The decisive move will show the CPC we mean business.

The Return of Fortuna

Coronavirus calls for Machiavellian virtue, not technocracy.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the historical moment we find ourselves in. Pundits, scholars, and public figures—being prone to hyperbole—often overstate the gravity and moment of events. But this time it is almost certainly different. When this is over, the world will have changed.

The coronavirus pandemic has become, and will likely remain for the foreseeable future, a brutal and devastating reminder that innumerable aspects of our lives are subject to forces beyond our control. More importantly, it is a rude awakening for those of us who think the world can ever be any other way.

There is a contemporary tendency to try and sever politics from fundamental and first-order questions about the nature of reality. Politics, and our political institutions, are understood in narrowly procedural terms, legitimized by aggrandizing claims of expertise that reduce what are ultimately political questions to dry technical problems to be solved by experts.

While this understanding reduces politics to matters of technocratic expertise, it presupposes an unexamined view that both the social and natural world can be systematized and subdued, brought under the control of rational creatures like human beings. But, as we are rediscovering now, these underlying assumptions are flawed. They don’t reflect the world we actually inhabit.

The Limits of Control

To better understand both the situation we find ourselves in, and how we must respond as we reemerge out of this crisis, we should turn to a perhaps unorthodox source, Niccolò Machiavelli. While his name is now commonly, and unjustly, associated with an unseemly and sinister account of politics, Machiavelli’s politics is built on a rich and original account of fortuna and its role in human affairs that we would do well to consider in the present moment.

While they disagree about what, exactly, Machiavelli means by it, scholars and astute readers virtually all agree that fortuna is at the heart of Machiavelli’s understanding of the world. It plays a central role in shaping and deciding the outcomes of human affairs.

The penultimate chapter of The Prince (XXIV) contains Machiavelli’s clearest and most explicit account:

It is not unknown to me that many have held and hold the opinion that worldly things are so governed by fortune and by God, that men cannot correct them with their prudence…that one need not sweat much over things and let oneself be governed by chance [fortuna].

Machiavelli says he has at various points “been…inclined to [this] opinion,” but that he ultimately rejects it. Instead, he says, “fortuna is arbiter of half our actions, but also…she leaves the other half, or close to it, for us to govern.”

Machiavelli’s teaching was at least partially driven by what he identified as the problem with this initial view, in which human affairs are governed partly by fortune and partly by God, with no room for human intervention. This, he thought, entailed a kind of fatalistic passivity that allowed fortuna to ride roughshod over us. Machiavelli rejects this view and, “so that our free will not be eliminated,” proposes that mankind may control at least half of the world’s affairs.

This he may do by exerting virtù, virtue or manful fortitude, which for Machiavelli always entails the capacity to overcome and minimize fortuna. But no such capacity is absolute. While fortuna can be managed and regulated, it cannot ever be entirely subdued. Not even Cesare Borgia, one of Machiavelli’s heroes, was able to overpower the full force of fortuna.

This account makes flexibility and adaptability into virtues. Contingency and flux characterize the world. Survival and stability require not just strong foundations, but often require refoundings and continual adaptation to the changing conditions of the world. Much of the Discourses is devoted to not only the founding of states, but the refounding of states to meet the ever-changing challenge posed by fortuna.

Technocracy and its Discontents

Machiavelli’s ire was aimed squarely at what he saw as the passivity of his day, rooted in an “ambitious idleness” that encouraged a kind of providential fatalism. But if ambitious idleness characterized by passivity captures the predicament of Machiavelli’s age, it doesn’t capture our contemporary predicament, which is better described as an unambitious idleness driven not by passivity, but by hubris.

This idleness is not driven by a longing for “imaginary republics” or a focus on the transcendent, but instead by an overconfident hubris that we have essentially “figured it all out” and arrived at an end of history moment with little left to do. In addition to producing the kind of cultural and social nihilism that Ross Douthat captures in The Decadent Society, this hubris has helped produce sclerotic and decaying political institutions unresponsive to democratic and geopolitical pressures.

These political institutions are undergirded not just by democratic legitimacy but by technocratic legitimacy. Technocracy, in its very essence, implies that technology and knowledge can render fortuna obsolete. In After Virtue (1981), Alasdair MacIntyre suggests that modern managerial expertise is predicated on the predictive social sciences. These offer a systematic understanding of reality that gives the managerial class access to a superior form of knowledge and enables them to effectively govern society.

This requires the underlying premise that the natural and social world are systematic in a way that makes them predictable, thus enabling predictive knowledge and effectively banishing fortuna from the world. This, MacIntyre warns, leads to overly confident claims that don’t reflect the world we actually live in.

There is no point listing here the numerous examples of technocratic overreach producing claims and predictions that turned out to be false or overly confident. Our present moment is itself example enough. The coronavirus pandemic is an exogenous shock that our reigning authorities either failed entirely to predict or neglected to prepare adequately for. It is a reminder that we are still highly vulnerable to natural forces beyond our control.

The Virus and Virtù

This reminder should serve as a wake-up call to the hubristic autopilot that has characterized liberal technocratic governance since the end of the Cold War. Exogenous shocks, like pandemics, can never be entirely eliminated. Hubris has translated into political and economic decisions at the highest levels that have made us more vulnerable.

