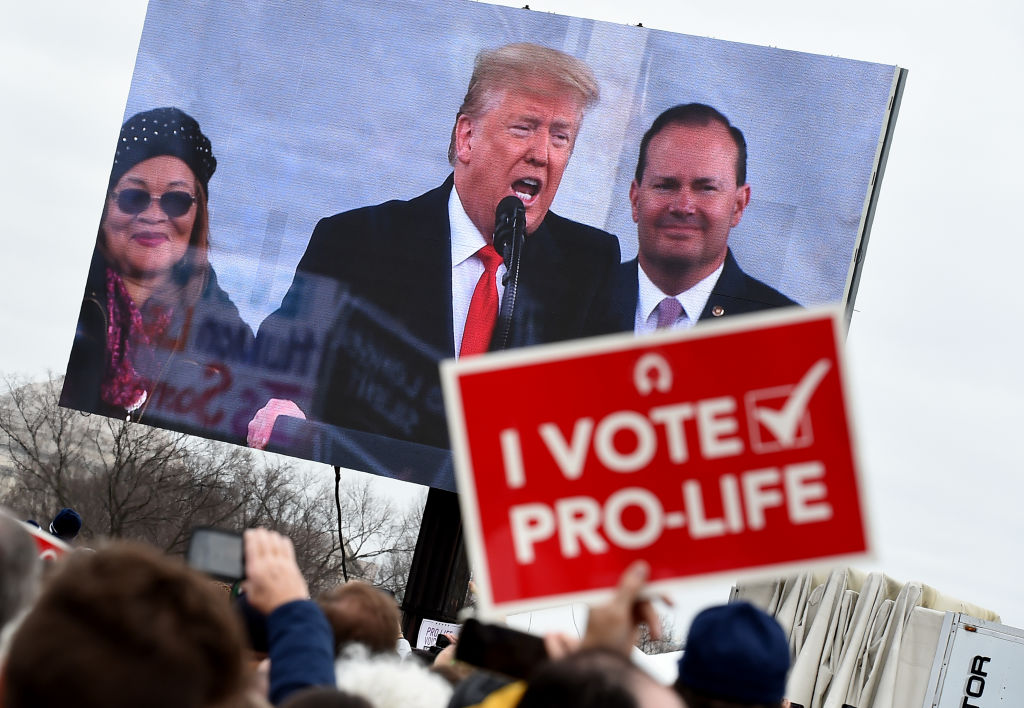

Pro-aborts will never forgive him for helping overturn Roe.

Can Conservatism Be Conserved?

When the war against wokeness is over, our common culture could be history.

It’s a phrase you use when you mean, ironically or sincerely, to make trouble: “Y’all ain’t ready to have that conversation.” On Twitter, it’s standard for announcing an uncomfortable discussion about a tricky social problem. “Everyone hates on Christians for opposing gay marriage,” for example, “when it’s Muslims who hate it most—but y’all ain’t ready to have that conversation.”

I wonder whether we’re ready to have the following conversation—and I swear, I don’t intend to make trouble. The digital, post-Trump era has both reworked the Right and sown in it a dangerously unspoken, deeply unresolved tension: though we agree that the woke Left must be defeated, we are quietly and profoundly at odds when it comes to social issues. It’s time to name this problem, face it, and head it off before it blows up—and takes all of us with it.

Strange Bedfellows

Deep down, almost everyone now accepts that our familiar political lines have been scrambled by the new world we’re in—one where the maelstrom of events and technology has churned once-fringe views right into the middle of the conversation. Shakespeare well understood the dynamic: “Misery,” he wrote in The Tempest, “acquaints a man with strange bedfellows.”

Twenty years of miseries on the Right have led to a new coalition, conservative in a true but transformed sense. Despite a palpable political backlash across the West—benefiting Republicans, Tories, and similar parties—the cultural catastrophes of our age roll on, from the “woke” turn against free speech to the “liberal” collapse of social cohesion.

In fact, right-of-center parties and leaders do not always represent the interests of the new conservative coalition. It’s not united by a political party but by a common cultural interest in preserving the freedoms of expression, association, and belief—without which our most basic institutions, and the precious goods they deliver, cannot be secured.

