America’s blindness to the source of our decline is the fundamental problem we face.

Escaping From Reality

Apple Vision Pro is doomed to fail just like the Metaverse.

Although it’s hard to believe now, as Mark Zuckerberg continues laying off thousands of employees, there was a time when many people believed that the Metaverse, a fully-immersive virtual-reality platform, would revolutionize the way people lived. It seemed only natural that people who were already addicted to their screens and spent most of their waking lives online would want to take the plunge and connect to the Matrix indefinitely.

At the height of Metaverse buzz, I was one of the few who argued that it would flop. No, I’m not a technology or business expert. I’m just a humble believer in reality who can apply basic logic to different situations. When I saw videos of the Metaverse, it simply looked like a crappier, clunkier version of Second Life, a popular digital platform from the mid-2000s where people would make an avatar, traverse an imaginary landscape, and interact with other users. As with the Metaverse, many believed Second Life represented the future of social interactions (my alma mater even bought land in Second Life), yet in the end, it mostly became a space for anti-social nerds to act out their sexual fetishes—which seems to be the Metaverse’s destiny as well.

Now, with the announcement of the new Apple Vision Pro, a set of goggles that allows users to immerse themselves in a digital reality, I suspect it will flop just as hard as the Metaverse—and for many of the same reasons: it is inconvenient, expensive, and completely at odds with human nature.

To understand why the Apple Vision Pro (or AVP) will fail, it’s essential to understand what it is. No doubt, the company wants to portray the AVP as a magical gateway to an “augmented reality.” No longer will people need actual computers, televisions, or even most home furnishings; the AVP will superimpose these things onto floors and walls and make them interactive. AVP users will be like “Iron Man” Tony Stark manipulating interactive 3D holograms—except they will be wearing headgear instead of figuring out the mechanics of time travel.

It’s more accurate to see the AVP as an escape hatch from physical reality. Instead of expanding one’s perceptions of the universe that God created, it narrows those perceptions to the virtual universe man creates. Contrary to granting true “vision,” the AVP works like blinders, keeping users focused on the prescribed path designed by unimaginative programmers. As John Daniel Davidson observed in The Federalist, “users aren’t really looking through the headset at the world, they’re looking at a digital recreation of the world around them.”

Altogether, the AVP combines the functions of the smartphone, a big-screen television, and Pokémon GO—except that users must keep it on their heads and stay indoors. This drawback makes it extremely inconvenient. Whereas people today can stay connected anywhere with their smartphone, watch television with other people, and explore their neighborhood by looking for Pokémon, the AVP confines them to their sofa to do the same things all by themselves. And all at the ridiculous price of $3,500.

That said, even if the AVP were cheaper, could work anywhere, and not look stupid, it would still hardly qualify as more than a useless novelty. This is because, as bad and boring as the real world might be, human beings are still designed to live in it (hence we have bodies) and will always prefer it over an artificial copy.

This is the central claim made by Spencer Klavan in his recent book How to Save the West. People crave reality, and they are unhappy when that reality is substituted for something man-made. Ignoring this truth has led to five major crises afflicting society: that of reality, the body, meaning, religion, and the regime. Klavan attempts to provide answers to these problems by invoking the collected wisdom of Western civilization, all of which speaks to the timeless advice of keeping it real. In practice, this means rejecting the lies of transhumanism, scientific materialism, totalitarian technocracy, and especially virtual reality.

In a pithy yet readable essay entitled “Meaning and Truth,” theology professor Randall Smith reflects on this human yearning for reality, specifically as it’s illustrated in the classic sci-fi film The Matrix. He notes that Neo is the protagonist, because he takes the red pill and accepts reality in all of its ugliness, while Cypher, the antagonist, purposely rejects reality by taking the blue pill. “Rarely does someone root for Neo to take the blue pill and stay ignorant, or not find Cypher pitiful for choosing to return to unreality,” Smith writes. Even though Cypher’s desire to live in the Matrix as “a wealthy and successful man who enjoys pleasure with plenty of beautiful women” is understandable, it is also totally meaningless and selfish. Even if he was allowed to live out this fantasy, he would ultimately become bored to the point of despair and seek additional means of escaping reality—maybe even purchasing an AVP.

