Daniel Webster’s Natural Rights Nationalism

Teaching the world the value of liberty.

The American Founders freely acknowledged that natural rights were granted by God—“endowed by their Creator,” to use their language. They and their early republic successors saw the United States as an example to the rest of the world in practicing the art of self-government. But what bears remembering in our own day is that they did not believe the United States was a home for all the world’s freedom-loving people. Instead, constitutional nationalists like Daniel Webster understood the U.S. as a teacher of mankind, a republican people seeking to pass along the blessings of liberty they cultivated to their posterity.

Due to an explosion in unrestrained Enlightenment universalism, Democrats of Webster’s day wanted to obliterate national borders and all non-democratic governments. Webster affirmed those same universal natural rights, but believed they could only be truly expressed through the particular history of the people of the American republic. It was not America’s job to tear down borders or obliterate national distinctions. It was America’s duty to teach all nations the value of natural rights by their example so that every nation might embrace natural rights in its own particular way, through its own institutions.

America was a nation founded upon universal principles, but those principles could only be truly expressed through the historical development and experience of the particular people who called themselves Americans.

In Webster’s time, American opinion was deeply affected by the Young America movement. A caucus in the Democratic Party committed to American imperialism for the cause of worldwide liberal democratic revolution, the Young Americans saw all non-democratic and non-liberal governments, all historic human inequities, and all non-American governments as targets for regime change. Young American ideologues like Democratic journalist John O’Sullivan hoped that America would eventually lead the world into a liberal democratic utopia.

O’Sullivan announced that America was

the nation of progress, of individual freedom, of universal enfranchisement. Equality of rights is the cynosure of our union of states, the grand exemplar of the correlative equality of individuals; and while truth sheds its effulgence, we cannot retrograde, without dissolving the one and subverting the other.

The United States “must onward to the fulfilment of our mission—to the entire development of the principle of our organization—freedom of conscience, freedom of person, freedom of trade and business pursuits, universality of freedom and equality.” That universalizing mission was “our high destiny, and in nature’s eternal, inevitable decree of cause and effect we must accomplish it. All this will be our future history, to establish on earth the moral dignity and salvation of man—the immutable truth and beneficence of God.”

O’Sullivan’s progressive Great Nation of Futurity delighted Democratic Party wardens in big cities, who saw immigrants—in particular Irish immigrants—as a source of near-endless voters who would drown the nationalist Whig opposition. Daniel Webster did not trade in the cartoonish stereotypes that nativists engaged in, nor was he a religious bigot. But he did believe there was a historical American nation, formed not so much through blood and soil as through time and custom, that deserved to be protected and perpetuated. Freedom, Webster knew, could not be bestowed on just anyone.

For Webster, those peoples ready for the liberties guaranteed by the American republic were pious, self-governed, and aware that liberty had moral limits. Webster told fellow attorneys in 1847 that liberty “exists in proportion to wholesome restraint.” His firm but open-handed constitutional nationalism, tolerant as it was, was nonetheless nationalism. Webster defended the American nation against any threat he saw endangering it, from secessionist Southerners to Europhilic democratic ideologues. His recent biographer, Joel Richard Paul, argues that it was in Webster’s brilliant oratory that the contending ideas of material, continental, populist, and cultural nationalism found their unity.

The Founders, Webster argued, were hardy and resolute men whose principles of civil and religious liberty would “spread wider and wider, until they shall brighten and bless all the nations of the earth.” But American liberty was not to be given to just anyone. Webster reminded his fellow citizens that “God granted liberty only to those who love it, and are always ready to guard and defend it.”

