It’s time to release the data that can exonerate police.

Broken Windows Redux

New York City’s return to “Broken Windows” policing is a window into the politics of public safety.

After 29 New Yorkers were shot in one weekend, the NYPD announced it would begin cracking down on less violent offenses that reduce the quality of life in more violent areas. This was the culmination of growing demands to do something to stop the increasing violence in the city. And in the wake of another gruesome attack this week—where a gunman shot at least 10 people in a subway car—those demands will only increase.

But Progressives wasted little time expressing their opposition. They dusted off an argument they’ve been making for decades, insisting that racial discrimination was the motivation for the crackdown.

“Make no mistake: these are stop-and-frisk units that will target Black and brown people,” said Bronx Defenders Managing Director of Impact Litigation Jenn Rolnick Borchetta. Similarly, Christopher Dunn, legal director for the New York Civil Liberties Union, concurred: “Locking up people caught drinking a beer in public or shoplifting food will only ensnare more Black and brown New Yorkers in a regressive and abusive criminal legal system—not address violent crime.”

Progressives’ condemnation of this necessary policy only feeds the perception that they’re soft on crime, a reputation the broader Democratic Party has been trying to shake.

For example, a recent report from center-left think tank Third Way pointed out that Red States have higher per capita murder rates than Blue States. The study didn’t try to establish causality, nor blame Republicans for increased crime rates, but it did try to undermine the dominant narrative about Democrats and crime. A cursory analysis of the Third Way report reveals that its authors tried to pull a sneaky trick by shifting the focus of the debate from cities to states. Of course, it is in Democrat-run urban centers where most murders happen.

This attempt is unlikely to move the needle, and not just because it’s so transparent. In the politics of public safety, the response to crime matters more than the existence of crime (and who presides over it) in shaping public opinion.

To begin with, we don’t really know what causes crime. We know it started rising in the sixties, fell for a couple decades after the mid-nineties, and is now rising again. The “why” evades us.

Progressives’ preferred explanation—the Root Causes Theory—suggests that social conditions like poverty cause crime, so alleviating poverty (e.g., with more generous government programs) will decrease it. Yet, as political scientist James Q. Wilson pointed out in 1975, crime increased drastically in the sixties just as economic opportunity was increasing and social barriers were decreasing, and when the federal government was ramping up spending on social services to unprecedented levels. Something doesn’t add up.

Crime is complex. But understanding why it occurs isn’t necessary to prevent it. Republicans tend to think of crime in rational terms. If you change the incentives to commit crime—that is, you punish it severely—then you should get less of it. However, more and more evidence suggests the best deterrent is not the severity of punishment, but the certainty of punishment.

A 2003 National Bureau of Economic Research report examined New York City’s dramatic crime decline in the nineties and found that “[t]he police measure that most consistently reduces crime is the arrest rate.” Similarly, a 2013 review of the criminology literature found that “putting more police officers on the street” had a “substantial deterrent effect on serious crime.” And, more recently, a 2021 study found that “shortening sentences overall but sending a larger fraction of offenders to prison can generate meaningful reductions in recidivism.”

But this requires both catching criminals in the first place and punishing them once they’re caught, which the U.S. is already imperfect at. According to Pew Research Center, fewer than half of all violent crimes are reported at all and, of those that are, fewer than half end in a prosecution.

Progressives should celebrate those statistics. They want less policing and empty prisons. They defund police budgets and refuse to prosecute certain crimes. If you were a criminal, would you like your chances better in a city run by progressives or conservatives? On the other hand, the minorities that Democrats claim to cherish so deeply are disproportionately the victims of the crimes they seek not to prosecute. What seems to evade the Democrats, however, is the idea that the best way to help victims is to prevent them from becoming victims in the first place.

As Princeton historian Julian Zelizer points out, “all Americans want to live in neighborhoods that are free from crime and danger.” Public safety is one of the foundational purposes of government. Unfortunately, only one side is serious about making it a reality.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

A chronicle of progressive mismanagement and rapid decline.

