What new ways of thinking about the body have in common, and how we can use them for the common good.

A Rose on Lincoln’s Grave

To reign as heavyweight champion in those years was to wear the crown of manhood before the whole world.

Sports fairly practiced—especially individual sports—are a great meritocracy revealing, for all the world to see, the beauty of excellence. In American history, sports have also been an arena for the working out of the great American principle of “liberty to all.” Only by living up to this principle, which is the world-transforming standard America chose for itself from the beginning, is it possible for sports or any other pursuit to take a just measure of human greatness. Abraham Lincoln thought this principle of justice—our “apple of gold”—was America’s greatest treasure and greatest gift. He called it “a standard maxim for free society, which should be familiar to all, and revered by all—constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere.”

This is why Americans celebrate Jackie Robinson’s historic breaking of the color barrier in baseball. And this is why we celebrate the historic achievements of another great athlete who came before Robinson and helped pave the way for him. In the words of Frank Bolden, who covered both men for the widely read black weekly, the Pittsburgh Courier, “Jackie played for the Brooklyn Dodgers, . . . Joe Louis played for the world.”

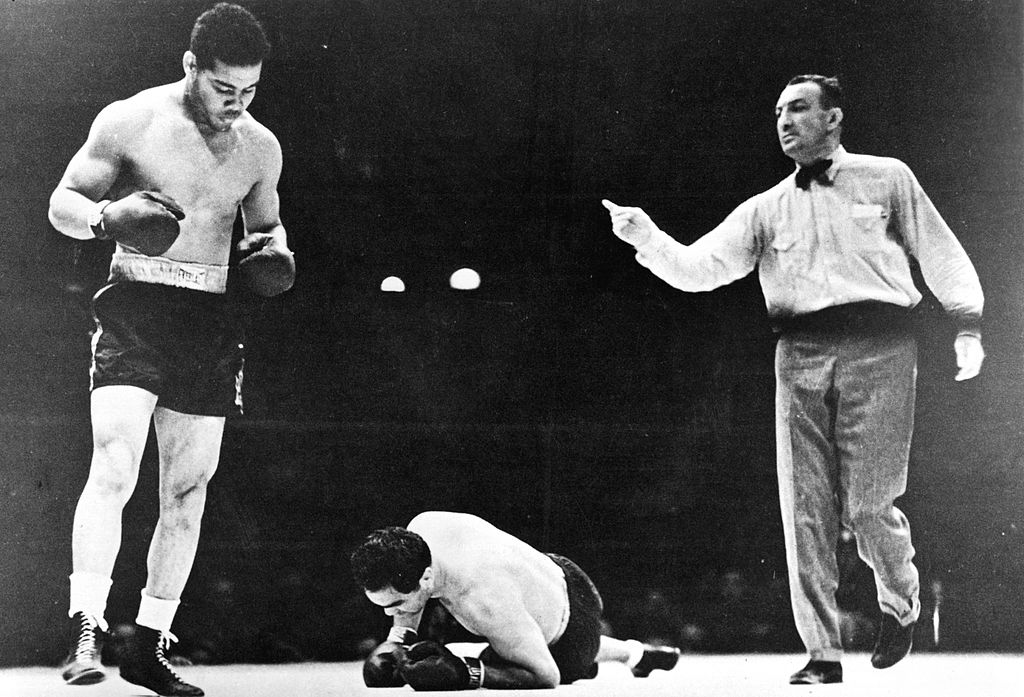

Louis was born Joe Louis Barrow in segregated Alabama and spent his early years in Detroit. His grandparents were former slaves. His mother, who was part Cherokee, tried to get Joe interested in playing the violin, but he spent his violin lesson money on boxing lessons. In the course of over fifty amateur bouts, Louis made himself into an immensely skilled fighter, with a thunderous right hand. He turned pro in 1934, and by 1936, nicknamed the Brown Bomber, he was undefeated in 24 professional bouts, 21 of them knockouts, and expected soon to challenge the current world heavyweight champion, James J. Braddock, the “Cinderella Man.” To reign as heavyweight champion in those years was to wear the crown of manhood before the whole world. Black Americans cheered Louis on as their hero, not just because of his thrilling greatness as a fighter, but because his greatness cast in a true light the injustice of segregation and Jim Crow. Already Louis’s greatness had drawn millions of white Americans to join their black neighbors in rooting for him. Now history would give his greatness added meaning.

