Our corrupt elites have stolen the valor of American heroes. Time to take it back.

Empire’s End

The intervention in Iraq was worse than a failure; it was hopeless.

This is the second in a two-part series detailing the author’s recent trip to Iraq. See the first part here.

In Mosul, I asked a man my age what he thought of ISIS. I was trying to be as unassuming as possible. “Good?” I said with my thumb pointed up, “Or bad?” inverting my hand. “They killed my mother, my father, my brother, and they torched my car” he said in perfect English—no thumbs necessary. He then went back to playing PUBG on his iPhone, a video game I’ve seen elsewhere in the Middle East, where the goal is to kill everyone participating.

Mosul was the most beautiful city I visited in Iraq, and the most destroyed. Because of previous warnings, I spent the first day with a guide name Ahmad, although Mosul actually seemed much safer than Baghdad. Ahmad normally works as a doctor, which makes him the equivalent of thirty dollars a day. He’s hoping to leave his career as a healer entirely and become a full-time guide of what he calls “dark tourism.” (You can only sell what you have.) At least as a guide he makes fifteen dollars per hour.

Ahmad had tried to make a run for it while the city was under ISIS control. His circuitous route was to smuggle himself across the border into Aleppo, then again into Turkey, and then somehow make his way back into Iraq where he would hide out in Baghdad. But Ahmad got caught five minutes from home. The Jihadists put a gun to his head, as an incentive to tell the truth, and in response Ahmad lied by claiming he was only visiting a friend just west of Mosul. That friend was then brought in and also interrogated with another gun held to his head. Ahmad was amused by telling this story. “We both should have been killed,” he said through laughter.

We began the tour in the main market, walking past stalls that were selling rolls of sheeting and fabric. Ahmad turned to me to ask if I knew about Benito Mussolini. “Yeah, the Italian” I said casually, suppressing my excitement. It turns out that the name Mussolini was derived from the cotton weave Mussolina (“Muslin”) which originated in Mosul. These are the kinds of geography facts omitted from standard curriculum. Though perhaps this fact is better suited to the realm of history, because whatever materials that are now sold in Mosul are imported from China.

Because I mentioned my casual hobby of blacksmithing (incidentally something else common in Benito’s genealogy), I was then taken to the quarter where hot steel is pounded into commissioned forms, mostly to create structural supports for the local construction in the Old City. One of the workers was surprisingly muscular, even for a blacksmith. Talal Hassoun first started off as a weightlifter, competing in the 1980 Summer Olympics. On the walls of his forge were stapled pictures of himself as a young handsome man, very lean and built more like a bodybuilder, when he competed at the highest level. The blacksmiths wanted to see me work, too, so I spent an hour smashing white hot iron to their delight.

The men in Mosul seem to work much harder than in the capital or in Erbil, which are two cities teeming with Bengali and Bangladeshi migrants. I was told by a Nigerian social worker that many international work agencies had promised European visas to desperate Africans and Asians, only to send them Iraqi ones instead. As if they weren’t unlucky enough. But the practice in Erbil was eventually stopped by the government in response to public pressure, because the job market became overwhelmed by foreign workers. (I wonder if Arabs have yet written their own The Camp of the Saints?) Employers had to stop playing bait-and-switch. Though this kind of nativism was common outside of Kurdistan too. Even my guide was fond of saying: “In Mosul we are a little racist,” whenever there was an opportunity to denigrate lesser people, including other Iraqis, whom he perceived as part another race.

I had much better food in Mosul than elsewhere. Though that was likely because I was being shown around. To eat out in Iraq means to eat with men. The public is not for women. And a vegetable is a rare ingredient. It’s meat and bread with maybe a grilled tomato and some raw onion. The meat selection is also limited to either kebab (options: beef or chicken) or shawarma (options: chicken or beef). The diet here is low enough in fiber that intestinal evacuation can also be something of a workout. Although the squat is supposed to be more physiologically conducive than sitting, so perhaps it all evens out.

