Part II: Honor and self-constraint can stave off tyranny.

Camp Vibes Make Soft Men

What I saw at Vibecamp.

This article is an observation about what’s happening to men.

It covers a mysterious event called Vibecamp, popular among the tech elite, that was held in June in rural Maryland. Lower in profile than its nearest analogue, the annual Burning Man festival, Vibecamp is probably also more revealing when it comes to a certain coterie of high-status but directionless males. I need to say clearly that this should not be read as a condemnation of Vibecamp or the people who participate in it. I spent less than 24 hours there before allowing myself to be led away.

Plenty of think pieces lament lowering sperm counts, estrogenic microplastics, loneliness statistics, suicide rates, and atrophying vitality in the dating sphere. “What’s the Matter With Men?” asks the New Yorker, “The Crisis of Men and Boys,” shouts the New York Times, “Men are Lost,” warns the Washington Post, “The Crisis Over American Men Is Really Code for Something Else,” informs Politico, all while doing their level best to excise and alienate actual men, or at least the ones who try to act like men.

Rarely is any reporting about men done on the ground. There are barely any straight male reporters left, and the few that remain are blindly left-wing, which is to say suspicious of and upset at boys being boys. We don’t actually see what alienated, porn-addicted, feminized men look like, or how exactly the angry high-T ones get excluded and undermined. To do so would give a face to a threat—rather like, God forbid, trying to understand other people’s wrongthink.

This sucks because the ’50s-’80s greatness period of American magazine reporting essentially amounted to a protracted exploration of masculinity by and about odd, unstable, and difficult men. It mapped to the same greatness period in American film. Mailer, Thompson, and Wolfe were the Coppola, Kubrick, and Friedkin of words, painting naked male aggression as an indispensable and inescapable primal force. Even the gay ones, e.g., Capote, reported back the authentic details, good or bad, in their juiciest and most honest form.

Today, all we’ve got are “the experts”—Ivy League diversity hires on Adderall—churning out think pieces based loosely on data gleaned from digital surveys whose participants have received $5 Amazon gift cards in exchange for sharing what it’s like to be a man.

This is not to say that I’m an example of manliness. In many ways, I’m more feminine than most of my cohort, even the apologetic progressive ones (and particularly the ultra-competitive gay ones). But that’s also why I can see this better than most. Because I started as soft as they come.

Besides physical weaknesses (extremely severe asthma) and beyond environmental factors (being the only child of ultra-progressive theater academics), gentleness and uncompetitiveness came to me naturally. As a child, I thought of myself as an angel. For Halloween one year, I asked my parents for an angel costume, which they of course eagerly obliged. I felt pure benevolence toward my fellow children. One of my earliest memories is sitting in the lap of the one black kid at my elite Chicago private school, a fat boy, and I felt overwhelmed by love and pity toward him. During theater class, I laid on the floor in a cross position and felt like the messiah. I told people I had ESP.

Over time the angel fell to earth, trampled as we all are by the unfairness of life. My parents moved us to Evanston and sent me to a public school. We lived on the poorer side of town, and nearly all my friends were black. At first I refused to fight, but over time I learned that memories of one’s own cowardice hurt more than bruises. Scales grew.

Later, I went to a college known for rich Jewish kids. I joined the harshest fraternity and slept on a floor covered with sticky beer and glass shards for seven straight days. I was mocked for theatrical mannerisms; the brothers called me “thespian.” The self-regard bled out. I learned to interpret my feelings of uniqueness as narcissism, and to hate them when I perceived them in others. I learned to turn off the tender worry and to allow pure molten fury to take over. The softness morphed, slowly and over many years, into hardness.

To our fat, weak, feminine world, the above will read as sad or tragic. Therapy speak has no word for “good trauma.” But I don’t see it that way. I see it as beautiful. Muscle grows from damage, not vice versa. Hardening the softness is what it means to grow up.

