Reviving the Hamiltonian spirit in an era of populism.

End D.C.

A modest proposal to eliminate the capital city

There is much talk about how to “fix Washington”: how the administrative state might be brought to heel and made accountable and responsive to the practical problems facing the American people. The election of Donald Trump is best understood as a populist effort to “fix Washington.” But Washington was not fixed. On the contrary. As we learned from the soft coup that was the “Russian collusion” psy-op, the two fake impeachments, Democrats’ condoning of the George Floyd riots, and the manipulation of the 2020 election, the administrative state has only grown more brazen, more authoritarian, and more abusive in its exercise of power since 2016.

Perhaps Washington can’t be fixed. But it can be dismantled. Do we need Washington D.C. as the central locus of national power? With enormous technological changes in how business is conducted and how communication works, it may be that a capital city is a vestige of an earlier era. Perhaps rather than working to fix D.C., we should work to end it.

The benefits of a decentralized government

Until recently, there would have been no way that the federal government could function without a centralized place to conduct business. But today, we shop online. We work online. For two years, people went to school online. If all these essential life activities could be moved to the internet, why couldn’t government? While one could argue that online education and similar enterprises have decreased the quality of the services they provide, it appears that online governance might enhance the function of our democracy.

A major reason that Washington can’t be fixed is what has been called the “monoculture” that obtains throughout the government. The culture of any place breeds conformity: to refuse to assimilate to a culture is to mark yourself as an outsider. Because the presence of outsiders threatens the maintenance of any culture, cultural insiders often withhold their approval from those who don’t conform.

Imagine that a new representative is elected from the state of Delaware. He arrives in the capital as an avatar for the culture of Delaware, which is not the culture of Washington D.C. Because he shares the interests of the people of Delaware, he serves as an effective representative his constituents. But D.C. institutions have a different way of doing things: a different way of governing, socializing, doing business, and influence peddling. This creates a pressure for our representative from Delaware to adapt. After all, if he doesn’t, he won’t earn many friends—and he may even find some enemies. And if that were to happen, his tenure in Congress could be very brief. He doesn’t want that. So, the longer he is in the capital, the more he acculturates to the D.C. way of doing things. This wins him friends, donors, and more elections. After 50 years of “public service,” our regular Joe from Delaware will be almost entirely unrecognizable to the people he used to represent.

Remote government by Zoom might be the best way to break this monoculture. If all the official proceedings of the legislature were conducted virtually, this would keep the officials in the states that they represent. Not only would they be more aware of the situation in their home states (since they’d no longer spend much of the year far away), they would be more accessible to their constituents. Regular physical contact with the people who elected for them would increase the accountability of officials as they serve out their terms. This would also impede the formation of close friendships with representatives from other states, and hinder coziness between our representatives and the lobbyist and consultant class that parasitizes the body politic inside the Beltway. These friendships—which the culture of a centralized capital encourages—create an opportunity for an elected official to develop personal allegiances, obligations, and favoritism that may run counter to the interests of the people he represents.

Still, it wouldn’t be enough to simply conduct official state proceedings virtually. It would be even more important that the business of unelected bureaucrats also be moved online. Right now, the staff of the Department of State, the Internal Revenue Service, or the Environmental Protection Agency is largely composed of educated urbanites, raised in the monoculture of the university and the eastern power corridor. Imagine if the mid-level clerks at the State Department weren’t all working together in Washington, but were spread out across the country, working independently from home: one in Kalispell, Montana, another in Little Rock, Arkansas, and another in Birmingham, Alabama. There would be no more potent way to erode the influence of the monoculture in government. Bureaucrats wouldn’t have personal relationships with most of the people they work with. Further, because so many colleagues would come from outside the monoculture, they wouldn’t be able to reliably ascertain where their political loyalties lie, which would discourage internal schemes. And the fact that one could never be sure that one’s online communication wasn’t being recorded or surveilled would be a strong disincentive for conspiratorial corruption. Finally, the tedium of online communication (emails, Zoom calls, etc.) would encourage workers to eliminate almost all inessential interaction, which would undermine the informal advocacy and organization that occurs behind closed doors in D.C.

There would also be a variety of peripheral benefits to be had from eliminating a national capital. As it stands, the capital city always represents a desirable target for hostile military action—this was tragically illustrated on 9/11 and various other occasions. With all government business conducted online, enemies of the United States would be deprived of an attractive hard target. Additionally, as we have recently seen, the courts of Washington routinely serve the objectives of the state monoculture. For cases that involve the interests of the federal government (which are often tried in Washington simply because the government is located there), the outcome is all but predetermined. But if the government wasn’t physically located in Washington, some other criteria could decide where these critical cases were tried, and juries could be drawn from places other than the capital.

The future of the former capital

Surely, there would also be some drawbacks to abolishing the capital, most notably that the basic functions of government would come to rely almost entirely upon the availability and quality of internet access. In some extreme scenarios, this could inhibit the ability of the state to respond to emergent crises rapidly and effectively. But as it is, no one would say that responsiveness is a major characteristic of the federal government in Washington.

