Spend your life preparing for death rather than ignoring it

Catholicism, Textualism, and Republicanism

Catholics can—and should—support both.

As the philosopher says (Rhet. I, 1), “it is better that all things be regulated by law, than left to be decided by judges.”

Originalism: the Common-Good, Catholic, Conservative Jurisprudence

In a recent article called “Vermeule, His Critics, and the Crisis of Originalism,” Hadley Arkes defends Adrian Vermeule’s attack on constitutional Originalism. The tenor of the debate suggests that conservative, Catholic, “common good” jurisprudence militates against Originalism. But neither Arkes nor Vermeule establishes any such thing. Instead, they both take an adversarial posture against the Aristotelian provenance of the common good.

Arkes and Vermeule misdefine “the common good” within the three-branch republic: they presume to surrogate unelected jurists for duly elected lawmakers. Judicial restraint be damned.

The late Catholic Justice Antonin Scalia once termed his jurisprudence—original public meaning—“the only game in town.” All texts—but especially constitutions and laws—must be scanned word-by-word for their objective (i.e., public) definitions (i.e., meanings) confined to the date of their ratified (i.e., original) usage. That way, the public meaning of a constitution holds its many ratifiers to their word, not just its few authors.

There is therefore only one licit form of amendment: amendment.

There are two major ways to practice Originalism: “intentionalism” holds that the intent of a text’s author(s) fixes the meaning, irrespective of the public signification of its words. Other originalists, though, are “textualists.” This is a philosophy of interpretation which holds that words mean what a generally intelligent person would plainly understand them to mean. Originalists who are also textualists reject the intentionalist approach, because they believe words are best understood as they were understood by the generally intelligent public at the time of ratification—never mind the authors’ intent, esoteric and idiosyncratic as it may have been.

Textualism presupposes a Catholic epistemology and metaphysics of moral realism: Arkes says that “Vermeule’s critics write as though any move beyond the text of the Constitution simply propels judges and legislators into a domain of utter subjectivity, bereft of any real truths to test and anchor our judgments.”

Quite.

Textualism presumes a Thomistic interpretive framework sustaining “real meaning.” Yet Arkes and Vermeule insist that Originalism requires a positivistic materialism which would actually destroy the basis for original, public meaning altogether.

Arkes (and Vermeule) seem to me to closer to a competing jurisprudence called “legal realism”—which plays far more intimately with the positivistic materialism they fear—wherein judges and magistrates do, in fact, recur to their own “utter subjectivity,” applying “smell tests” rather than Constitutional strictures and axioms of construction, in either affirming or striking down a given law.

It was, at root, legal realism predicated on “substantive due process” which gave us the following judge-made atrocities, things that could have never occurred under a textualist understanding of the U.S. Constitution: the “right” to purchase/use contraception; the “right” to pornography; the “right” to abortion; the “right” to sodomy; the “right” to gay marriage.

The textualist form of Originalism is intellectually, ethically, and metaphysically in line with Catholic thought, despite recent ambushes from right-leaning Catholic intellectuals. The intentionalist form of Originalism and legal realism (i.e. simple, judicial relativism) are not.

Post-liberals on the Catholic Right who dispute Originalism need to grapple with two issues. First, their misunderstanding of legitimate political regimes precludes three-branch republicanism (which privileges the legislature over the other two branches). Second, postconciliar Catholic intellectual life requires an explanation for the aporetic and enigmatic constitutions of the Second Vatican Council—an explanation which evades and dispirits all Catholic observers except for textualist-originalists, who alone can show continuity before and after the Council.

The Postliberal Regime Problem

In the 2300 years of natural law separating Aristotle from Adrian Vermeule, the most important Catholic thinkers have confirmed the ancient axiom that there are three salutary constitutions under which a regime may be justly founded (and three tyrannical types which descend from the same).

There is just rule by the one (monarchy), by the few (aristocracy), and by the many (republicanism). Aristotle, Plato, Isidore, Thomas Aquinas, and Pope Leo XIII explicitly embrace the above three “good regimes”; Cicero, Augustine, Bellarmine, Mariana and the Salamancans, and Suarez implicitly affirm them. A fledgling civil society may “take its pick,” as it were, among the three good regimes—or a “mixed regime” with elements of each in its three branches.

The lodestar of just rule running through all three regimes is the common good: a legally codified acknowledgement of the universal dignity and localized solidarity of all citizens—with the right to be governed by one or more of their nearest neighbors—known as subsidiarity. Note how this arrangement includes as its structural elements the four principles of Catholic social teaching: the common good, dignity, solidarity, and subsidiarity.

These are respectively the final, formal, material, and efficient causes animating the Catholic social architectonic. For all their structural differences, each of the three good regimes motivates the selfsame telos (final cause) of the common good, with subsidiarity as their strict operational principle (efficient cause).

