Tending to our humanity in a technological age.

The Western in the Time of Coronavirus

As an expert on American pop culture, I am used to being called upon in a crisis. For some reason, when Americans are faced with a catastrophe, they start worrying about how it might affect their favorite movies and television shows. With an essay called “The X-Files and 9/11” to my credit, I seem to be the person to consult about the cultural impact of the current coronavirus pandemic. Although I have my doubts about the long-term effects of any crisis on movies and television, I thought I’d speculate on how the coronavirus might change our perception of perhaps the most fundamental genre of American pop culture, the Western. In particular, I tried a little thought experiment and asked myself: How would some of our classic Westerns hold up in the time of coronavirus? Would some of them perhaps need to be revised or rethought under the current circumstances?

Take, for example, one of the most famous of Westerns, John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939). Ford came up with the brilliant idea of turning a group of random travelers into a microcosm of American society by cramming them all into a stagecoach. But there’s the problem right away: Ford’s characters do not observe proper social distancing and thus Stagecoach just would not do in our current climate of opinion. Moreover, the film begins with a prostitute being run out-of-town in an effort to clean up the community. Today, the local authorities would classify her business as “essential,” along with liquor stores, marijuana dispensaries, and state lotteries, thus allowing her to stay in town and practice her profession. At least the film anticipates current policies in one respect: the prostitute is joined on the stagecoach by a gambler and a whiskey salesman. As for the John Wayne character, the Ringo Kid, he is being hunted as an escaped convict; today he would have already been released from jail to protect him from the coronavirus. Finally, among the irreparably dated aspects of Stagecoach, it includes a villainous banker absconding with his depositors’ funds to save himself financially. Today of course he could have remained in his office to be bailed out by the federal government, provided his bank was “too big to fail.” Alas, Stagecoach really does not speak to our era.

Or take Gary Cooper in the classic Western, High Noon (1952). Marshal Will Kane has a rendezvous with destiny, now that a criminal he put in prison has been released and is coming to town with his gang to kill Kane. In High Noon, Kane is terribly disappointed that the streets of Hadleyburg are deserted as he walks toward his fateful encounter; the cowardly townspeople have not rallied to his defense. But today the streets would be deserted because of the governor’s “shelter in place” order, and the townspeople would be regarded as heroes for staying at home and self-quarantining. At the end of the movie, Kane turns in his badge in disgust at the whole community’s failure to support him. Today, he would probably resign because he couldn’t bring himself to arrest an old lady for not wearing a face mask outdoors. Back in his day, Kane probably associated wearing face masks with criminal activity. How times have changed!

When I was in my teens, my favorite Western movie was the Burt Lancaster/Kirk Douglas Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), a “shoot ‘em up” Western if there ever were one. But today the most dramatic event in the film would probably be Doc Holiday being forced to close down his dental practice because of all his coughing. As for the infamous Clanton gang, as cattle rustlers they would also be out of work. With the nearest meat packing plant shut down, there would be no money in the cattle business anymore. With much of Tombstone unemployed and confined at home, the Earp Brothers, if they even bothered to show up at the O.K. Corral, would have brought their wives along and a buckboard, and simply borrowed some horses for a ride in the country. Hayride at the O.K. Corral, anyone? I don’t think so.

To return to the old master, John Ford, how would The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) fare today? First of all, its premise is that a sitting U.S. Senator (Ranse Stoddard) quietly returns to his state just to reconnect with his constituents. Audiences today might find that premise a bit hard to swallow. And the rest of the story would seem implausible too. Beaten up by a thug, Stoddard has to put his life back in order. He takes a job bussing tables in a restaurant, but although he does prominently wear an apron, he doesn’t wear a face mask and that would be the end of that job for him. He moves on to try his hand as a schoolteacher; no luck again—his class would have long since been shut down and he probably didn’t have access to Zoom. What is worse is that he was teaching his students about the U.S. Constitution. A lot of government officials today do not like having the American people reminded about the Constitution and their rights under it. Liberty Valance just wouldn’t fit today’s mood. After all, its famous tagline—“print the legend”—flies in the face of today’s mania for fact-checking.

Yet another Ford film, Wagon Master (1950), inspired a successful TV series called Wagon Train (1957-65). It would at first seem promising for a contemporary adaptation. An intrepid group of latter-day pioneers could circle their RVs instead of their wagons and head west under the steady leadership of a Ward Bond-like wagon master. They would be fleeing the impoverished economy and petty tyrannies of an East Coast governor as in New York. Overcoming all sorts of hardships along the way, our heroes and heroines would cross the nation and eventually end up in California. There they would find an impoverished economy and the petty tyrannies of a West Coast governor. Perhaps a modernized Wagon Train might not be so uplifting after all.

