How Hatred of History Hurts Us

Bill Barr Gives a Speech

Appraising Attorney General Barr and his critics.

Tom Stoppard remarked in one of his plays (Jumpers) that at a certain point, the moralist—the one who takes moral truths seriously—is likely to sound like “a crank haranguing the bus queue with the demented certitude of one possessed of privileged information.” Bill Barr delivered a speech on religious freedom at the law school at Notre Dame. Anyone who was tutored in American history and law, anyone whose education had encompassed a reading of the classics in political philosophy, would have recognized a speech drawing deeply on some of the best things said and done in the tradition running back to Athens as well as Jerusalem.

But none of that seemed to be noticed by some of the critics who quickly railed against Barr and his speech. They offered caricatures of denigration quite out of scale, unmeasured—and unmeasured precisely as they were untethered from anything that could confirm the pretensions of the critics to a lofty perch of learning.

The Mythology of Liberalism: Jeffrey Toobin’s Fake History

And so Jeffery Toobin, writing in the New Yorker, vouchsafed at once that William Barr had given “the worst speech by an Attorney General of the United States in modern history…[h]istorically illiterate, morally obtuse, and willfully misleading.” And where was that historical illiteracy shown at once to clinch the case? “In a potted history of the founding of the Republic,” according to Toobin, “Barr said, ‘In the Framers’ view, free government was only suitable and sustainable for a religious people—a people who recognized that there was a transcendent moral order.'”

“Not so,” said Toobin. “The Framers believed,” he said, “that free government was suitable for believers and nonbelievers alike. As Justice Hugo Black put it in 1961, ‘Neither a State nor the Federal Government can constitutionally force a person to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion. Neither can constitutionally pass laws or impose requirements which aid all religions as against nonbelievers, and neither can aid those religions based on a belief in the existence of God as against those religions founded on different beliefs.’”

Anyone with pretensions to scholarship in law or American history would have recognized at once that the lines Toobin attributes to Barr were the lines of John Adams. The tutored writer would have recognized them at once even if Barr himself had not been citing Adams as the source of that commentary.

And in the understanding of a “transcendent moral order” behind the law, Adams was clearly not alone; he was expressing the understanding shared widely among the ablest political men of that generation. James Wilson made the same point when he argued, contrary to Blackstone, that the American law could indeed contain a “principle of revolution,” because the American law began with the recognition of an unjust law—that a measure passed with all of the trappings of legal procedure could nevertheless be wanting in the very substance of justice.

Which is to say, America began with a recognition of a body of natural law, principles of moral judgment that were there before the positive law; and they would be there as a source of measuring the validity, or the moral justification, for those laws. Clearly, Alexander Hamilton touched the same understanding when he argued, contra Hobbes, that all morality cannot be merely conventional. Hobbes had neglected, he wrote, the presence of that “superintending principle,” the author of the moral law, along with the other laws of nature. It was that “deity,” he said who “has constituted an eternal and immutable law, which is, indispensably, obligatory upon all mankind, prior to any human institution whatever.”

But for Toobin, the avowals and the serious writing of Adams, Wilson, and Hamilton somehow do not count in revealing the true understanding of the Founders and the regime they had brought forth.

The truth of that regime was to be found, rather, in Hugo Black, FDR’s first appointment to the Supreme Court, a man bitterly hostile to the Catholic Church, and a former member of the Ku Klux Klan. It was Black who managed to place our jurisprudence of the Establishment clause in a strikingly different cast in 1947, in the famous Everson case. And there, Black showed the sleight of hand of a practiced illusionist. As he sought to sum up the tradition of the American law, he noted that “neither a State nor the federal government can set up a church.” True enough. But then he moved across the line into doctrines radically new: “No tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities at institutions, whatever they may be called, or whatever form they may adopt to teach or practice religion.”

That declaration began the move that would acquire more and more momentum, to drive religion out of the public square altogether.