Bunny Boy

Middle seat, flight to BWI. Next to me at the window sits a 25-year-old man. He clutches a Nalgene and a stuffed white bunny. I eye him as we take off over gray skies. Blonde curls, glasses, perfect buccal fat; Timothy Chalamet gone wrong. Cluster B mother couldn’t discipline him, turned him into her stuffed animal, and so now he carries his own. Above the clouds, the sun is visible. I feel good for the first time in months. Bunny boy slams shut the window, pulls up the hood on his mauve designer hoodie, and tries to sleep.

I’m on the way to Vibecamp: Burning Man for nerds. There will be 800 of them, mostly men, and seemingly more transsexuals than women. The celebrity prostitute Aella will excite them on stage with frank counterfactuals about Hitler. There will be frank discussions about HBD (human bio-diversity), and frank attempts to fight, dance, and exercise. There will be horrible food. Mushroom chocolates and ketamine will be the weapons of the day.

Several hours later, I’m drinking G&Ts and sweating and tweeting about going to Vibecamp. Bunny boy has graciously retracted the window shade so I can stare down. The fractal arteries of the Mid-Atlantic spread out below, the trees like little green broccolis. I love this part of the country. There’s something American about it.

I arrive in Baltimore in the late afternoon. On the Vibecamp Discord, I’d been offered a ride to rural Maryland, where the event will take place, from a benevolent stranger and fellow attendee. I meet him at the baggage claim. Tall, good-looking, friendly face. Close to the platonic form of “handsome tech guy” that you might see in a Netflix show. Former FAANg engineer, former athlete, former achiever.

He’s part of TPOT. TPOT stands for This Part of Twitter, a designation covering the Rationalists and Effective Altruists who occupy the opposing horseshoe tong from the Dissident Right, a short but meaningful chasm between “people who care about others” and “people who care about beauty.” Effective Altruists believe in extreme utilitarianism and the duty to maximize the good. They love to consider abstract calculations about the utility of starving Africa versus your morning latte. They’re drenched in therapy speak and feminized expressivism.

We take an Uber to pick up the car, a Turo, which is like Airbnb for car rentals. He tells me he’s gotten into meditation/emotion type stuff, and has spent the past year in intense therapy. A year ago he took MDMA and had a bad experience. Came out of it anxious, couldn’t sleep, couldn’t quiet the brain for months. Went to a therapist and started having intense body memories of a buried trauma. With the therapist, he uncovered the memories, feeling them radiate through his body as they returned. This led him to TPOT, where tech people gush about their newfound emotions and how they finally managed to break down the barriers blocking them from real “felt feelings.” He says he spends his days exploring these new body emotions on Twitter, following accounts like Nick Camarrata. He says TPOT is very different from “Tech Twitter” from whence he came.

We Uber through Maryland. Having had a similar experience with MDMA abuse followed by months of latent anxiety, I relate to him quickly, which leads him to open up even more, although I’m realizing that “opening up” is the currency of Vibecamp. We’re both disgusted by people who think that knowing the rules is a skill. He says Mark Zuckerberg makes chess moves against people who don’t even know they’re playing. He used to be like this, he says, separated from others by the impetus toward constant competition and superficial achievement. Made him great at swimming, but not at happiness. He reiterates that before his breakdown he’d never felt emotions in his body, only in his mind—game victories feel best in the mind—but that’s just a tiny part of experience, and perhaps the least satisfying of all.

We find the Turo in a pretty little complex with multi-colored townhouses smushed together like slabs of ice cream. A pristine white Jeep sits there waiting for us, app-connected and ready to go. There’s a cute little park with a swing set and lush gorgeous green trees. We connect to the Jeep and drive it through Maryland. He says his parents are still grieving from the revelation of his repressed memories. “That bad?” I ask. “Yeah like the worst thing,” he says, “the worst possible thing.”

That was when I started feeling guilty about what I had, in my mind, come here to do: make fun of people going to Vibecamp.

Camp ChampaWampa

We acquire two more passengers: a well-dressed transsexual with a greasy German look, tight jeans, pointy platform boots, a leather jacket, and scraggly facial hair, and a gawky 19-year-old suburban Jewish neoreactionary who will later accompany us on our escape. We enter a giant Walmart for supplies, where I buy a bunch of glow sticks that I never use and a massive bottle of Maker’s Mark that I use all of. We’re about 20 minutes outside Baltimore. Poor black and white trash sparsely populate the cavernous store, all the white women with teeth sucking meth face and their stupid PG County accents. We take a shot of Maker’s in the parking lot.