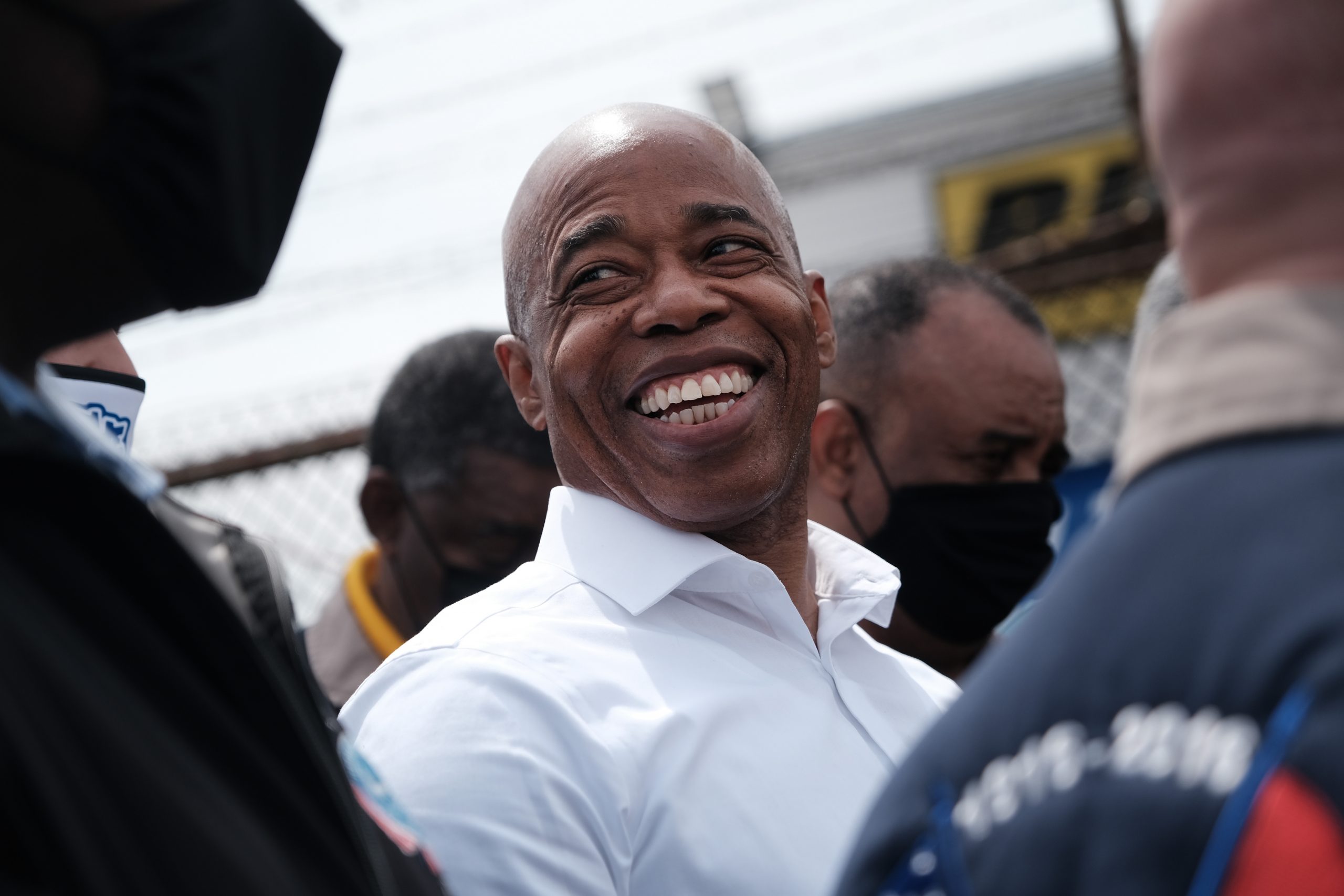

A closer look at Eric Adams’s odd history