It was one thing to say that the government may not impose religions by force of law, intervene in disputes on doctrine, or make appointments to ecclesial bodies, naming bishops and other prelates. But that was quite another from saying that the government may not recognize the salutary place of religion as a moral force for our people. Or that it may not take decisive steps to favor religion over irreligion.

Thomas Jefferson, when he was President, would attend Christian services taking place in the Capitol itself, in the hall of the House of Representatives. And he would ask Congress to provide aid to the Kaskaskia Indians in order to support their Catholic priest. What Toobin offers as his authoritative account of the history of the American law and the jurisprudence of religion is but a fable, a retelling and falsification of history, to suit the current worldview of the Left. It bears on the historical record with the same accuracy as Mel Brooks’s History of the World, Part I.

Religious Tolerance is Founded on True Religion & Natural Law

Toobin is done one better, in that department, by Michael Sean Winters in The National Catholic Reporter, who pronounces Barr, from his lectern, as “ridiculously stupid.” He offers as a rival thesis that religious freedom was not widely respected and protected, and he takes as a key point that “the Bill of Rights was not applied to the states until the adoption of the 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, and, in the case of religious liberty, the relevant clauses of the First Amendment were not applied to state and local government until the 1947 Supreme Court decision in Everson v. Board of Education of the Township of Ewing.”

Winters tees up his point to expose Barr’s constitutional ignorance, and then tellingly gets it wrong. If he had studied the cases on law, he would have known that the 14th amendment was extended to “incorporate” the free exercise of religion, not in 1947, but in 1940, with Cantwell v. Connecticut. It is more than revealing that Winters would not only make a mistake on an elementary point, but that he would identify the new, grand protection of religion with the case crafted by Hugo Black—the case that was aimed to put the respect for religion in our law in the course of ultimate extinction.

Winters did raise an enduringly apt question, though, about the tendency, even among the defenders of religion, to provide only a “utilitarian” account of the good of religion. We think of George Washington’s famous line: “Where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths which are the instruments of investigation in courts of justice?” And yet, if Winters had read Barr’s speech with any care, he would have seen the hand of a writer who had evidently been touched by the classics in political philosophy.

There was something notably Platonic in Barr’s remark that it is just “another form of tyranny—where the individual is enslaved by his appetites.” Plato offered to us that the man with self-control had a constitutional ruler in himself. He would forego to himself the right to do wrongful things, and in that forbearance he would become a stronger, not a weaker man. For he could concentrate his powers now on the things rightful for him to do.

What was engaged here for William Barr, as it was for the Founders, was the enduring difference between freedom and license. Engaged in any occasion of freedom was the question of whether that freedom would be directed to ends that were rightful or wrongful. Barr saw the Judeo-Christian teaching as bearing moral lessons that were quite convergent with the teachings of natural law, and the natural law could be known across the religious division, by Catholics and Baptists, and even atheists.

It took no revelation on the part of Barr to know that a country grounded in the Judeo-Christian ethic would offer tolerance and respect even for those of novel and exotic religions, as long as they accorded with the moral system that could command the respect of all because it could be understood by all. It delivered no news to Barr to point out, as Winters did, that the Mormons and other religions have been repressed at different times in this country—as when Jews were barred from voting or holding office in Rhode Island. But it seemed to run beyond Winters’s wit that none of that could efface the truth of those principles Barr was stating anew. Nor could it dislodge the dominant record of religious freedom that those principles managed to sustain.

It was not a “utilitarian” view of religion that Barr was putting forth when he recalled James Madison, writing to explain the Remonstrance against religious assessments in Virginia. By religion, Madison said, he meant “a duty towards the Creator,” and a “duty…precedent both in order of time and degree of obligation, to the claims of Civil Society.” Clearly, religion marked foremost for Madison the moral law that emanated from God, the moral order that was antecedent to all positive laws.

The teaching, then, was that the life of this republic began with people who had cultivated already a willingness to respect a law that ran beyond their own will and their appetites. Surely, there could be no deeper teaching about the salutary force of religion at the Founding—and even more urgently in our own day.

