Trump has authority to act, and he should.

Be It Resolved

President Biden’s Covid workplace mandate revives an ancient debate.

Recent political developments have brought clarity regarding the goals of the regime. Biden, in his continuing dedication to “keep us safe,” has directed the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to enforce a rule mandating vaccinations by January 4 on employees of business with more than 100 workers, or else those businesses will face exorbitant fines.

Unsurprisingly, major wokeist corporations have cheered Biden’s attempt to seize authoritarian powers. Ford enthusiastically embraced Biden’s directive and wants its 32,000 employees to get vaxxed by December 8.Expect more of this whether the mandate is reversed in the courts or not. Corporate America largely has the same priorities as the regime.

When the Biden vax mandate was first raised, approximately 22 state governors responded that they would not comply, or planned to seek a court remedy. They have vowed to oppose mandates. Despite assurances from experts who have scarcely been right about the virus and its vaccine, the administrative state is trying to get ahead of what appears now to be the “pandemic of the vaxxed.” There is mounting evidence that the vaccine only works imperfectly, and that those who have contracted the bug without subjecting themselves to the stab are more immune to its effects and its variants.

It is apposite to pick up the thread that Glenn Ellmers raised some months ago in these pages, writing about how the states could provide a reasonable defense of liberty. Ellmers mentions the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions as representing a sophisticated political path to resisting the encroachments of the national government. His essay ends with a consideration that the states may form a reasonable bulwark against government abuses, while steering well clear of secession.

In the Resolutions, the “warm attachment” to the Constitution necessitated a response to an unjust law. It was in response to the love for the Union, and its perpetuity, that the Resolutions were adopted after deliberative modification through the legislative process. It is alarming to the careless reader that these Resolutions claim “the states, who are parties thereto, have the right, and are duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights, and liberties appertaining to them [Virginia].” Further, the “certain and definite powers” of the government did not make it “the exclusive or final judge of the extent of powers delegated to itself [Kentucky].”

The Resolutions object to the contravening of rights—due process of law, the assuming the powers of the executive, legislative, and judging into the one office, or one man. To put it into context, this is what Biden’s mandate effectively does. It casts aspersion upon the people and effectively prevents them from their livelihood. Kentucky’s Resolution states in this regard that, “the powers of self-government” are not to be transferred “to a general and consolidated government, without regard to the special obligations and reservations solemnly agreed to in the compact.”

Federalist 26 noted that the state governments had a constitutional role to play: “the State legislatures, who will always be not only vigilant but suspicious and jealous guardians of the rights of the citizens against encroachments of the federal government, will constantly have their attention awake to the conduct of the national rulers, and will be ready enough, if anything improper appears, to sound the alarm to the people, and not only be the voice, but if necessary the arm of their discontent.”

Madison admits that efforts to subvert the “liberties” of the “people” take time to be recognized. The states and the national government are in fact “different agents and trustees of the people” (Federalist 46). Madison continues to contend that federal encroachment upon the States would in effect send an alarm and would represent an “extremity.” However, the “State governments, with the people on their side would be able to repel the danger.” This remedy should occur after a “long train of insidious measures.” Madison confidently concludes that, “schemes of usurpation would be easily defeated by the State governments, who will be supported by the people,” and that “individual States as they are indispensably necessary to accomplish the purposes of the Union,” would have a salutary effect in halting such abuses.

Whether in the Resolutions, or in the Federalist, the aim of the states in opposing an unconstitutional order or law is based not on some unnatural conception of duly granted rights, but on the nature of the Union itself. That is, the objection to government abuses was always based on the defense of natural rights that the government might attempt to circumvent. These objections were not based on mere preferences against policies. They were meant as a “rightful” defense of the fundamental law Nature.

