The decisive move will show the CPC we mean business.

When China Sneezes…

How U.S. Supply Chains Caught A Cold.

It is one of the top economic, technological, educational, and cultural centers for all of China. And by the end of January, it had ground completely to a halt.

Nearly half of all Fortune 500 companies have offices or factories located there. Key exports include machinery, electrical equipment, electronics, retail goods, and automotive parts. A massive metroplex of more than 11 million people clustered along the Yangtze River, Wuhan has grown rapidly in the past three decades as an inland industrial hub and river port. Between 2007 and 2018, its gross domestic product (GDP) increased nearly 500%, topping out at more than $210 billion in 2018.

But in mid-January 2020, reports began trickling out about an outbreak of a new type of respiratory illness (now called COVID-19) in the city.

The Chinese government, remembering the lessons of previous deadly outbreaks such as SARS and the H1N1 swine flu, took immediate drastic measures to contain the virus to Wuhan, shutting down transportation to and from the city and instituting strict curfews on January 23. Given the rapidity with which COVID-19 spread and its worrisome early mortality rate, China was anxious to keep the contagion from spreading to its other cities—and the world.

Now, 45 days on from the initial outbreak, the world remains gripped with uncertainty about the threat of COVID-19. The virus has spread to more than 60 countries, with 20 of those battling 100 or more cases.

Per the World Health Organization, as of March 13, the number of cases reported globally stands at a little more than 145,000, with a mortality rate of 3.7%. China remains hardest-hit, with more than 80,000 cases, though the rate of infection has tumbled in recent days as the drastic containment measures have taken effect.

Through it all, however, has come a different sort of “black swan” concept: what happens when the manufacturing engine of the world suddenly switches off?

The Center of Everything

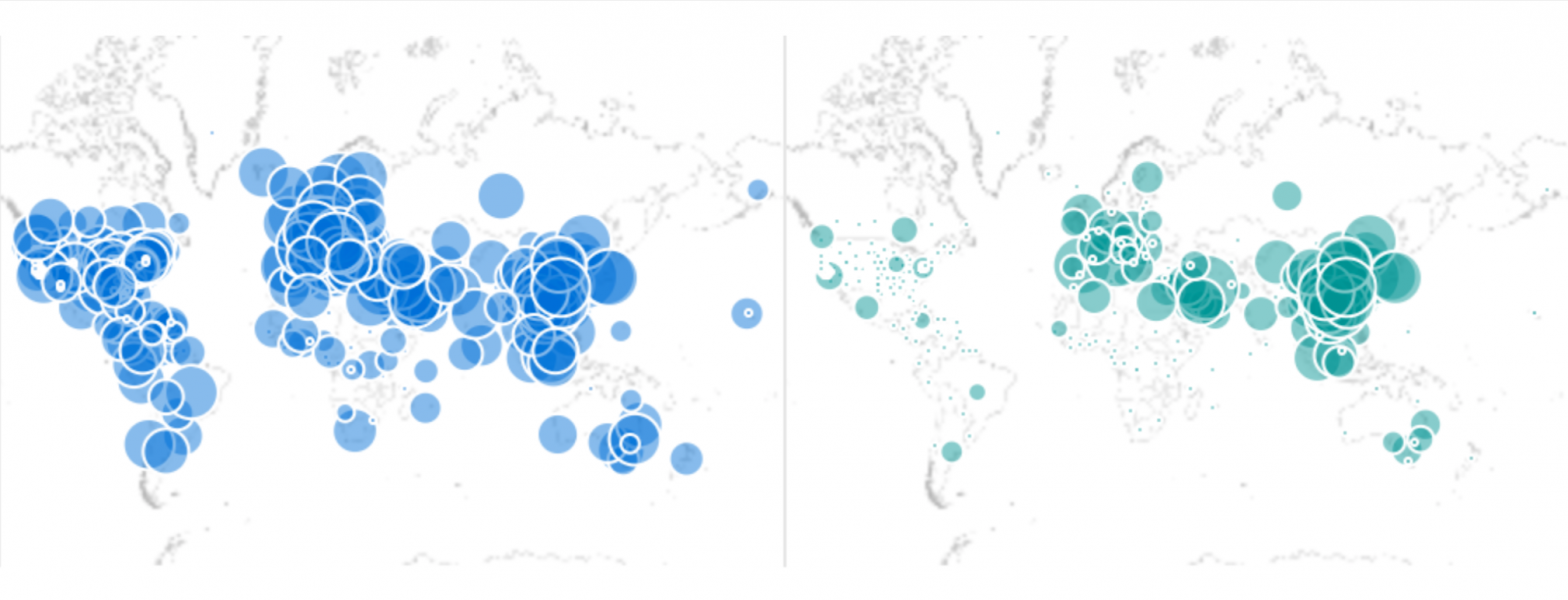

According to estimates from the United Nations, China represents 28% of the world’s manufacturing output, with a GDP of more than $13 trillion. The United States is next closest in manufacturing output at 17%, having been surpassed by China in 2010. However, what is even more important is how China achieved such tremendous dominance.

Free-marketeers will often use the analogy that capitalism doesn’t just provide for a dynamic division of the “economic pie,” but also increases the size of the pie by creating new opportunities for wealth. To an extent this is true, particularly in industries that are less reliant on capital assets and infrastructure. Through the magic of for-profit lending, banks can increase their bottom line without increasing headcount or investments into new buildings. A new technology firm can create a piece of software that takes the world by storm and does billions in revenue.

But this dynamic takes on a different character when it is applied to the manufacture of real goods. Supply chains are often zero-sum propositions, particularly where finite transport capacity or scarce raw materials are involved. There is an upper-bounded limit enforced by harsh reality. Ships, aircraft, railroads, and trucks can only carry materials and goods so fast from point to point. There is only so much of many metals and minerals available. Geopolitical factors can overnight tip the balance of supply and demand.