What would happen to D.C.? It would still exist as the historical seat of government. All the great monuments of our nation, along with the Capitol, the White House, the Smithsonian, and more would still be there, ensuring that tourism remains a major source of revenue for the city and its inhabitants. The National Archives would still hold the great documents of the Founding. The federal district could take on the status of the Tower of London in Britain as an official, ceremonial representation of the power of the United States; or like Kyoto in Japan, as a historical center of the nation. Many nations build new capitals to reflect new domestic needs. Egypt is currently building its “New Administrative Capital” to relieve congestion in Cairo, and Indonesia is relocating its capital from Jakarta to the new planned city of Nusantara. America will do something new, extraordinary, and cutting-edge: we won’t move the seat of political power, but devolve power to the provinces.

It increasingly seems that the very function of having a capital in our era is to protect and nourish the monoculture that makes DC seem so remote—politically, culturally, and geographically—from so many of the Americans that the government purports to represent. Dissolving the capital could reduce the corruption that is now implicitly associated with any mention of “Washington.” This could be a great step forward for our democracy. Somewhat ironically, decentralizing the federal government might make it feel a good deal closer to many of the people it serves.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

GOP “leadership” are the regime’s loyal opposition.

Our useless ruling classes are making a hard decision way, way worse.

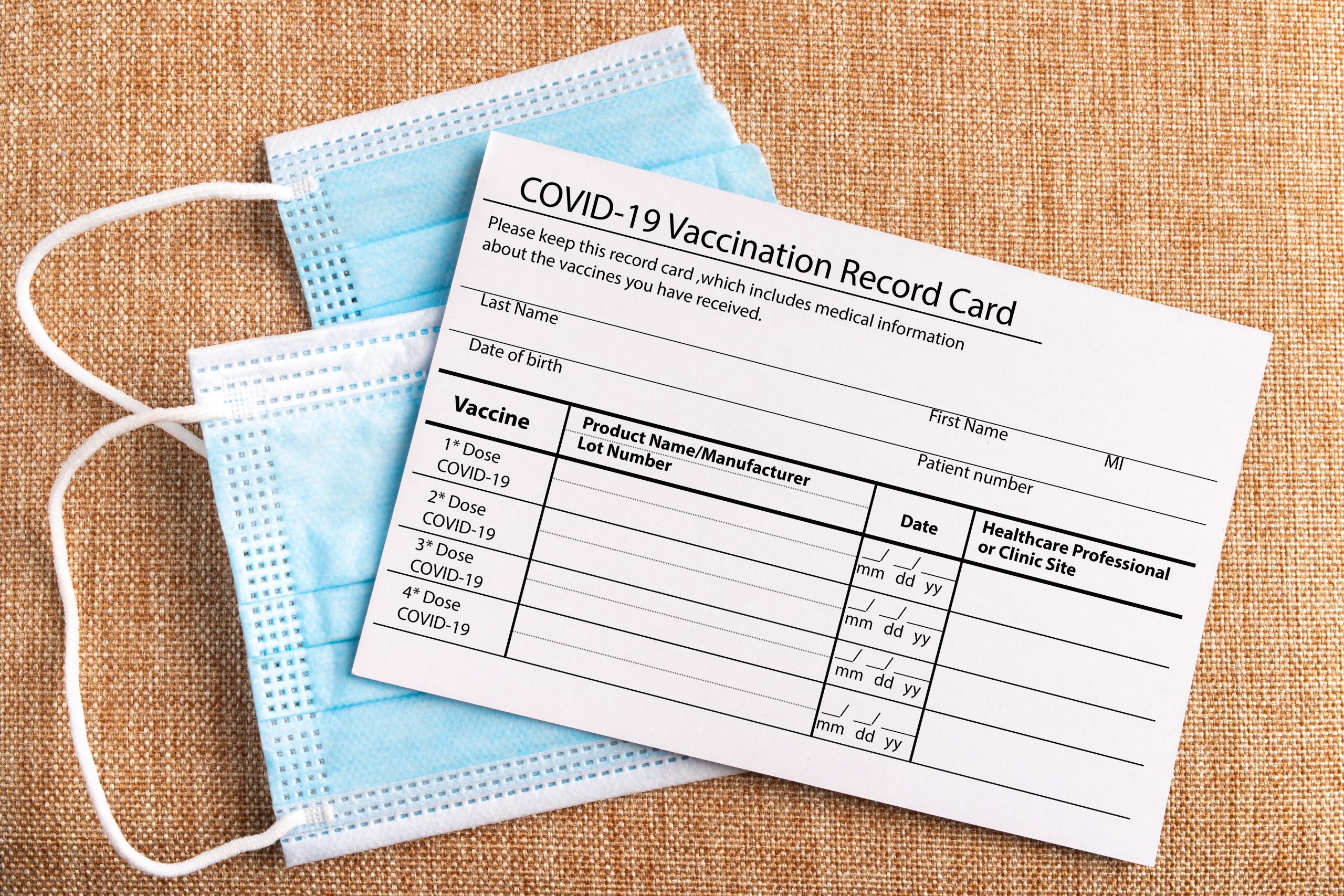

Inside America’s mortality misinformation crisis.

The definition of online freedom has been depressingly constricted over the last thirty years.

The regime is set on full-spectrum destruction of its enemies.