Assuming the transsexual is a lefty/rationalist (he doesn’t really do much besides make occasional Gen Z noises and pop culture references), the group in the Jeep learns that we’re a perfectly divided foursome: two Vitalists (brainy post-right) two Rationalists (brainy post-left). The kid excitedly explains Yarvinism and I back him up, so the other two enter passive curiosity mode, retreating to short sighs of encouragement.

After about an hour’s drive, we pull up to a surprisingly manicured looking campground; a ring of colorful cabins around a long, downward-sloping green lawn. It looks like an idyllic teen summer sports camp, and I imagine that’s what the venue originally was. This is disappointing. Given that Burning Man occurs on an ultra-remote moon dust desert that takes 12+ hours of waiting in traffic to enter, and given the tech-elitist bent of Vibecamp, I thought we’d be in some exotic deep forest, perhaps inhabited by inbred mountain men or the Jersey Devil. Pulling right up to a clean parking lot outside of Camp ChampaWampa was not what I had expected.

The first thing I notice—beyond the clouds of awkward-looking tech people with weird bodies interspersed with occasional good-looking tech people with fit bodies—was an interracial couple in vaguely Indian dress under a blue shroud muttering some sort of mantra to each other. They matched the decor, which emanated SEO-friendly, deep-fried, witchy esoterica—a copy of a copy of a copy something someone saw once, like the plastic elf extension on a nerd-girl’s ear. Crudely drawn skulls, snakes over moons, old time western looking lamps—Vibecamp looks and smells like a Bless International™ Indian Hippie Bohemian Psychedelic Gold Blue Peacock Mandala Wall Hanging Bedding Tapestry, or perhaps a tekkit™ Sun and Moon Tapestry for Bedroom Aesthetic Wall Hanging Trippy Tapestry Boho Wall Decor Hippie Black Tapestries for Living Room Dorm, on the wall of a freshly-minted project manager straight out of Emerson College.

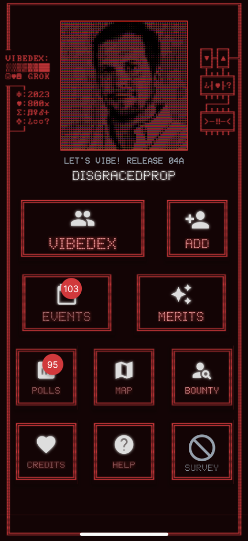

You meet people you’ve heard of from Twitter, and people have heard of you. Your clout depends mostly on two things: 1) how many Twitter followers you have, and 2) where you work (there are many FAANG employees—Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google). The Vibecamp organizers created an app that supposedly made this identity-status dance easier—Rationalists are always looking for digital lube to reduce the awkwardness of human interaction—but the app crashes constantly, so they tell people to look at each other’s lanyard badges or rely on Discord to find each other.

Strange that a gathering of gifted programmers would produce such an unusable app. Later I learn the cause. The primary original founder of Vibecamp, a straight white man, had recently been ejected from the group of organizers. His blonde female co-founder had staged a coup and exiled him for non-sexual misdeeds, the details of which I was never told. Not a #MeTooing but a sort of adjacent, softer thing; a very typical longhousing for those of us who notice these kinds of things. That he himself was an empathy-signaling emotionally-conscious loving being did not, of course, save him from swift removal from leadership of his own creation. The result, as always, is a lack of vision and clarity.

The Neoreactionary cabin: a ring of bunks in a room, all but one of them full of us thought criminals, one errant Googler stuck in the last bed in the corner, next to mine. In its defense, Vibecamp does not discriminate on ideological bases—Rationalists necessarily do not believe in censorship because it undermines the fullness of information (hence the frank discussions of Hitler and HBD). On the application to attend, there was an option to select “based” as an adjective to describe yourself. I have to imagine, however, that this also came from the exiled original founder.

