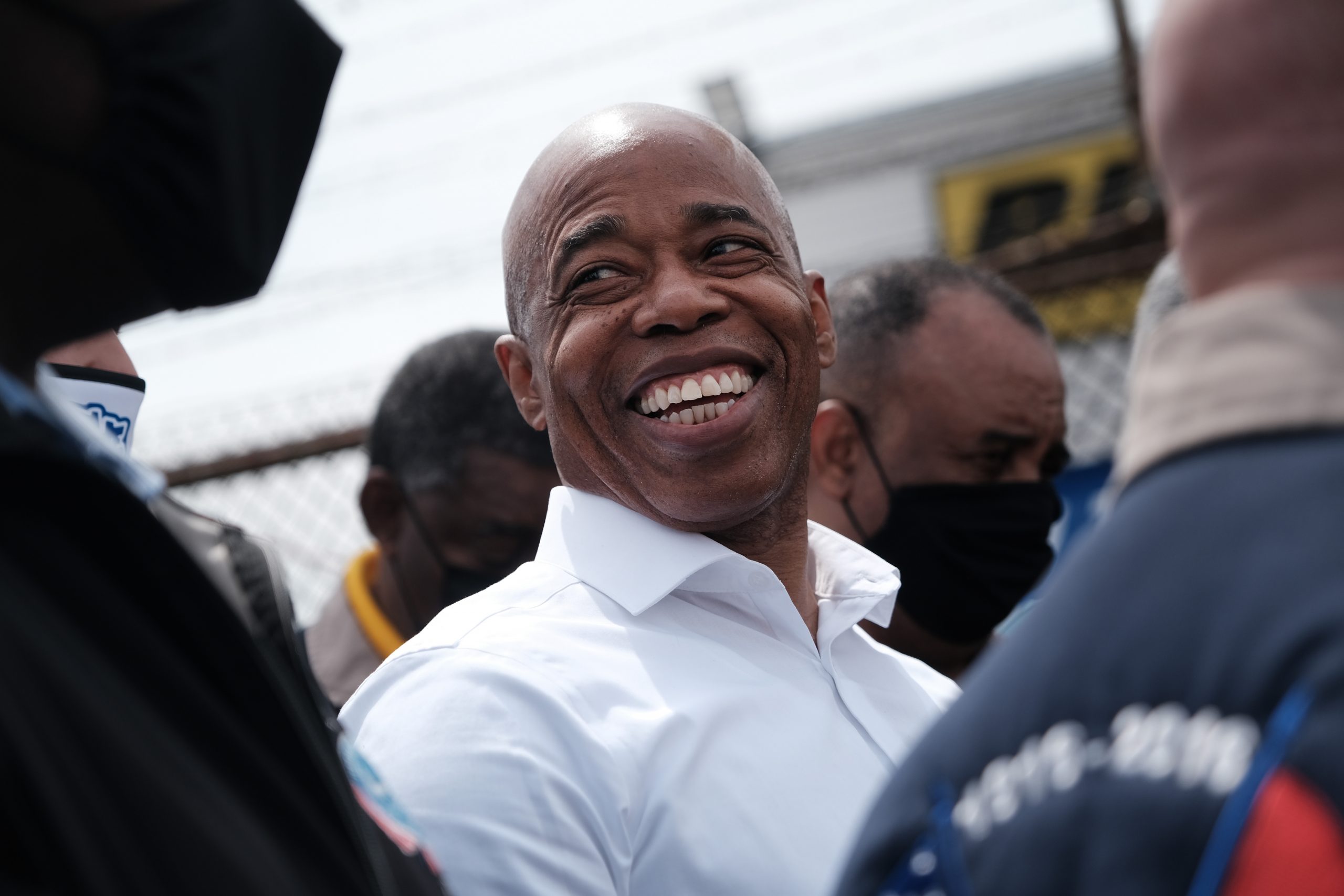

False Hope for New York

A closer look at Eric Adams’s odd history

Leaders of New York City’s business community were heartened this week when Democratic mayoral nominee and Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams came before them to promise that, under his administration, New York would “welcome business.” In keeping with his primary campaign rhetoric, Adams insisted that he would prevent the city from becoming “dysfunctional,” with a renewed focus on public safety.