When entrepreneurs like Mark Zuckerberg or Steve Jobs recognize this central principle about people’s desire for reality, they profit enormously. Facebook was a user-friendly product that helped people stay connected with their social network; it didn’t replace reality but expanded it. The iPhone was an elegantly-designed mobile computer that a person could use anywhere; again, it didn’t replace reality but enhanced it. Indeed, this is what makes both of these innovations so stimulating and addictive.

When entrepreneurs or CEOs forget this, they will inevitably fail. They will just create a useless, uncreative product that no one wants. On the bright side, this outcome may cure the leaders of these Big Tech behemoths of their hubris and set them on a more constructive path of helpful innovation.

It may also encourage consumers to ask how much of their life is being wasted on things that aren’t real. So many devices that we think necessary for modern living are what Charles Carman calls “tools for enslavement,” things that are “inhospitable to human flourishing.” They complicate our lives, distract us, and pull us away from what’s real—even as they promise to do the opposite.

We should save our money and refrain from breaking the bank for an Apple Vision Pro. Nevertheless, we should also save our souls and reconsider the technology we use too much already so that we can immerse ourselves more fully into the world we were made to live in.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Identity politics can’t rule the digital swarm. What can?

Resistance is not futile.

Accepting our reckoning with our humanity and our technology.

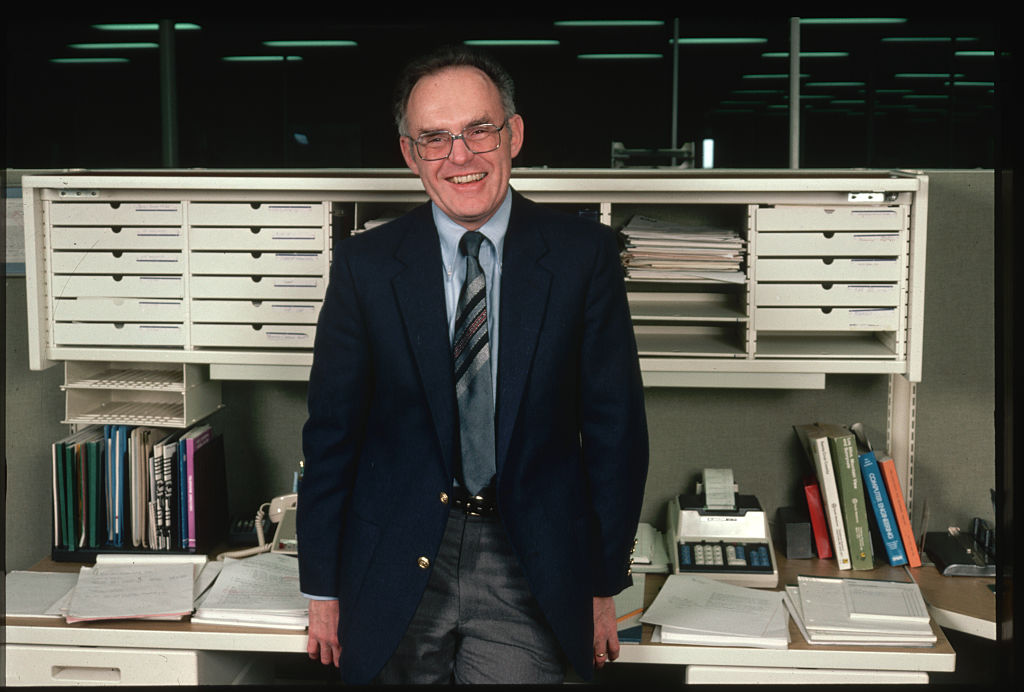

Gordon Moore was the last of the great twentieth century American innovators.

Big Tech poses a formidable challenge to maintaining self-government in the digital age.