And indeed, Vibecamp is therapyland. Every conversation gravitates toward how you’ve been hurt, how that hurt affects your performance, and how the other person’s trauma is similar to your trauma, and how crazy it is that you both have such similar trauma. It’s oppressive in its own right, but I will say it was preferable to the kinds of fearful, close-clipped conversations I’ve endured among normie tech elites in the green rooms of Comic-Con or VidCon or even at Burning Man itself. The Rationalists are, in their minds if not their souls, more correct than the mainstream.

My Inner Rage Helped Me

Basically, you rove around the green between your cabin and various vaguely-defined events, mostly variations on dancing, fighting, drinking, tea/Kava, meditation, and emotional awareness workshops. At night the events switch over to EDM rave parties.

This structure of rove-and-return roughly mimics Burning Man. Burning Man, however, builds its culture on the principle of radical self-reliance—meaning that there is no central authority, no one to feed you, no one to build anything for you. Everything you experience is peer-to-peer or self-supplied. At Vibecamp, there is a central dining lodge serving three square meals, snacks, coffee, and anything really you might need at any time. Despite attempts at decentralization, most events seemed to derive directly from the organizers (I myself submitted a proposal for a talk and never heard back about it one way or the other).

The DJ setups, held in big barn formats, seemed like lower-budget versions of standard festival fare. From what I saw they had lines, but then later were totally empty. I also saw lines for other places where people hung out, like the Kava Bar, the most popular nighttime destination, with over an hour wait. Burning Man has an occasional line, but, lacking a central authority and expanding on an almost endlessly blank moon-surface, you’re technically allowed to go wherever you want whenever you want. One place you can’t go, however, is the convenience store—no easy escape from the Playa, which makes for a much more compelling adventure. At Vibecamp, there was a WaWa about ten minutes away, where I ordered a tuna sandwich to avoid the appalling, Aramark-grade lodge food. Burning Man without the radical self-reliance, with lines, supervision, and centralized control, is essentially an adult summer camp, and it leaves one wondering what exactly is so unique about it in the first place, especially when it’s held in an actual summer camp.

In an adjacent cabin, I noticed that someone brought an entire Midea air conditioner. A man with cargo shorts and a chin strap gives me tequila, which I drink from a tin cup I’ve been instructed to bring to avoid waste. This is also a Burning Man trope, except the difference is at Burning Man your tin cup is essential because there are no trash cans, and thus no plastic cups; here there are trash cans and plastic cups everywhere. Our problematic (but notably popular) group wanders from one place to another—meeting acquaintances and being approached by fans. Someone comments on the effects of Ketamine. It’s an animal tranquilizer, meaning it tranquilizes the animal within. The perfect drug for our declawed era. I lose the group and bobble around. At around 1am, in a haze, I come across a fight. A ring of men and women stand in the grass around two wrestlers. Just as I join the circle, a man in a powder-blue dress defeats another man, causing him to tap out in submission. The man in the dress shouts “whoo whoo whoo!” and pumps his fist. He addresses the cheering crowd, “My inner rage helped me!”

There was an Aura Wash you were supposed to walk through upon entry and a bounce house that seemed to be in heavy use all the time. I avoided both. Tents dotted the landscape; there’s a camping option, cheaper than the cabins, which I’d say about half the attendees chose. Tents surrounded a pretty pond area like grease pimples around lips. The pond—hyperbolically called “The Lake”—also served as the “Hot Girl HIIT” workout location, which I did participate in, about 20 nerds led by a tall, woke, jiggly, and highly-energetic Kiwi girl who at one point said something like “those who experience bleeding” to describe the girls in the group. One exercise involved galloping like a horse to greet your neighbors. Halfway through, the air suddenly cooled and filled with the strong smell of petrichor, the sky turned black, and a thunderstorm began.

I ran out of the rain to the mobbed central lodge to fill my trusty metal cup, reeking of tequila, with coffee, which defeated the tequila in the olfactory battle. I sit with a friend at a table and force down the pale tasteless eggs while we’re crowded out by fat nerds. A beautiful rail-thin blonde in tight red leggings walks by us; we haven’t seen enough women, and we freeze and stare. But…there’s something wrong with her butt, and oh no oh no oh no she turns and it’s Macauley Culkin in his prime except with $1,500 lip injections and $15,000 hair: some poor Google engineer who gooned to sissy porn just one too many times. An image seared into my mind for life. The Tranny in Red.