There were some notable meals. The meat pie Kubba Mosul was my favourite. A very flat disk made from bulgur and wheat, boiled in water, containing lamb and onions. It is a very old recipe, and descriptions of Kubba have even been found on Assyrian tablets. Another good dish was Kas (pronounced locally as “Gus”), which is a spicy rich broth ladled into a bowl of torn pita and topped with shawarma shavings. It is heavy and eaten early in the morning. The largest meals of the day are eaten after the Fajr prayer, the earliest of the five prayers, which takes place between dawn and sunrise. I otherwise had some pistachio ice cream that was excellent, though I wouldn’t exaggerate by comparing it to the Sicilian variant.

The Old City of Mosul is now a misnomer: not a city; but a sea of ruins. Where once there existed beautiful homes, now stand many piles of rock. Though the rubble can give the illusion of raw damage, since many piles have been made by bulldozers clearing the area for reconstruction, which are still turning up the occasional forgotten corpse. In the debris some tokens of previous inhabitants protruded. These might have been the possessions of original families, or the belongings of the Islamic State, or the items discarded by the trouncing military, all left behind in the wake of war. It was also very hard to tell any difference between a genuine artifact and a pseudo-relic, because so much additional garbage has been heaped on.

I badly wanted to find an ISIS flag to adorn my wall. Something to complete the internationalist living room and mock the cosmopolitan traveler who uses collected items to flaunt exaggerated experiences to equally smug guests. I could just picture myself back at home:

“Yes, and next to the Iroquois quillwork and Malian mud-cloth is The Black Banner emblazoned with the Shahada. Indeed, the symbol of yet another minority resistance group crushed by neocolonialism and big capital…more wine?”

I searched through some wreckage avariciously but found nothing. This kind of archaeology could only be done late in the afternoon when the military ended their patrol and no one was around to stop my entry. Perhaps it was for the best, however, because to be caught with any ISIS memorabilia is a serious offense, and seeing the inside of an Iraqi prison was not on my to-do list. I was also informed that some sought-after items did not even exist outside the fantasies of Western media, like the officially minted ISIS coins, which were made only to project legitimacy to gullible journalists.

But beyond searching for mementos, the Old City is a beautiful place to simply walk through, and I spent most of my time exploring the ruins. Some buildings are defiantly still standing, though completely dilapidated, and have maintained their posture like snags in a deadwood forest. Every home in the entire area has been completely effaced by projectiles, and often slabs of concrete overhang the street, dangled by a single strand of rebar, like the way an ice chuck clings to the straw reeds of a thatched roof.

The desolation of the city has brought about a tranquility too. It is the only place in Mosul, without people, that isn’t bustling with mundane urgency. Even the ruins have a pleasing and serene look. The homes were built primarily from three natural stones: a sandy limestone; the Mosulian Marble, which is white with tea-stain-coloured veins; and the translucent but milky crystalline flint. All mixed together now, from the upheavals caused by numerous storms of steel, the whole city glows a monotonous off-white under the bright sun. With the uncanny silence, it gives a dreamlike bliss to the destruction.

In many traditional homes there were open courtyards. These blockhouses had their exterior walls coated in smooth plaster, an aesthetic that is very harmonious with the austere desert environment. The interiors were at one point very ornamental. They are now tattered by war, including the basements and bedrooms—maybe the evidence of close-quarter gunfighting, or executions, or maybe just men shooting at the walls to relieve boredom during intermittent peace. Now only homeless dogs and wild cats occupy the remains, some of which were irritated by my trespassing.

Throughout the city there are signs by UNESCO, boasting its leadership in the reconstruction effort, with their listed partners such as the Government of Canada and the European Union. It is all being done under the tacky slogan “Revive the Spirt of Mosul” which, for the price of one, also includes an educational plan. You have to ask: which spirit are they trying to revive? Maybe the Mosul of Assyria during the reign of the Achaemenid Empire. No? Perhaps the spirit of the early Islamic conquests of the seventh century. Not that either? Of course not.