It is these freedoms which remain desperately under threat despite electoral victories by parties which profess support for them. British satirist Andrew Doyle observed this disconnect when he wrote that “In spite of the fact that we have a right-wing government, we should be in no doubt that woke politics is culturally dominant.”

By “woke politics,” of course, Doyle means the Western movement bent on ending the liberties that members of the new conservative coalition, like Doyle, are anxious to preserve. The reach and tempo of woke politics has shocked even moderate liberals. For many, the quintessential example is that it is now quite dangerous to insist that biological sex is observable at birth—that male and female ought not and cannot be conflated, no matter how strident the call for “recognition” of those who do so. Dr. David Mackereth, Julie Bindel, Jeff Younger, James Damore, and Julie Burchill are only a few of the many who have had their careers ruined or their families torn apart over this issue, sometimes by court order.

In light of these developments, more and more people at all levels of society have gone into political crisis mode, placing free speech at the top of their priority list and making common cause with absolutely anyone who will help them preserve it. One consequence has been the departure of such people from the Left and the Democratic party, where they no longer feel at home: hence the #WalkAway movement lead by Brandon Straka, the #Blexit movement led by Candace Owens, and the Intellectual Dark Web phenomenon led by pundits like Dave Rubin and Jordan Peterson.

If not all such people agree with Christopher Flannery that the Republican party is their only natural home, they at least agree with him that the modern Left has become intolerably antithetical to their most cherished principles and beliefs. The result of this is what Peter Boghossian has called “The Great Realignment,” a tectonic shifting of coalitional ground:

I am a non-intersectional, liberal atheist. If a conservative Christian believes Jesus walked on water—and believes this either is or is not true for everyone regardless of race or gender—and if she values discourse and adheres to basic rules of engagement, then she is closer to my worldview than an atheist who believes race and gender play a role in determining objective truth and that her opponents should not be allowed to air what she considers harmful views.

The rise of woke politics, and the urgent need to defeat it, has made strange bedfellows of all of us in the new conservative coalition.

Whose Conservatism?

This is why calling the new alliance “conservative” at all is at once intuitive and bizarre. It describes a group who really do want to “conserve” something: all are united in the effort to defend certain liberties which are essential to truly civilized Western life. What could be more conservative than defending and repairing the historically foundational elements of our societal structure?

On the other hand, many in this group might strenuously resist, or even reject, the label. Andrew Doyle, Peter Boghossian, Douglas Murray, Candace Owens, Jordan Peterson, Christopher Flannery, Brandon Straka, Julie Bindel, James Damore, Bret Weinstein, Julie Birchill, Blaire White: only some of these people would call themselves conservative—including some on the Right!

An inescapably important reason for this is that many members of the new conservative coalition (especially those who don’t identify as conservative) reject the label because they hold views, and practice ways of life, which the historic conservatism of only a generation ago deemed deeply distasteful, even unconscionable. Weinstein and Boghossian are atheists. Murray, Doyle, and Straka are openly gay. White is transgendered, and Birchill and Bindel are lifelong feminists. As recently as the ’90s, being conservative would pretty invariably have meant that you opposed gay marriage; in the ’60s it would have meant that you considered homosexuality a threat to the West’s deepest foundations. In the ’30s it would have meant that contraceptives and women in the workplace were likewise anathema.

Some present-day conservatives still believe these things, especially when it comes to homosexuality and transgenderism. But others are direct beneficiaries of the very social upheavals which so appalled traditional conservatives in the generations before ours. And so, depending on whom in the new coalition you ask, homosexuality, atheism, and women’s employment are either tolerable, acceptable, or fatally misjudged parts of our social order. When you think about it, this extent of disagreement about fundamentals among a group of people otherwise in firm political alignment is shocking.

But the realignment has happened because the weaponization of wokeness has inflicted an even greater shock. We in the new conservative movement have called something like a truce on the social issues that divide us because we are useful to one another in an urgent common cause.

There’s a certain practical wisdom to this. But it has a short fuse. Given the highly personal nature of the issues at stake, this is no surprise. Tempers flared when minister and podcaster Jesse Lee Peterson asserted there is “no such thing as a gay Christian or a gay conservative.” Spirited, often hostile discussions ensued as “socially liberal” conservative speakers faced the sarcastically crude question presented by “tradcaths” and “groypers” on the Right: “how does anal sex help us win the culture war?”