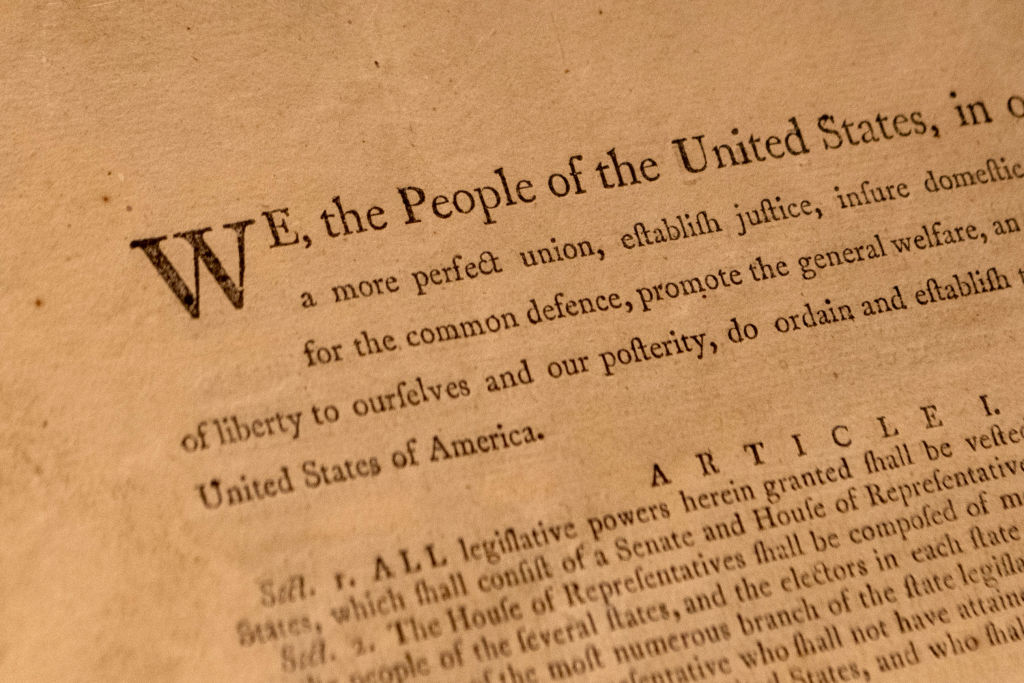

The United States Constitution did not make the American union a force for global liberation, nor was it meant to be a global ward of oppressed people everywhere, even if Americans sympathized with a desire for self-government and the pursuit of natural rights in other nations. No, Webster understood the Constitution as a trust given to the American people, by the American people, and for the American people. This argument was at the heart of Webster’s nationalism and his unionism.

At the dedication of the cornerstone of Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown, Massachusetts, in 1825, Webster emphasized a generational continuity among Americans. Fathers who fought in the American Revolution passed the duty of preserving American liberty to the next generation. “Venerable men!” declared Webster, “You have come down to us from a former generation. Heaven has bounteously lengthened out your lives, that you might behold this joyous day.” American constitutional liberty was not something that could be given to other nations, but a trust to be honored, nurtured, and protected. The civilized world, hoped Webster, “seems at last to be proceeding to the conviction of that fundamental and manifest truth, that the powers of government are but a trust, and that they cannot be lawfully exercised but for the good of the community.”

Biographies of Webster note his essential conservatism. Rapid social change, Webster believed, would shake social and cultural foundations that formed the structures of constitutional democracy. New England planted its democracy in the Puritan commonwealth; Virginia and Carolina planted their republic on the planter class’s republican aristocracies. But they all shared essential building blocks for American constitutionalism: a hatred of absolutist monarchy, a love of the English language, and an awareness that Christianity was necessary for socio-moral formation in the American order. The Bible, said Webster, “is a book of faith, and a book of doctrine, and a book of morals, and a book of religion, of especial revelation from God.”

Webster never lost the sense that he had inherited the stewardship of the American order from his cultural and political fathers. As Webster told his Senate colleagues in the midst of the debate over the Compromise of 1850, “Never did there devolve on any generation of men higher trusts than now devolve upon us for the preservation of this constitution, and the harmony and peace of all who are destined to live under it.” He knew it was up to him and his comrades to “make our generation one of the strongest and the brightest links in that golden chain which is destined, I fondly believe, to grapple the people of all the states to this constitution, for ages to come.” Webster knew he was chained not to the rest of the globe, or merely to blood and soil, but to the customs and practices received by the makers of the Constitution, and to the Puritan fathers who went before them.

Webster’s object was not racial. His was not a nation of immigrants, nor a nation that rejected immigrants. It was a nation that taught other nations to claim natural rights for themselves. Webster’s object was always “our country, our whole country, and nothing but our country. And, by the blessing of God, may that country itself become a vast and splendid monument, not of oppression and terror, but of Wisdom, of Peace, and of Liberty, upon which the world may gaze with admiration for ever!”

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

America must be refounded—again and again.

Part I: Unfettered reason cannot conserve anything.

America is neither unreservedly an empire nor altogether a European-style state.

A response to Angelo Codevilla.

Trump’s call to end birthright citizenship is a necessary corrective.