The American regime—such as we find it in 2020—was founded as a republic and contains the elements of the ”mixed regime.” The legislative branch is functionally republican, charged with the polity’s ontologically primary task of lawmaking. The legislature is the privileged branch of government because its domain—making law—supplies the substrate upon which the judiciary and executive operate.

This is why the legislature falls under Article One of our Constitution: it makes the laws that judges adjudge and Presidents enforce. The executive branch is in part functionally monarchical, charged with the king’s duty of executing extant law. The judiciary is of course aristocratic, charged with adjudging the Constitutional validity of extant law.

Arkes writes, “my late friend Antonin Scalia insisted that the Declaration had no standing in our [constitutional] law because it was never enacted [legislatively].” But ratification by the legislature is central to republican lawmaking. Per Arkes’s formulation, does the ontologically and chronologically primary branch—the branch making the laws to be adjudged or enforced—bear any fixed or formal equipoise as lawmaker? Without a means of parsing legitimate (legislative) from illegitimate (judicial) bodies of lawmaking, there is no basis for a republican form of government.

Whether Arkes fully affirms the position or not, Vermeule’s postliberal, anti-republican integralism, which would seemingly reject rule by the people, emerges recognizably once the legislature’s role is dismissed.

Originalists insist that, if the republican form of government is to persist, law must be made by legislatures and ajudged by judiciaries according to the original, public meaning of the Constitution (which can be licitly amended through one of two proper channels). And we must insist on our insistence.

Catholic Textualism in Action

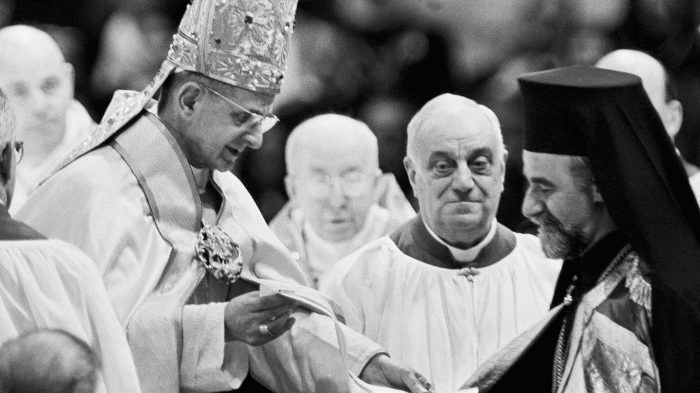

This divergence between the two competing forms of Originalism proves especially relevant in the curious case of the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), whose sacred constitutions threaten, in many progressive-sounding clauses, to contradict previous Catholic Tradition—which would rupture the Faith. Catholics who believe the Church was not vituperated by the revolutionary intent of Vatican Two’s leading periti became practical textualists in 1965 when the Council’s last constitution was ratified.

After all, the strong majority intent at the Council was, undeniably, radically progressive. The story is well-known even to most non-Catholics. Many revolutionary Council fathers authored the VC2 constitutions with what Monsignor Charles Pope calls “weaponized ambiguity,” constitutional text designed to be radicalized retroactively, as theory turned to practice in the immediate post-conciliar period.

We’ve all watched this catastrophe play out over fifty years. As Edward Schillebeeckx said of his contingent’s tactic: “we knew at the time how we would later interpret the [vaguely written] documents.”

In other words, the sacred constitutions of VC2 prescribed a poison pill of technically sound doctrine to be subsequently fashioned into unsound, unCatholic praxis. The question for Catholics like Vermeule, Arkes, and myself is: does the “real” meaning of Vatican Two reduce to its documents’ intent, or to their ambiguously revolutionary yet (mostly) innocuous original public meaning? Only textualism can capably explain how regardless of the abiding intent of the Council, the result of the actual constitutional documents need not be harmful.

Sacred VC2 constitutions make us think about what a constitution is: a multi-author document expressing the sovereign will of multiple ratifiers at a convention—in this case covenantal agents of the people of God. But a constitution’s meaning is not the vector sum of its authors and ratifiers: its meaning is the binding public signification of its words, as originally ratified. If a constitutional term’s meaning popularly changes a decade after ratification, the ten-year-old meaning of the term remains what was ratified (until formally amended). Ratified meaning is time-stamped and time-sealed.

It is conceivable—as happened at the Second Vatican Council—that a faction of revolutionary authors and ratifiers could embed their revolution within the vaguest clauses of the constitutions as a killswitch to be flipped at a later date. Since the goal of these revolutionaries was heteropraxy and not heterodoxy, little did they care that the (original, public) meaning of their suggestive byplay remained to posterity orthodox, as long as it was received and practiced as the opposite of orthopraxy.

Their benighted progeny two generations later wish that they had articulated the revolution clearly rather than reifying a protection for traditionalists: live by innuendo, die by innuendo. Even an author does not govern the public meaning of his immortalized and ratified constitutional text if it militates against his intent.

Since the close of the Council in 1965, excluding those who welcomed the progressive interpretation, Catholics have divided into two interpretive groups.

