The 1776 Report demonstrates a more sophisticated grasp of history than that of its critics.

Restore Authority to Education

Our K–12 students need guidance out of ignorance.

In my first article on education in The American Mind, I argued that conservatives ought to focus more on the reform of K–12 education than attempt to undo the corruption of higher education. I indicated that this reform must happen in every family and community, and that we cannot look to public policy to save us.

Here, as promised, I outline the terms of reform. I argue that, in the most general terms, what American education needs is authority and authoritativeness. It needs discipline. It needs dogma.

Whoa there, cowboy. Aren’t our schools already too authoritative, too dogmatic? Don’t they exercise a prisonlike hold on their captive students? Shouldn’t the goal of education be freedom instead of meek submission? And again, aren’t our current problems with education rooted in the prioritization of political correctness over the knowledge, the “content,” and the skills which are the real meat of learning, the real purpose of our schools?

Since my first article, Spotted Toad published in this same space a persuasive account of recent tendencies in K–12 education. He argues, in effect, that a new authority and authoritativeness is in fact already eclipsing the old supposedly morally neutral, non-authoritative meritocracy. Indeed, schools cannot escape their role as purveyors of authority. In Spotted Toad’s description, the “successor ideology,” the religious revival of the Great Awokening, is a return of the idea of authority in the American classroom and lecture hall, but the authority it respects is a terrifying, barbaric, illiterate one.

What’s more, it is also a return (to borrow an idea from Eric Voegelin) of the gnostic heresy in politics and education: truth is a mystery, always changing, that dwells in the future, and only the Party knows what it is. All who stand against this truth, which Leo Paul De Alvarez calls “a private vision, a dream, as irrational as the predictions of the astrologer or palm reader,” are evil.

In the face of this ascendant dogma, it will not do, as conservatives have done for many decades, to fight for school choice, for charter programs and alternative curricula and voucher programs, to develop alternative and private Christian schools and homeschooling cooperatives. These things are all well and good; indeed, school choice is something like a civil right, and school boards and teacher’s unions, when they oppose charter schools and voucher programs, often speak of the affected students as serfs and vassals who are rightly tied to their administrative fiefdoms. Parents, teachers, and leaders involved in these schools often make heroic sacrifices to oppose these forces, and they are doing the necessary work of building healthy local institutions.

But this work is not nearly enough, and many of these alternative schools suffer from the same problems as the public schools. It is not enough to insist upon high academic standards or rigorous content. There is no shortage of private and charter schools which emphasize high performance on standardized tests and high rates of college admission while giving apparently no quarter to social justice ideology.

The Rule of the Ignorant

Conservatives applaud these institutions and strive to make their no-nonsense, results-based approach the model for higher education as well. But, as Spotted Toad also makes clear, this does nothing to combat the dangerous dogmas of the Great Awokening. Rather, it can only serve to fan the flames as those who succeed through academic means but without any healthy and robust sense of history and human purpose come to recognize “that their role in the new racial and sexual dispensation is contingent and tenuous,” and seek to “‘get right’ with this new world through rituals of rhetorical and political self-sacrifice.”

Of course, the graduates of, say, a test prep charter in Arizona or a “success academy” in inner-city Boston aren’t members of the elite, desperately seeking quasi-religious validation of the legitimacy of their high perches in the ruling class. They’re mostly looking to be able to provide comfortable lives for themselves and their families. They do not seek to join the fervent, gnostic death-cults which organize demonstrations at their universities.

But they’re also unable to provide much of an argument against them. The same is true of many Americans. In response to the shrieks and calls to action from social justice warriors, environmentalists, and transgender activists—all the pressure groups smearing together in this brave new intersectional world—they are like the poor Christian who admits, with not much embarrassment, that, yeah, he should go to church more, or that he’s just not very religious.