UNESCO is on the predictable mission of importing into Iraq the same universalist ideology that has crippled the West. You can hardly read UNESCO’s Mosul memos without coming across trite buzzwords in every sentence, such as “cultural diversity” or “pluralistic identity” or “co-existence.” I doubt they recognize that these soft-power attempts at inculcating “modern values” are precisely what feeds Islamic reactionary movements in the first place. Or if they are aware, they are simply too convinced of their own propaganda, which they proselytize to these desert dwellers.

The most conspicuous displays by UNESCO are surrounding The Great Mosque of Al-Nuri, the place where Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi announced the new caliphate while raising the ISIS flag above the spire of its famous, leaning minaret. It was a short-lived victory, however. Because the Islamic State exploded the whole mosque in 2017 as they retreated. Like Saddam setting his torch to the oil wells in 1991 and 2003, the defeated prefer to leave nothing to their enemies. Only the Dome was spared by miracle (or by incompetence) since 600 kilograms of dynamite failed to detonate. Today the tilted minaret is only visible in pictures or on the reverse side of the third largest Iraqi banknote, the Islamic-green ten-thousand-dinar bill, which was introduced in 2003 around the time of America’s invasion. It is another instance of time playing an ironic game. Because the toppling of Saddam was, in some way, the first domino-flick in the creation of the Islamic State. Once in control, the Americans disbanded the Iraqi military, and thousands of Sunni soldiers found new employment under the auspices of the insurgency veteran Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi. Zarqawi is putatively the Islamic State’s late-grandfather since—after his deadly conference with two laser-guided bombs, courtesy of the Red, White, and Blue—his war-band eventually became the group of strident militants fighting for Baghdadi’s caliphate. What is also rarely mentioned is that much of the destruction of Mosul came from American or America-supported airstrikes. In particular, a bombing campaign on one spring day in 2017, to liberate the Old City, that killed nearly 300 civilians but spared the local synagogue. This is something the Islamic State had predicted: it is where they stored the bulk of their munitions. They knew that the Jewish temple was an unacceptable target for the annihilating red buttons, which are otherwise so eagerly pressed by the United States.

There are of course eccentric theories that suppose America has always known exactly what it was doing. Not only in the past, in the case of deposing Saddam and despoiling Iraq’s rich subterranean reserves. But that America, with impossible amounts of cunning, created the Islamic State in the Levant as a beacon to concentrate Islamic terrorists in one location and make it easier for extrajudicial purgation. With whatever suspicions remaining among Iraqis, however, and some that are more probable than others, it is now all just casual conversation—at least for the time being. The men in Mosul are instead putting their real energy into rebuilding their city, with the optimism that requires a willing amnesia.

ISIS Dreams

I can think of at least two reasons why the Islamic State became so fascinating—dare I say even seductive—not only to their targeted demographic, but their non-intended audiences as well. It was something that the parochial pundit machinery never understood, as they shrieked about the savagery of various execution methods and the Islamic State’s deliberate barbarism. On the one hand—and the hand that severed heads—there was something refreshing in the political honesty of the Islamic State, even their embraced brutality. They killed without dubious moral justifications (to which we are so numb) as a matter of removing enemies in the way of territory and power. On the other hand, ISIS, more than any other group, signified the frightening end—of the End of History. A welcomed termination, too, in my opinion. There had been other examples that had presented antitheses to liberal-democracy’s permanent hold, but none as recent with such evocative power. Though the Islamic State could never succeed with its complete rejection of modernity—and the delusion of “return” to archaic Islamic ways—it demonstrated an instinct which refused the ideology of the Last Man, even if that instinct was expressed by primitive people and a worn-out religiosity.

What made the Islamic State standout, more than any other Muslim insurgencies, was their widespread success in the recruitment of wannabe Wahhabists. Over 40,000 international fighters travelled to Iraq and Syria, to kill or be killed. And success could be attributed almost entirely to their social media operations, especially their high-quality propaganda, showcasing men in sleek military uniforms rolling through conquered towns in armored vehicles.