In his Report to the Virginia Assembly, Madison explains that the language employed in the Resolutions was meant to invoke the “people composing those political societies, in their highest sovereign capacity.” The people, then, are not lost in the state they reside in; in fact, they are the foundation of it. The objection to government abuse, was passed through the mass of the people—whether a majority or minority—to their respective states. The people, represented in their states, are parties to the Constitution. The “object” of their “interposition” is founded upon the “rights and liberties” partly stated in the Constitution, and then communicated through their states. This “fundamental principle” is set upon that, “which our independence was itself declared.” So dedicated to this most serious and solemn reason for political action that Madison crafted the opening preamble of the Virginia Resolution shading the opening lines of the Declaration itself!

Madison also dispenses with the notion that the Supreme Court has the final opinion on anything. He makes it clear that the other branches, as well as the people themselves have a say in what is and is not acceptable legal interpretation of the law. At its foundation, the “rights of the people [should be] secured against legislative and executive ambition.” The reasonable sovereignty of the people are best able to secure their own liberty.

We must dispense with the notion at this point that either resolution was a precursor to secession. Far from it. In his essay “Partly Federal, Partly National,” Harry Jaffa makes a convincing argument through James Madison that such was not the case. Madison himself denied that the southern notion of interposition and the Resolutions were in any way connected.

Jefferson and Madison, no less than Jaffa himself, made clear that no one state may nullify a law emanating from the national government. The response to the intolerable sophism of Calhoun and South Carolina during the nullification crisis, no less than the resolution of the Civil War, has gone to the opposite extreme—that no state may at any time resist unjust laws and acts of the consolidated government. This doctrine, as destructive to republicanism as nullification, in effect destroys federalism.

The Biden administration made it clear that the President will “run over” the states and the people if they do not comply with his mandate. However, to expect “unlimited submission is characteristic only of despotism.” In this, the occupants of the White House share a critical feature with the nullifiers of the 1830s. Both have the shared characteristic of severing the connection between human equality and the consent of the governed.

In the nature of the compact of this Union, whereby each citizen makes a covenant with every other citizen (the whole people), should Biden interpose his will, he is likely to throw open the doors to anarchy. The mass of the people, whether a majority or minority, have a duty to defend the Union against Biden’s attempt to assume in his hands all tripartite powers. The resistance of the states today is no different in spirit from the resistance to the British Crown before the Revolution.

The Resolutions received much criticism from sister states at the time, but the result of the deliberation that resulted turned into a decisive republican victory in the 1800 elections. The Resolutions did not amass numerous negative objections to government policy like we are seeing presently over the mandates. Madison anticipated that prudence may dictate pending the gravity of the situation a resistance to over-reaching government action. He wrote in Federalist 51 that the nature of the compact was divided between the national and federal governments. In this situation, the states’ opposition represents a “general alarm” where “government [espouses] a common cause” thus encouraging a “correspondence [to be] opened.”

Undaunted by the criticisms of the national government and supporting states, Kentucky passed a second resolution in 1799, concluding that “it would consider a silent acquiescence as highly criminal: That although this commonwealth as a party to the federal compact; will bow to the laws of the Union, yet it does at the same time declare, that it will not now, nor ever hereafter, cease to oppose in a constitutional manner, every attempt from what quarter soever offered, to violate that compact.”

The states (and, through them, the people) have a duty to interpose their persuasive opinion and employ all lawful means in protest.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