The Crisis is as Real as Our Moral Passions

But it was precisely that sense of urgency, sounded by Barr, that elicited the most mocking derision from his critics. “I think we all recognize,” he wrote, “that over the past 50 years religion has been under increasing attack”—that there has been a “comprehensive effort to drive it from the public square.”

It is 25 years since Fr. Richard Neuhaus sounded the alarm with his book The Naked Public Square, for the Establishment Clause was being revved up ever more to stamp religion as illegitimate in the schools or in almost any other public setting. One would hardly think there was any serious controversy on that point, and yet Barr’s critics treat it as a fantasy of Barr’s own making, along with his observation that the “militant secularists today do not have a live and let live spirit—they are not content to leave religious people alone to practice their faith. Instead, they seem to take a delight in compelling people to violate their conscience.”

Is that point really under serious doubt by anyone who has been paying attention of late?

Even the libertarians who favor same-sex marriage have pointed out that there is no need to prosecute bakers or florists who decline to engage their arts in celebrating that form of marriage. For there are many other bakers and florists more than willing to have the business. What delivers the surprise to the libertarians is that the activists are driven by nothing less than the “logic of morals” itself—that what is rightful should be pursued and promoted, and what is wrongful should be avoided or even punished. The gay activists are powerfully driven to insist on the moral rightness of their position. Those who would deny it are clearly stamped as wrongdoers who should be condemned and punished.

There should be no surprise in any quarter on this point. Lincoln noted the same logic at work in the crisis of his time, with the defenders of slavery: “Holding, as they do, that slavery is morally right, and socially elevating, they cannot cease to demand a full national recognition of it, as a legal right, and a social blessing. Nor can we justifiably withhold this, on any ground save our conviction that slavery is wrong.” And similarly, in our own day, the matter turns solely on our judgment on the rightness or wrongness of same-sex marriage.

For Barr’s critics to express incredulity on this point, belying their own moral convictions, is to offer either self-blindness or a partisan refusal to acknowledge any truth at odds with one’s political needs at the moment.

Mark Rienzi, that gifted lawyer and professor, aptly observed that if the government truly had a “compelling interest” in diffusing contraceptives through the country, the Little Sisters of the Poor would hardly stand out as a vehicle of prime value. An Obama Administration that sought to impose that obligation on the Little Sisters was obviously not driven by public needs. It was animated rather by the moral passion to impose this new measure of justice on the Church that has offered the main, enduring refusal to endorse this new moral order of things.

But in the same way, Jeffrey Toobin sees no moral shadings here: The refusal of tradesmen to become complicit in a same-sex marriage is something he treats as simply a matter of rank “discrimination.” Is he really unaware that serious people for generations have not thought homosexual marriage plausible, let alone morally defensible and urgent? Is he unaware that even the leading liberals in this country professed their opposition to that novelty right up the edge of the Supreme Court installing that form of marriage in our laws?

And yet, Toobin treats the opponents of same-sex marriage, abortion, and transgenderism as not merely malicious but as too backward to grasp what should be morally obvious. In a life spent studying law and given over to punditry, can he really be so distant from the vast traditions of thought and searching arguments on the part of minds far better than his own? Or has brute, unvarnished ideology just come into play once again to erase any sense of nuance or moral argument?

We’ve recently lost our dear friend, Michael Uhlmann, wise in counsel, gifted in teaching, and one of his enduring lessons for us is “Uhlmann’s Law,” which reduces to this: There may be no need to expend your wit in pondering theories ever more clever to explain arguments as unaccountable as they are implausible when stupidity alone—simple, old-fashioned, unalloyed stupidity—may be quite enough.

The Right Needs to Heed Barr’s Message

But it would be odd—and it would belie the artistry of Bill Barr—if we failed to note that he was delivering his speech at a law school, and a University, that was no longer prepared to receive, with a sympathetic understanding, the appeal he was making. Barr was making the case anew for the law that stood before the positive law, but he was willing to give it, in public, its proper name. That “transcendent moral order which flows from God’s eternal law” is “the natural law.” And it is “impressed upon, and reflected in, all created things.”