Other more elaborate and complex, but no less heated controversies have arisen periodically in the new conservative discourse—from the “Ahmari-French” debate, to the Catholic integralism question (with its attendant critiques of free market systems), to the dispute over whether to ban porn. Each of these episodes dramatized the profound disagreements that erupt from festering grievances.

And each led the various parties to smear one another as “libertarian,” “nihilist,” “Stalinist,” “degenerate,” or worse, the point of which was always “you do not really belong on my team.” Result? Our supposedly defining debates failed to deliver a resolution or a victor, melting into low-intensity conflict because we all faced defeat in a wider war. However understandable, this strategy, to put it somewhat ominously, cannot continue.

Can We Be Friends?

If the new conservative alliance is merely a marriage of convenience, then very well. “At all times the sincere friends of freedom have been rare,” wrote Lord Acton in his 1877 History of Freedom in Antiquity: perhaps what we are seeing now is merely a temporary strike force scraped together out of every willing and remotely able-bodied soldier, assembled only to answer the needs of this one urgent moment.

But if so then we must accept that when our present war is over we will have precious little in common. If today’s Great Realignment bespeaks only desperation and not a newfound brotherhood, then ultimately we do not share nearly as much as we think we share—and we will not continue to get along once woke politics is defeated.

It is my great hope that this is not so.

And in this case I believe I do have reason to hope. If we are in deep and tacit disagreement about how the freedoms of speech and association should be applied to particular cases, nevertheless we have discovered in our hour of need that we agree about their importance, even their centrality, to something called the West which has nurtured us all and which we all love dearly.

There must be a philosophically robust way to articulate what this “West” is, and why each of us in our many distinct modes of life have nevertheless come together to defend it. What is it? Why, at this late date, do we have to ask? Some important recent books—notably Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed in 2018 and Christopher Caldwell’s The Age of Entitlement this year—have argued that the West’s present social trauma is not a perversion of liberal reform but, in one way or another, an unavoidable consequence of it. Is this so? The power of the question lies in our sneaking suspicion that we are avoiding trying to answer it.

Our failure in this regard has motivated all of the painful moments in which we have turned on one another with astonishment and even disgust. It will continue to do so unless we are all ready to ask each other some difficult questions.

Socially liberal conservatives, for example, should think about the following: at the moment, the LGBTQ and feminist movements are behaving in a way that would seem to prove the very real existence of the much-mocked slippery slope. Back when we were debating whether to decriminalize homosexuality (for example) or when women were demanding the vote, there were those who said that doing so would open the door to a whole host of woes. It will not do to dismiss such people as hysterical alarmists: through their eyes, the present mania for things like transgender children and partial-birth abortion are proof that their fears were exactly correct.

Was this inevitable? If not, why not? What is the positive case for gay and transgender rights which stops short of madness not merely as a matter of taste, but as a matter of principle? Can atheism be permitted as a viable life choice without becoming the default option in America’s public schools and public square? If so, how and on what grounds?

More traditionalist conservatives, for their part, might consider what their actual aims are. It has become increasingly clear that the social justice movements of the ’60s and ’70s have spun wildly out of control. But is anyone really willing or able to reverse them entirely? Should people really be discouraged from even asking taboo questions “out of terror,” in the words of one commentator, “of social and legal sanctions”? If this seems extreme, what sort of tolerance are traditionalists willing to extend to people whose lifestyles break the mold of teleological, religious morality?

Perhaps in an alternate timeline we new conservatives—gay and straight, Catholic and atheist, liberal and traditionalist—would never have had reason to give one another the time of day. Without the common enemy of woke politics maybe these tough questions would not be ours to answer. But this is the timeline we got, and here we all are in the same room together. Either that is an unfortunate necessity of history or it is an act of the providence which makes good what was intended for evil.

My faith, my hope, and my intuition are that the latter is true. But if so, we must become ready to have that conversation.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The Dobbs ruling will determine the future of American conservatism.

As the Left abandons the meaningful existence of gender, abortion remains a sacrament reserved for women in the woke cathedral.

Confusion about the scope of Roe v. Wade besets even Republican senators.

The pro-abortion party tries to defend the practice by not talking about it.

A new era in American politics.