I return to the cabin to find the sole Googler reading in bed. Fit and handsome, but boyish in a tight ringer T with a superhero or video game on it. He said, “Ugh, I just could not handle any neoreaction last night,” I assume referring to the conversations we’d had late into the night, the 9/10 problematic individuals that lay around him. I deflected by asking how he’d slept. “You need to just let the noise wash over you,” he explained, and that you got used to it, and that you eventually came to enjoy the comfort of fellow beings chirping around you as you attempt to sleep.

Abruptly, the word comes down on high that my neoreactionary cohort will be leaving Vibecamp early, as it has been decided that this place sucks and we’ll have more fun staging a moveable feast in D.C., where we can be around people like us. I resist at first, but then relent—I’ve learned to go with the flow in these instances, not against the tribe. In a few minutes we will rush up the hill back to the parking lot and blast Dixie while prematurely ejaculating ourselves from Vibecamp, 2:24pm in a three car deep caravan. “We just exited the Longhouse!” someone screams.

***

One of my favorite Bukowski poems is “The Genius of the Crowd.” It’s about how the people who preach the loudest about empathy are in fact the hardest, cruelest among us. It reminds me of my Vibecamp ride, the competitive Meta-employee swimmer who broke down and finally started feeling emotions.

“And the Best at Murder Are Those

Who Preach Against It.

And the Best at Hate Are Those

Who Preach LOVE

AND THE BEST AT WAR

–FINALLY–ARE THOSE WHO PREACH

PEACE.”

I love it because of course it affirms my worldview that progressives are the real oppressors, that they hate life, and that their ressentiment drives them toward phony empathy only toward people they can look down upon. But if I believe this I must also acknowledge its opposite: that those who are the best at peace are the ones who preach war. In other words, that the conflict-hungry vitalists of the Dissident Right are, in fact, more sensitive souls than the men of the Left.

And indeed, I believe this is so. We, like every outsider cultural movement—particularly the ones the Left identifies itself with—are sensitive men taking vengeance on a stale establishment that rejects us. Is this any better than ressentiment? Yes, because, by definition, natural growth means the strengthening of broken places. The reason why “opening up your emotions” will never be masculine is because the weakening of hardened tissues isn’t growth. It’s decay. It’s death. Your wounds don’t make you good, but your scars do make you strong.

Take it from the “thespian”: your weaknesses should embarrass you, not excite you. Being embarrassed of my inhaler was the best instinct I could’ve possessed—if I’d been proud of it, I would’ve never outgrown asthma. Never been able to chase the girl who later became my wife through a three day bender in Liverpool that involved sleeping in a cat-hair-filled closet for two hours a night. Never found out that I could control those things myself. Becoming a man means getting harder, more radically self-reliant. Most of the barriers you build are good ones. Erecting them is what it means to grow up.

On a plane on the way back, I sit next to two skinny, nerdy 20 something brunettes, a boy and a girl of almost identical pale, pimpled complexion, both with tight black masks on, the kind with additional inner white lining. They seem like they’re coming from Vibecamp, but I don’t know for sure. They don’t speak the entire flight. The second he sits down, the boy pulls out a Nintendo DS and starts playing, shoulders rigid, arms frozen at perfect right angles. He wears a black baseball cap that reads “Let the Fish Who Thinks He Knows No Fear Look Well Upon My Face,” an inside joke among fishermen and adopted by gamer nerds (it’s in a Mountain Goats song). He’s really clutching his DS, holding it awkwardly upright now, engrossed for hours. I wonder to myself, how long can he possibly hold the position without getting tired? Finally he slouches over, relaxes a bit, puts the game away. A relief—I relax too. Maybe he’s just ultra competitive, had to finish a level or something. But no. He reaches back down into his bag, digs around a bit, and pulls out his knitting.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

On campus, today's forlorn meritocrats no longer believe what the apparatchiks are teaching them.