Of course, the entire ideology of the Islamic State was regressively stupid. Most of Mosul despised ISIS because they governed like pious cavemen, more concerned with policing beard length and other outwardly religious displays, while failing to inspire an actual frenzy of devotion. They were not only petty but also brutal occupiers, killing for small and mean reasons, and offering little to their people to gain support. Often citizens were arrested on suspicion alone, many of whom were tortured or killed, creating a relationship in which even supporters became paranoid.

The reality is that the Islamic State was doomed by its total reactionary orientation—the promotion of an exhausted religion while finger-wagging about morality—as a long-term solution in revitalizing a civilization. (This is something Christian Nationalists fail to understand.) Still, the Islamic State’s methods of disseminating their ideology were successful, because they used modernity to their advantage; in sum, they had an exciting way of spreading very stale ideas.

The point is moot, however, because the Arabs have no real future. They are currently a people without the potential for ethnogenesis, like the so-called Native Americans, who live as an anachronism. Genuine Arab life is now impossible, incompatible with modern life, and therefore only a romantic fiction. Iraqis seem to have only three orientations—and all three are completely hopeless: some have leaned towards Western liberal-democracy, fetishizing the strain of political ideology that has raped and ruined their culture; others want to walk backwards, like ISIS, and simply wish away modernity; most are just exhausted and drained of any vitality.

There seems to be no other Arab or Muslim alternative. The Arab will not, or cannot, adopt modern ways, let alone break through them with any historical vision. Even Iraq’s military ground forces, who have the proper outfitting and were trained by American instructors, are not really soldiers. Though men in uniform are all over the country—proudly sporting Ba’ath party moustaches, with Punisher stickers slapped to their thirty-round magazines—they are incorrigibly Arab. They leave their posts to smoke shisha. They accidentally sweep you with their rifles. They sit cross-legged on the sidewalk to eat lunch. I even saw one soldier at one busy intersection hanging his rifle by its sling and kicking the stock, to pass the time in the same way a kid might with a ball tethered by a string. An Arab peasant in uniform retains his peasant ways. This wasn’t always such a bad thing. “The perfectly hopeless vulgarity of the half-Europeanised Arab is appalling. Better a thousand times the Arab untouched,” was once remarked by T. E. Lawrence, and I probably would have shared the sentiment if such an Arab now existed. But it is impossible to meet anyone “untouched” in the modern world. There are no innocent cultures uncontaminated by the specter of what we mistakenly call “globohomo,” but what is in reality a much older spiritual disease.

Of course, there are good things to say about Arabs as well. Any orientalist’s essay is remiss without trite observations about Eastern hospitality. So let me be accused of the same. The Arabs, who are only one step removed from their Bedouin past, still show an exceptional warmth to foreigners. Americans included. The men like Ali, for whom resentment still lingers, are exceptions. There were several instances of Iraqi men who, although very poor and falsely convinced of my American provenance, were willing to share with me what I would have never shared with them. They gave without expecting anything in return, that calculated reciprocity, which taints generosity or negates it entirely. It is the kind honor that made me ashamed of my own parsimony. Something else commendable about this part of the world is the presence of strong male friendships. Perhaps the poison needs more time to show its effects, but the fracture set between boys is not yet apparent. This is also why militias are commonplace. But these compliments about the charming Arab character are made in vain, because the Arab himself is evaporating in this desert country. The causes are many, but the torrid sun is not one of them, and the shriveled husk that remains will reveal a man that is more brutal than what we’ve seen already, in evermore confused forms.

And so, what’s next for Arabs? Unfortunately: nothing. Circling the drain. Like forgotten species, long extinct, there are groups of entire people destined to share the same fate. (A prognosis just as acute and terminal for the Western man, too, unless something improbable changes his course.) This is the reality behind Ali’s cynical words, which are worth repeating: “Today will be better than tomorrow, and tomorrow will be better than the day after.”

The apocalypse is never a single event; it is an unraveling—well underway.