These are welcome words. But a closer look at Adams’s campaign platform and long public record reveals a worrisome pattern of reversals, empty promises, and unfulfilled expectations that should at least temper voter optimism that New York City is turning a corner into sunshine.

For instance, while Adams vows to make New York City friendly to commerce, last year he co-authored a Wall Street Journal op-ed proposing a radical new corporate tax on information. “Years of chronic underinvestment in education, health care, housing and transit,” he wrote, challenge the city “to find new revenue sources.” The obvious place to impose new taxes, according to Adams, “is the data economy.”

The municipal budget has ballooned in the last eight years, growing more than 3 times faster than the rate of inflation, and spending on “education, health care, and housing” under de Blasio has been especially lavish. If the de Blasio years represent “underinvestment” in social services, it is hard to imagine what full investment will look like. And promising to tax the leading companies of the information age, “from big players like Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google to smaller startups and online merchants,” scarcely sounds like the development plan of an incoming leader who wants to attract new corporate jobs in big numbers.

As a former cop and an African American, Eric Adams gives many New Yorkers hope that he will be able to impose sensible law-and-order policies without fear of being labeled racist. But Adams’ career on the force was marked by hostility to police leadership, constant opposition to the practices of policing, and an insistence that the NYPD is a racist institution. For example, in 1992, Al Sharpton, who was running for U.S. Senate, hired Adams to protect him in his off-duty hours. Adams explained, “We are not going to permit another African-American leader to be assassinated by a racist system within the New York City Police Department.” It is not clear which black leaders who had been “assassinated” by racist cabals within the NYPD Adams meant.

This kind of inflammatory rhetoric continued into Adams’s career as an elected official. In 2013, while a state senator running for borough president, Adams denounced the NYPD’s stop-question-frisk practices as racist and ineffective. White men wearing suits, he explained, are not targeted by the police for stops, even though “they’re the ones bringing guns into black communities.” The reason “they can’t stop the flow of guns coming into the community,” he elaborated, “is because no one is checking the people bringing in the guns.” Hence the “ongoing genocidal murder in urban America” of blacks and Latinos.

It is important in this regard to recall Adams’s close ties to Louis Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam. While never a member of the NOI, Adams worked closely with the group in formulating an anti-crime approach. But in 1994 Adams did speak out in defense of Farrakhan’s deputy Khalid Abdul Muhammad, who called Jews “bloodsuckers of the poor,” and was removed from his position after Farrakhan received pressure from black leaders. But Adams minimized and deflected Muhammad’s statements, asking “the Congressional Black Caucus and others who insisted that Minister Farrakhan repudiate Khalid Abdul Muhammad to use their same lobbying strength to give him the assistance that’s needed to go into our communities and put in a true war on crime.”

Possibly the most bizarre and underreported episode of Adams’s career was his revival, in 1998, of the 1987 Tawana Brawley rape hoax. The case, which resulted in monetary judgements against Al Sharpton and other Brawley “advisors” for defaming Dutchess County prosecutors and police officers as her rapists, fell apart when the physical evidence and testimony demonstrated that the teenage girl had confected her story of abduction and assault. Nevertheless, a decade later, Eric Adams led a perverse campaign to demand a federal investigation into the case. “The hoax was not Tawana Brawley’s statements. The hoax is what has taken place during this investigation,” Adams announced.

I haven’t even mentioned his bogus “One Brooklyn” non-profit, which he used to raise money before it had even been legally constituted, or his neck-deep involvement—as chair of the senate Racing and Wagering Committee—in the 2010 Aqueduct “racino” bid rigging scandal.

Aspiring politicians say all kinds of things, and maybe Eric Adams shouldn’t be judged harshly on statements he made ten, twenty, or thirty years ago. On the other hand, though, his rather loose association with facts and apparent willingness to say virtually anything should give us pause before we rejoice in the return to normalcy Eric Adams promises the people of New York City.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Connecting the dots the experts won’t

Our useless ruling classes are making a hard decision way, way worse.

Biden’s handpicked banker declares war on digital freedom.