A look at the data

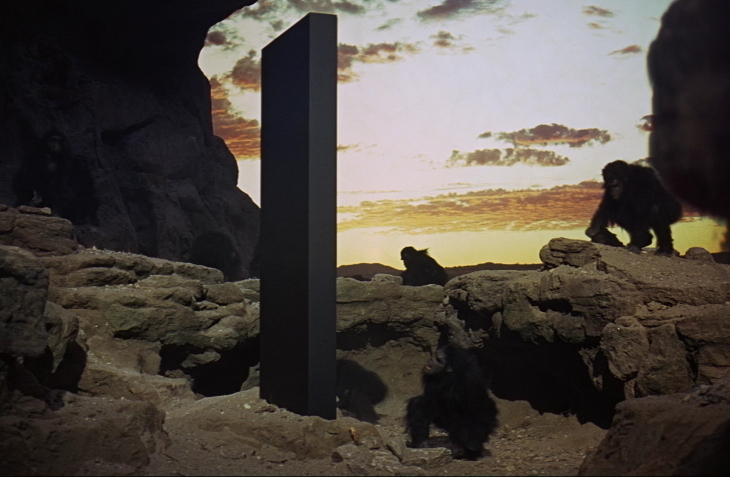

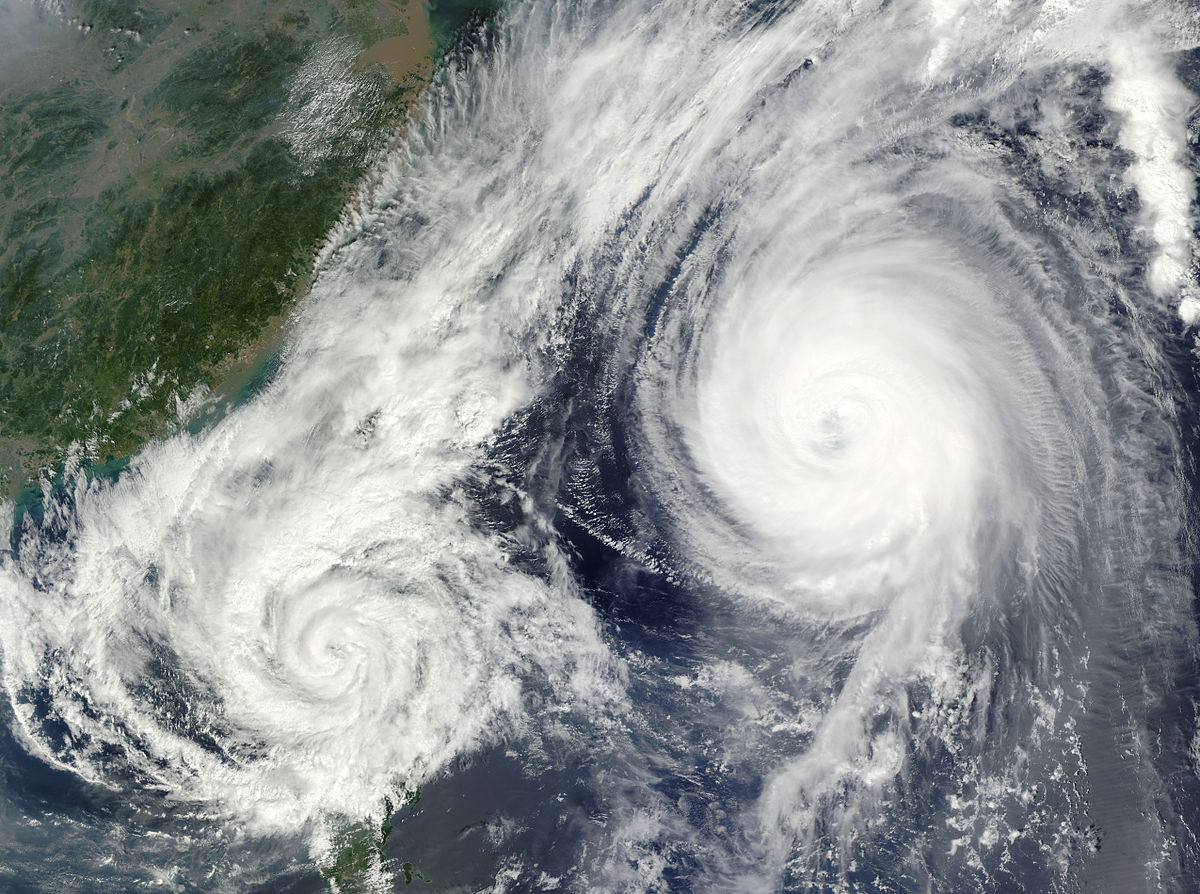

Two stormfronts are on a collision course over America. Where will it end?