China has aggressively subsidized the expansion of its manufacturing base and transport infrastructure to overcome the natural chokepoints that occur during rapid growth. For example, shipping cargo on China’s Trans-Asian Railway is an expensive proposition compared to ocean transportation but takes about half the time. To encourage participation, China was estimated to be subsidizing up to half of the per-ton cost for shippers.

Similar subsidies for port operations and parcel shipments from China to Europe and the U.S., and reduced export taxes on certain products, have realigned the global logistics industry around Chinese-origin cargo. Seven of the world’s ten busiest ports are Chinese, with enormous throughput of imports, exports, and trans-shipped cargo (switching cargo at port from large blue-water “mother” vessels to smaller “feeder” vessels for further shipment).

This is all in keeping with China’s three-domain strategy for manufacturing dominance: logistics, production, and raw material ownership. By allowing China to co-opt or control each domain, the rest of the world benefited from lower prices of goods, while mostly pretending that Chinese human and environmental abuses were not part of the bargain.

But as we have seen with COVID-19, the benefit of interdependence becomes a lethal contagion to the world’s economy and the logistics infrastructure upon which we all depend.

Three Weeks Behind

Perhaps the two least-understood factors in early analysis of COVID-19’s impact to U.S. retail and manufacturing supply chains are those of transit times and manufacturing cycles in China.

Numerous media reports were pushed out in February warning of severe declines in U.S. import from January to February, with the implication that the shutdown of China in January was to blame. Rarely noted, however, is that this is normal. Ocean cargo vessels sailing from China are typically full just before year-end, as American companies rush to get cargo on-water and count the goods towards the current year’s sales.

As I was told by the CEO of an international logistics provider with locations in China, Hong Kong, and the United States, this is an annual event. “We usually see a big rush of activity before the New Year celebrations in the U.S. and China. During Chinese New Year, we expect ocean carriers to skip a week or two of sailings since no cargo is moving, then reopen for business. It has been a known factor every year I’ve been in the business.”

Because of the distance between China and the U.S., ocean vessel transit times are anywhere from fifteen to twenty days to U.S. West Coast ports like Los Angeles, Long Beach, Oakland, and Seattle-Tacoma. To East Coast U.S. ports like Savannah, Charleston, Norfolk, and New York, it’s more than a month. This makes U.S. port volumes a lagging indicator of Chinese activity by three weeks or more. Claiming a specific effect based on February data is simply inappropriate for measuring the impact of COVID-19.

Then there is the timing of U.S.-China supply chains. Purchase orders are sent to Chinese suppliers weeks or months ahead of the expected manufacturing and shipping dates. Depending on the product, it could be as little as two weeks prior to shipment, or as much as six months.

Importantly, these purchase orders don’t stop during an anticipated shutdown period—the timing is simply accounted for in the U.S. company’s demand forecast. But with an extended shutdown, the Chinese companies fall behind production schedules. To compensate for this, the suppliers in China will change their terms of payment and essentially force many buyers to compete for the “first” space by prepaying for their goods. We have now entered this period of capacity competition.

A Tale of Two Recoveries

Due to the peculiar nature of COVID-19, especially its longer-than-typical delay from transmission to onset of symptoms in many people, the virus will have a “fat tail” in terms of its impact on global supply chains. The ways in which countries respond to the introduction of the virus seem to shape the type of supply chain recovery.

China, South Korea, and Japan all responded quickly and aggressively to the COVID-19 outbreak. Forced quarantines, mandatory testing, and close observation by medical authorities have rapidly limited the impact of the virus. Factories are quickly coming back online—some 80% are working again by most estimates—as workers are cleared to return and logistics providers are reopening for business.

The ocean carriers will increase rates as all the backordered products begin to leave the manufacturers. This will be exacerbated by the ocean carriers not adding extra capacity to the market, preferring instead to keep available vessel space tight. The overseas buyers want their delayed goods, and they’re paying up-front and higher prices to do it. This rapid return to business as usual is called a “V-shaped recovery”, where activity resumes almost as quickly as it shut down.

However, nations like the United States will see something closer to a “U-shaped recovery.” That is, it will not only take longer for U.S. companies to restock shelves and empty inventories, but it will also take longer to clear the backlog of purchase orders that continued to accumulate during China’s prolonged shutdown. The competition for ocean vessel space will likely remain fierce, keeping vessels full and rates higher. This will take months to normalize as the supply chain pipeline slowly refills.

Enormous companies like Amazon and Wal-Mart that have vertically integrated their factory-to-store operations will see less of an impact. The hardest hit will be the companies who suddenly find themselves having to outlay a lot of cash—or wait weeks and months for their product—to resume business.

Here is the weakness of just-in-time supply chains revealed, arguing for companies dependent on Far East-origin supply chains to explore reshoring or new inventory management processes.

Now three months on, COVID-19 has yet to make its full impact felt. The variability and timing of its spread, and uncertainty over treatment modalities, may well produce one or more “false bottoms” in supply chains and markets.

An unexpected event such as a port shutdown in the U.S. could well be looming in the background. But given that China was the first- and hardest-hit, and has seemed to emerge from the chaos of the January outbreak with new tools and lessons learned, it would seem that the worst is behind the world’s supply chains for the moment. Lingering fears and bouts of panic will continue to occur throughout 2020—but at least it isn’t the end of the world as we know it. And that’s not nothing.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

In wars, men die.

For the first time in centuries, we’re bringing it all back home.

Facing up to the failed state of America's mandarin class

Don’t let the Left use your panic for their gain.

We blew it. Normies are paying a heavy price.