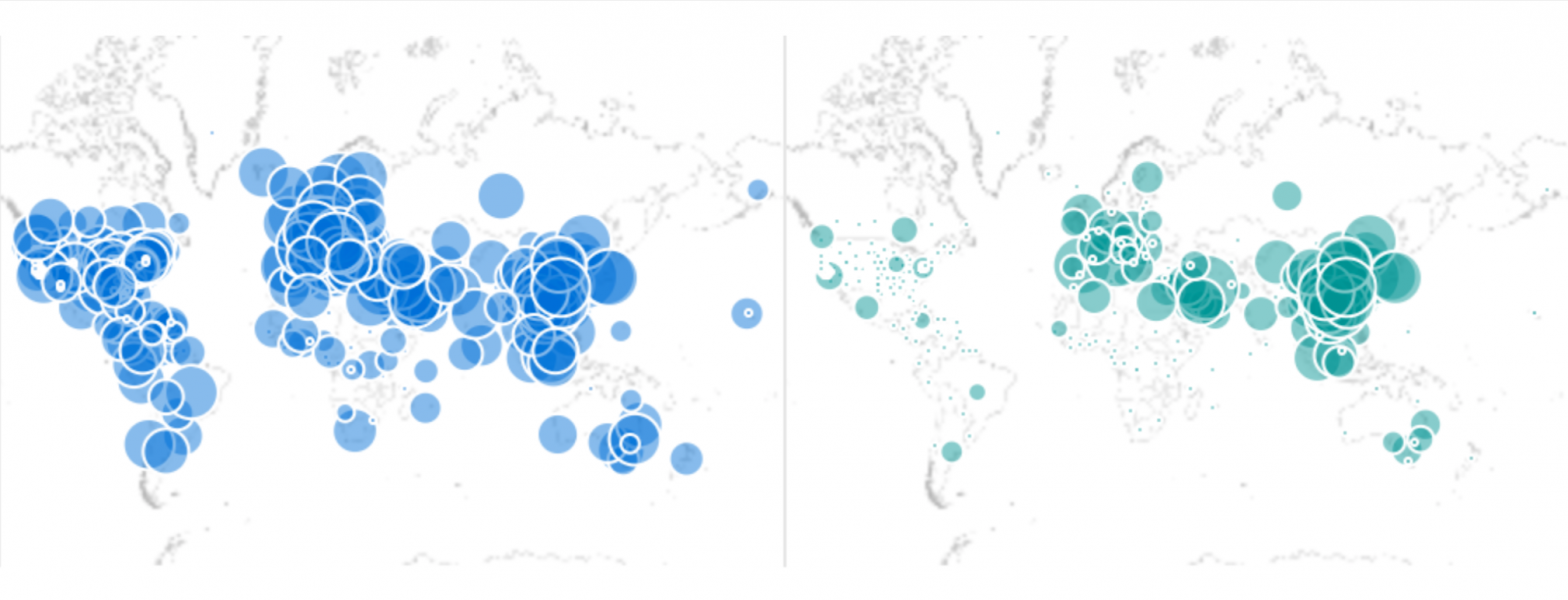

This crisis also represents a watershed moment in the relationship between the West and China. For too long, political leaders on both sides of the aisle have pursued policies and geopolitical decisions that have enabled the offshoring of supply chains that have both economic and strategic significance.

American outsourcing of the production of key items like masks to China is now proving to be a major challenge in the American response to the pandemic, given that China is unwilling to use its production capacity to help produce masks for Americans. That economic power is essentially political power is something the Chinese government fully understands, but it is something we in the West appear to have forgotten, and need to rediscover.

By promoting and championing polices that led to the offshoring of strategically vital supply chains and global manufacturing to an untrustworthy regime, we both made ourselves more vulnerable to an exogenous shock like this pandemic, and more broadly enabled the rise of a hostile power with which we find ourselves on a collision course.

The Chinese regime has exploited our openness to infiltrate universities and institutions, whether that be through the Confucius Institutes set up on campuses to stifle criticism of China, or through elite capture at universities through programs like the “Thousands Talents Program” which is (allegedly) used to steal intellectual property, research, and technology. China has exploited our attempts to integrate it into the global order with some success, managing to co-opt and capture international institutions like the World Health Organization.

We find ourselves in this situation not because of circumstances that are beyond our control, but because of circumstances that we enabled via political and strategic decisions over the past half-century. In perfect Machiavellian dualism, this failure of virtù has left us more open to chance and fortuna than we need to be.

It didn’t have to be this way, and it doesn’t have to stay this way going forward.

Virtuous statecraft is more vital than ever now, which means strategically reconsolidating industrial and economic capacity so as to minimize our vulnerability to exogenous shocks like pandemics and serious political threats like the Chinese regime. This means building the dams and canals that minimize and manage our risk and vulnerability to things that we can never fully control, like natural disasters or pandemics.

This isn’t going to be easy, and is going to require virtù. Coronavirus has reintroduced a degree of radical uncertainty and flux into our lives that many of us have never experienced and that we have collectively forgotten exists. But uncertainty, and fortuna, are inescapable features of our world. We must now relearn this truth, and respond accordingly.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

In wars, men die.

For the first time in centuries, we’re bringing it all back home.

Facing up to the failed state of America's mandarin class

Don’t let the Left use your panic for their gain.

We blew it. Normies are paying a heavy price.