The first group, the rupturists, conclude that no continuity exists between the periods before and after VC2. They unknowingly employ the intentionalist jurisprudence, based on the radically progressive intent of the Council’s authorial leftists. Even as they bemoan it, this group runs afoul of the indefectibility of the Catholic Church by announcing the end of a bimillennial doctrinal era and the beginning of a new one. They toil on in dimness and in doubt, believing more or less that the Council constitutions ruptured the One True Faith.

The second group of Catholics (to which I belong) interpreting VC2 concludes that, notwithstanding ostensible tension presented by the Council constitutions, a textualist “hermeneutic of continuity” can counter-weaponize the original, public meaning of even the most troubling, vaguely-penned clauses of the constitutions. “Look at the original, public meaning of the constitutions’ words,” we say, “not the (bad) intents of many of the authors and ratifiers.”

Non-textualists look at VC2 constitutions like Dignitatem Humanae, Lumen Gentium, and Gaudium et Spes, and dejectedly conclude that Roman Catholic indefectibility has been forever broken.

A textualist view of the hermeneutic of continuity duly recognizes ostensible tensions between pre- and post-conciliar Church teaching, then dissolves or collapses that dichotomy by insisting that change cannot be made by mere innuendo: the original, public meaning of the sacred constitutions prevail.

The ruling on the football field (i.e., pre-conciliar tradition) stands unless sufficient evidence to overrule the call (i.e., explicit Conciliar text) has been clearly presented. Cases of opacity and uncertainty—such as unclear VC2 “updates”—must be “lined out” like an arguable challenge to a play-call that fails to meet sufficient evidence to overturn the standing call (i.e. tradition).

Textualism to the Rescue

Textualism presents the only way to embrace the modern, three-branch version of Thomas Aquinas’s “mixed regime”: the legislature makes law and the judiciary interprets it tightly. Textualism also presents the only way for a Catholic like myself or Vermeule or Arkes to continue to believe in the indefectibility of the Church after 1965: sacred conciliar constitutions mean something different from their Jacobinist authors’ intent.

So, why the academic fad of Originalism-bashing among Catholics and conservatives? The answer is simple: many of them reject republican regimes in principle and so they discredit the only jurisprudence—textualist Originalism—which duly serves and preserves it.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Too often, experts who are working to "save American democracy" are doing anything but.

Critical race theory was never designed to reveal truth—it was designed to achieve power.

Jack Smith’s indictments of Donald Trump are unconstitutional because he was already tried in the Senate.

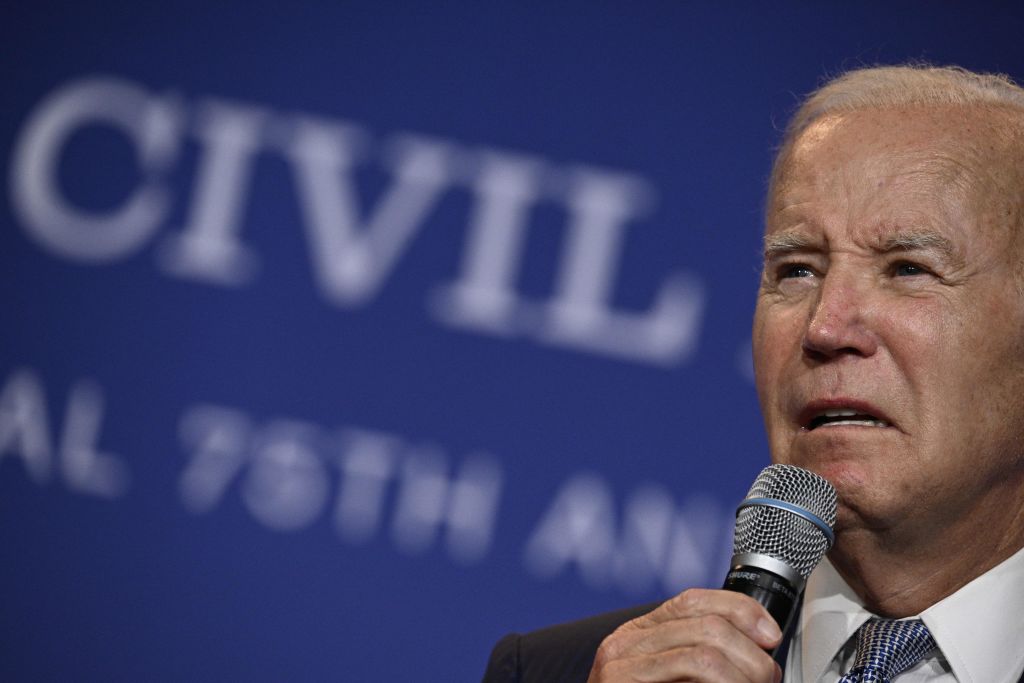

Despite the media’s subterfuge, Missouri v. Biden is a complete victory for the plaintiffs.

A half-measure whose time may have come.