The last steppingstone to a fight for the heavyweight crown was a bout against German former champion Max Schmeling. Schmeling himself was no Nazi, but Germany had been governed for the past few years by Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party, whose tyrannical rule and global ambition was based on the claim of white Aryan supremacy over lesser races, particularly Jews—and blacks. These international and political realities added their own significance to the fight, which was scheduled to be held in Yankee Stadium in June, 1936. Louis, by his own later admission, did not take Schmeling seriously and trained lazily. Schmeling took the fight with deadly seriousness, studied film of Louis fights in preparation, and controlled the fight from the opening bell, knocking Louis down in the fourth round for the first time in his professional career, then knocking him out in the twelfth—his first professional defeat.

For American boxing fans it was a great letdown. For black Americans it was devastating. For Hitler, it was glorious. Goebbels’ Nazi propaganda machine made the most of it. Boxing was combat, the ultimate test of race, and combat on a larger scale was coming. American democracy was decadent, ruled by Jews like Franklin “Rosenfeld” and contaminated by blacks like Joe Louis; Nazi Germany and the master race would prevail.

The more Americans heard this kind of propaganda, the more Joe Louis became the hero not just of black Americans but of all Americans. In 1937, Louis knocked out Braddock and won the world championship. But he wouldn’t feel the title was fully his until he was given a chance to fight Schmeling again, which he did on June 22, 1938, in a fight billed internationally as “The Fight of the Century,” pitting German Nazism against American democracy. It was headline news from New York to Berlin to Tokyo. The fight took place in a sold-out Yankee Stadium with over 70,000 in attendance.

In these years newspapers mattered, and Joe Louis got more column inches of ink in the newspapers than the President of the United States. A few weeks before the match, FDR invited Louis to the White House. The Germans had recently annexed Austria and were threatening war with Czechoslovakia. The New York Times quoted Roosevelt as telling Louis, “Joe, we need muscles like yours to beat Germany.” In his 1976 autobiography, Louis wrote about the upcoming fight that “the whole damned country was depending on me.”

As the fight began, the streets of Harlem emptied; black fans huddled around their radios, as did tens of millions of listeners around the world. In Germany, Hitler lifted the nationwide 3:00 AM curfew so that cafés and bars could carry the broadcast. As one indication of the political edge on the fight, 10 percent of the purse was pledged to Jewish relief agencies. Joe Louis’s greatness was vindicating the American principle of “liberty for all” not just in America but to “people of all colors everywhere.”

This time, he had no intention of letting Schmeling control the pace of the fight. He attacked furiously from the start, pounding Schmeling with crushing lefts and rights. Two minutes and four seconds into the first round, the fight was mercifully stopped, and Louis was declared the winner by technical knockout.

Louis went on to the longest single reign as champion of any heavyweight boxer in history. When World War II came, he enlisted in the still segregated U.S. Army. A friend objected. “It’s a white man’s Army, Joe” he said, “it ain’t a black man’s Army.” Louis replied: “Lots of things wrong with America, but Hitler ain’t going to fix them.”

After Louis’s death in 1981, President Ronald Reagan waived eligibility rules to enable Louis to be buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery. Joe’s famous former opponent and life-long friend, Max Schmeling, helped pay for his funeral and served as a pallbearer.

Following Louis’s historic victory over Schmeling, Jimmy Walker, the flamboyant New York Irish politician and avid boxing fan met Louis at a gathering of sports writers. Walker was always a quick man with a quip. He shook Louis’s hand, and said, “Joe, you have laid a rose on Abraham Lincoln’s grave.”

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Keep America Great Alive

Conservatives need to practice what they preach in body as well as mind.