What schools need is authority, and they need it on every level. That many schools and teachers are ill-equipped to exercise authority, and that their sources of authority, such as they are, are dubious, doesn’t change this. The solution to the problem of authority poorly exercised is not to abdicate but to overthrow and replace.

By “authority” I do not mean the power exercised by the strong over the weak. In crushing bureaucratic ways, our institutions, including our schools, exercise this kind of force all the time. In soft and subtle ways Americans, because they are tyrannized, learn to be tyrants. They learn to use laws and procedures as cloaks for the imposition of their wills, just as others in their lives have fallen back on the dumb and convenient authority of policy as an excuse not to have to refer to the standards of reason and morality.

I refer, rather, to authority in the sense that the one who exercises authority in turn stands in obedience, in recognition of a received commission, not as blind devotee of democratic or bureaucratic will but as a grateful recipient of a tradition. I speak of authority as a kind of piety, or as consequence of piety, in the etymological sense: the pious one is faithful to the charge that has been given to him. We lack authority because we are unfaithful.

Our schools, at the undergraduate level but also at the K-12 level, lack authority in the first place because they have abandoned the canon, have perverted the liberal arts, neglected classical languages, and most importantly, have traded required curricula for the elective system.

As Eva Brann notes, elective education is founded on an absurdity: “Real choice depends on knowledgeable judgement, and such judgment comes after education, not before it.” By enacting elective education, schools abdicate their authority and pass on themselves a great judgment, “the judgment that students are as well oriented in the orbis intellectualis, the intellectual universe, before they choose their course of study as [the faculty] will ever be.”

Chaos or Law?

This turn away from the tradition, this abdication of authority, has analogs and consequences in politics and morals. The same posture which has led schools and teachers to declare, “It doesn’t matter what students are reading, as long as they’re reading!” is at work in the encouragement of students to “get involved” in causes and “speak out” about issues about which they are profoundly ignorant.

Of course, our schools are not really neutral about the causes their students champion. In fact, one is far more likely to find such neutrality—along with far less activism generally—in schools which recognize the authority of tradition, because the presence of the great minds and works of the past tends to inspire humility and awe, not indignation and a crusader spirit.

Insofar as there is a canon, and authority in our schools, it is in service of a squishy sense of tolerance. Powerful books like Elie Wiesel’s Night and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird are reduced to encomia of liberal pieties: in the dark past, mean people judged other people for being different, but we don’t do that anymore.

But the loss of authority in our schools can be seen on a much more elemental level as well. One need not be a tweedy classicist yearning for the bygone days when secondary school students all studied Latin to recognize this missing component in education. You don’t have to look at the books and lessons. You can see it on the faces of the teachers, in the cowed words of the administrators. They’re scared of their students.

I don’t mean that they think their students will hurt them physically. Rather, they are afraid to assert any real authority, to stand in the places of adults and representatives of a good and lasting order and pass any serious judgment on the habits and choices of their students.

But this fear has real consequences in classroom discipline, too. As one of my graduate students, a high school teacher at a public charter school, put it, “If my students realized the full extent of my legal powerlessness in the classroom, and if they were so inclined, they could ensure that we never learned anything for the rest of the year.”

But many students do realize that their teachers’ power over them is an illusion. They are amiable, and they play whatever games are required to earn their grades and get ahead, but they never learn to respect their teachers or their educational inheritance simply because those teachers never assert the authority of that tradition. At most, our teachers demand the respect of a shopkeeper, who insists that if he is to give you his goods, you ought to pay him for it: a certain modicum of order is necessary, if only so that we can get through this material together, and you can do well on the test.

It is no wonder that our students, then, go on to demand in college exactly what they have been trained to expect from their earlier education. For their money and time, students demand the grade and the degree, a trade and its skills, and, finally, validation of their own feelings and sensibilities.