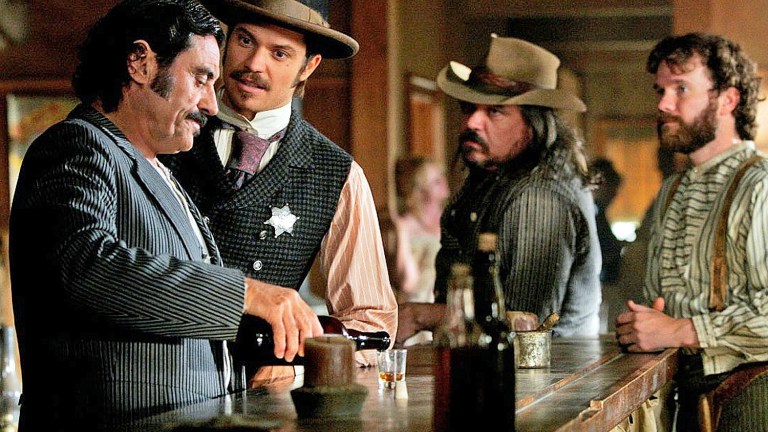

Of all the great Westerns I can think of, perhaps only the television show Deadwood (2004-2006) could still pass muster today. With the story taking place in illegally occupied Sioux lands, no government is in force, neither state nor federal. As a result, a governor would not get to lock down Deadwood. Al Swearengen’s Gem Saloon would stay open and prosper. Sol Star and Seth Bullock would never have to close down their hardware store, even if they brazenly had paint and carpet products on display. What’s more, the chief industry in Deadwood is gold mining, and the precious metal would come in handy when the dollar is losing value because of efforts to maintain “liquidity” via inflationary monetary policies. Today Deadwood might even have a happy ending. And the first season featured a storyline involving a smallpox plague and the desperate search for a vaccine. Let’s bring Deadwood back. Clearly it’s the Western for our moment.

As for my favorite Western on television when I was a kid, Have Gun—Will Travel (1957-63), forget about it. The “Have Gun” part would run afoul of many states’s efforts to exploit a health crisis to implement gun control. And don’t even get me started on the “Will Travel” part. Today the title would have to be Have Virus—Can’t Travel.

It’s painful to say it, but after going over these cases, I’m beginning to worry that the classic American Westerns would mostly seem out of place in the world today. Westerns like Stagecoach and High Noon seem to speak of a different world, a world in which men—and women too—were heroic. Faced with a challenge, they went out and faced it. The classic Westerner is a risk-taker, acting out of courage, not fear. The Western celebrated traditional American virtues—independence and self-reliance. It portrayed people who could be relied on to work together and take care of themselves.

But hold on—if that is true, maybe the Western does speak to us today after all. We have repeatedly witnessed heroic responses to the global pandemic, especially from all the health care workers who have willingly put their own lives at risk to save others. And think of all the ordinary Americans who have worked doggedly, at personal risk, to keep our supply chains functioning and our stores well-stocked (despite occasional glitches). Our elites keep regarding common people as helpless and utterly dependent on government to save them, often from themselves. And yet it has been truckdrivers, mechanics, grocery operators, farmers, and all sorts of blue-collar workers who have shown up at their daily jobs and kept the country running. Companies like Walmart and Amazon have kept Americans provisioned in ways that no government agencies ever could. We are fortunate that our legion of bureaucrats never had the leisure time to think about our situation and conclude that market institutions are incapable of delivering food to millions of people reliably and fairly. Only the fact that they could see our supermarkets running almost normally forestalled our authorities from calling for the entire food industry to be nationalized and centrally planned. Our government officials, most of whom have never worked in a functioning business in their lives, have no idea how an economy works. It’s something economists call “spontaneous order,” and it beats central planning all the time. Allow people to pursue their self-interest (and be rewarded for successfully doing so) and they will generally solve their problems by pooling their resources and cooperating with each other, just as used to happen in the Old West.

So the traditional Western can teach us something—even today. It can remind us of the individual heroism that has carried America through crises throughout its history. And it can recall the American capacity for association that the great nineteenth-century observer of our country, Alexis de Tocqueville, noted in its first few decades. When faced with a problem, Americans typically come together to solve it on their own initiative and at the local level, without interference from a distant (and often clueless) central government. It’s a classic scene in a Western—a whole town spontaneously coming together to erect a schoolhouse or rebuild a barn that just burned down—the perfect Tocquevillean vision of a free people. Above all, the Western is the most American of genres because it holds up freedom as the highest value, and it regularly returned to the theme of human beings who are willing to make sacrifices to preserve their freedom. That’s what the Western frontier has always meant in the American imagination—the perpetual willingness of Americans to pull up stakes and move on whenever their community starts to constrict their liberty too much. The Western doesn’t portray an easy world, and indeed the price we pay for freedom is one of the central ideas of the genre. Given the way that civil liberties are being suspended all over the United States these days, perhaps we could use a revival of the Western in America. John Wayne, where are you when we need you?

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Lincoln speaks against the mob.