Correction: The piece originally stated that Talal Hassoun was an Olympic medalist. In fact, he did not win any Olympic medals.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

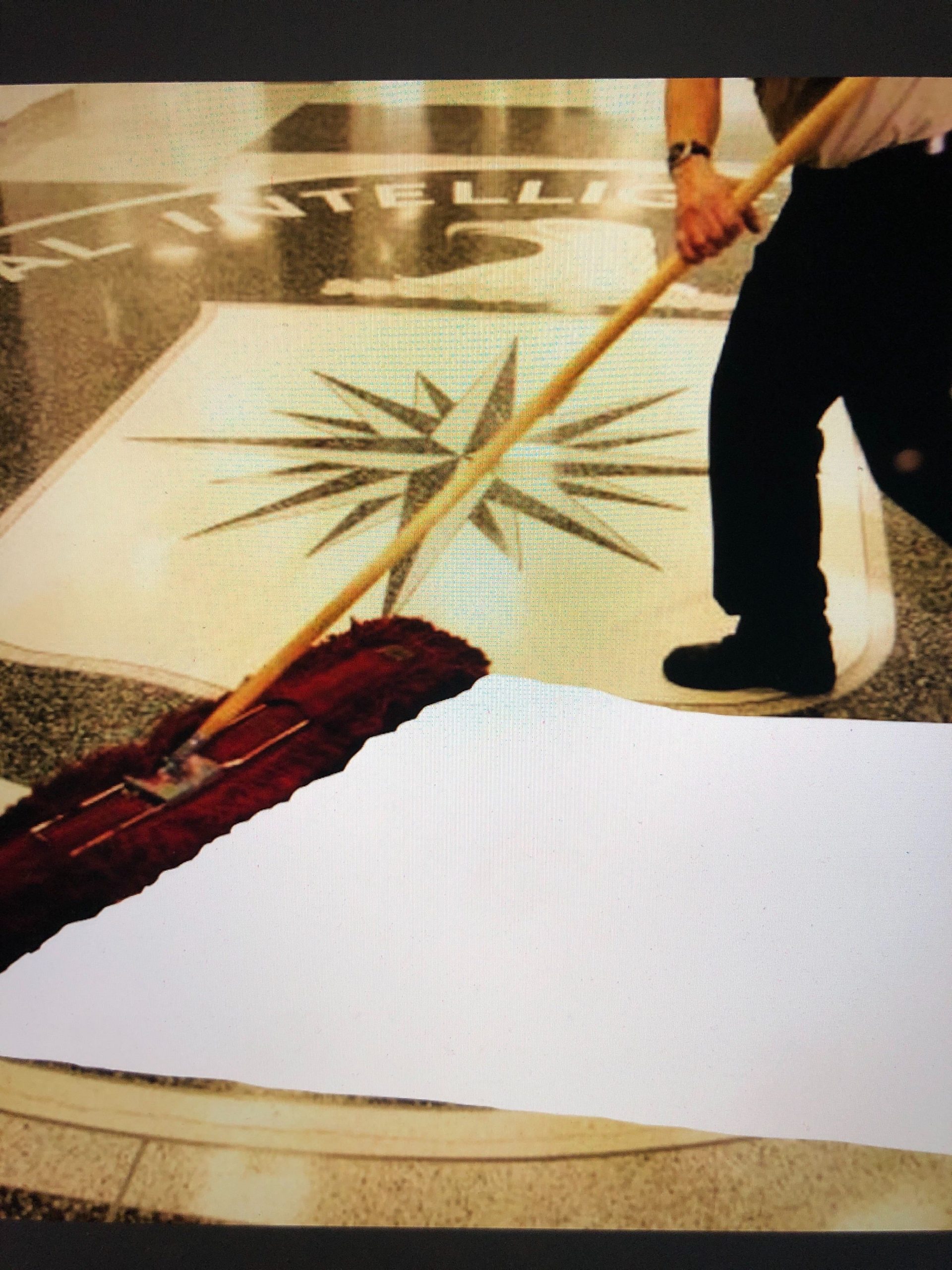

How to defend the Republic against the Deep State.

Afghanistan, et al., for the record