To solve the crisis of higher education, we must confront the rot in our primary and secondary schools. To do that, our communities must bring back authority to our schools at a time when that authority has all but disappeared. Where can that authority come from? Only from our fundamental—and natural—laws.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

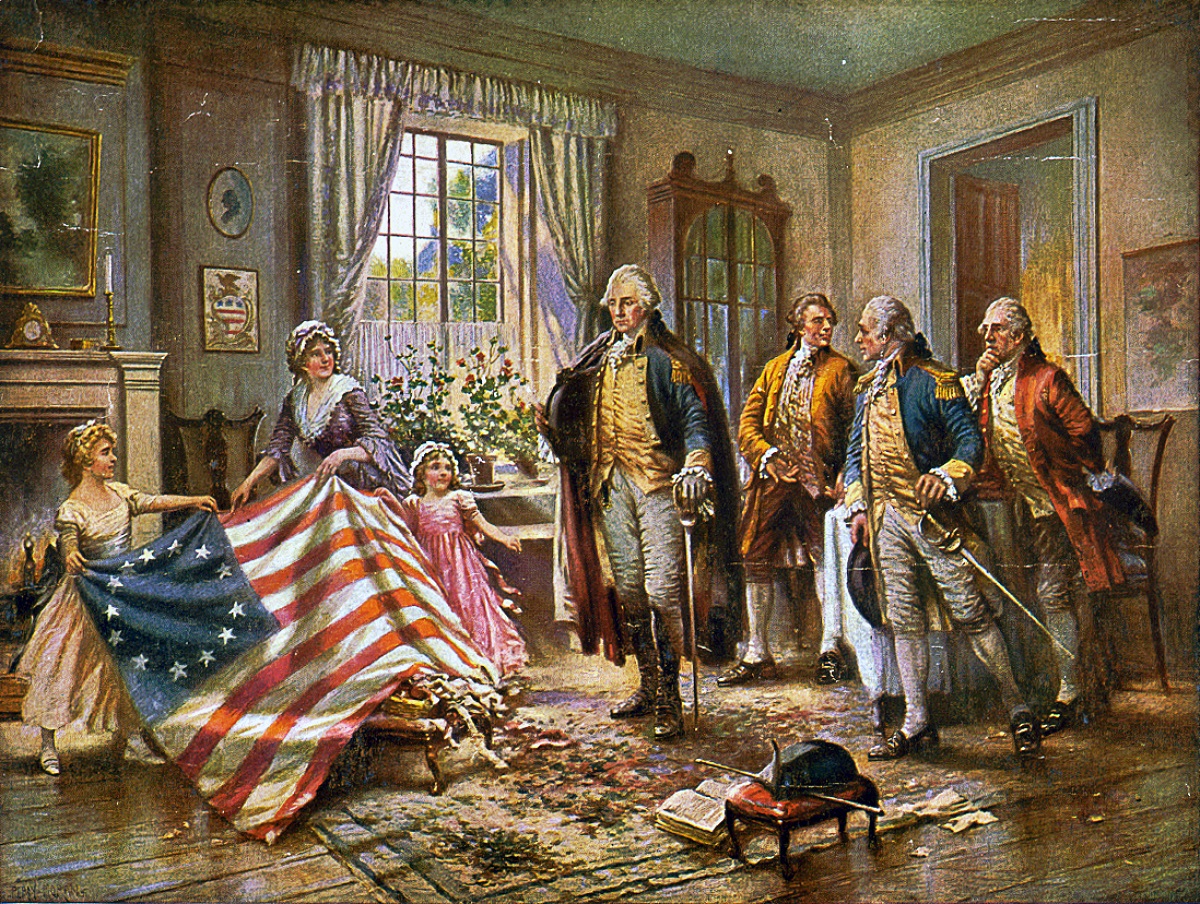

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Don’t let the commies win.

This is the Right’s greatest opportunity in decades. Will we take it?

Shape your soul and the country will follow.

Big Biz, Big Tech, & Higher Ed are not your friends.

Our proud nation and history deserve better.