Twenty-seven years ago, when Bill Barr was Attorney General, I heard him deliver a speech of the same tenor and substance, in a Catholic meeting, and his talk was published later as “The Moral Culture: the Best Possible Life” (Providence, 1992). That may be quite enough to show that the principles and the lines of argument do not spring from any speech writer, but from his own serious reflections, cultivated over many years.

But there is no small irony in the fact that in conservative circles, the fashion long settled has been to mock and dismiss the natural law as a set of hazy principles hovering in the sky, with little practical bearing on our law. The Federalist Society has become the principal engine for scouting and shaping candidates for judgeships in a conservative administration. I have been a member and loyal supporter of that Society since its beginning. But it’s also true that the main current of opinion in that venerable organization is one that echoes the dubiety about natural law that was expressed by my own dear friends, Robert Bork and Antonin Scalia. And that sense of things is well reflected among the young conservatives who have found a congenial home in that rare family that has become the law school of Notre Dame.

Hence the challenge for Bill Barr. He has been enduring in making the case for the natural law, but now he finds the need to make that case ever more within the circles of his most committed friends. Bill Barr understood that his speech was part of his mission of recovering truths long fading from the public understanding. He knows that there has been a falling away from those truths even in the circles of conservatives.

He knows that the task he had set for himself long ago has become now ever harder.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Young women looking for meaning are enchanted by a new paganism elevating ego and material desire.

The presidential candidate stands against the Left's attacks on the ties that bind.

Rejecting organized religion doesn't mean rejecting religion itself.

An examination of the priestly caste of the leftist religions.

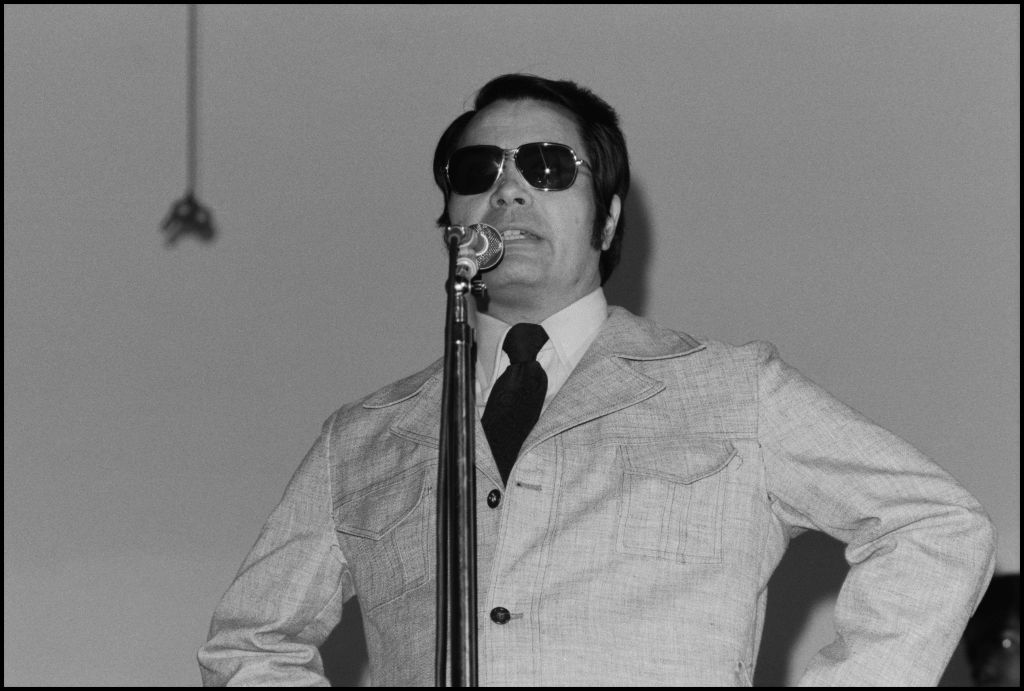

San Francisco's Democratic government propped up the infamous cult leader Jim Jones.