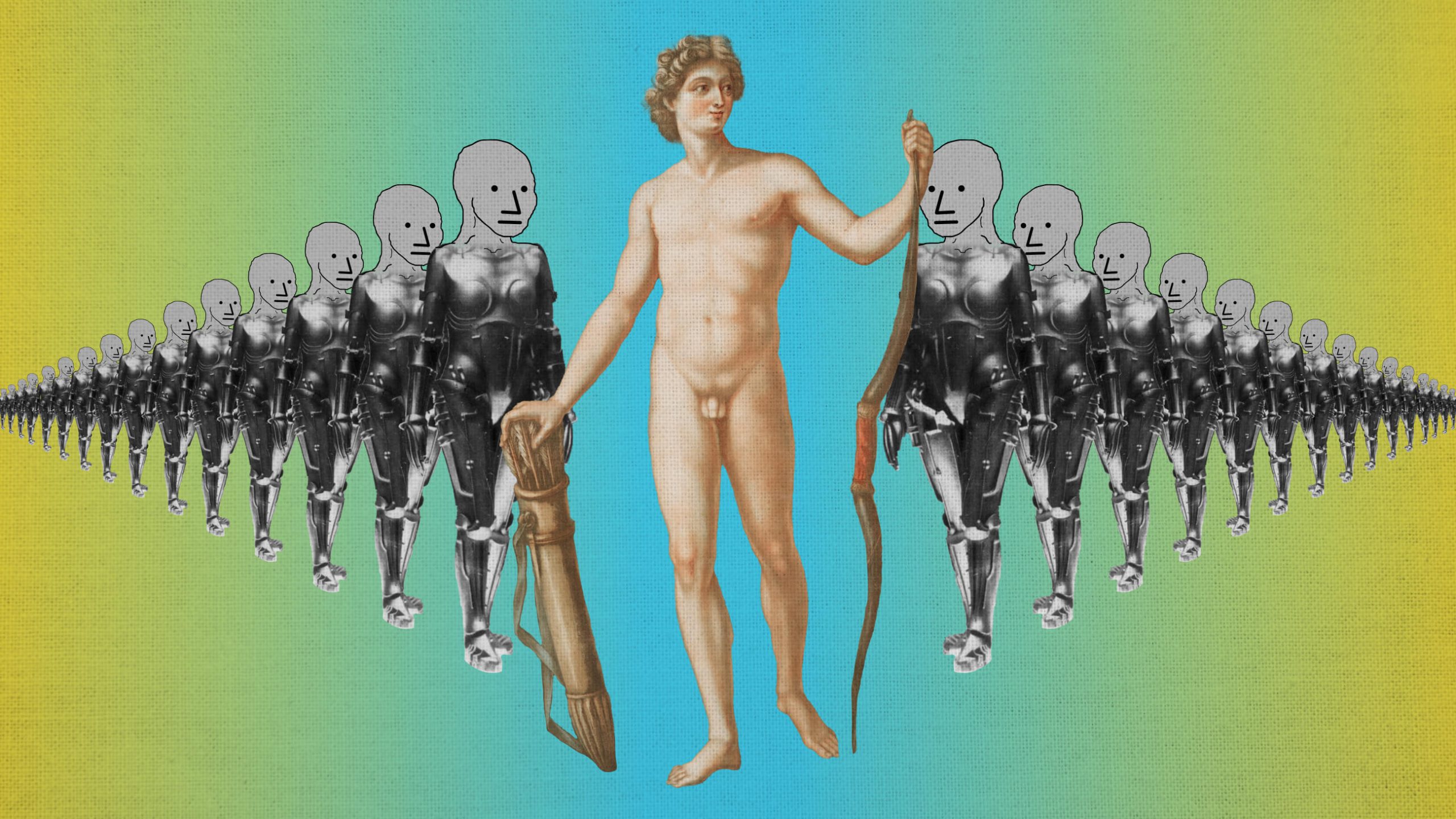

The digital era has awoken an ancient revulsion with the flesh.

Physical Education, Spiritual Fortitude

To stay free, you must learn to be courageous.

In his 1978 Harvard Address, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn observed a dramatic “decline in courage” in the West. “The Western world has lost its civil courage,” a loss “particularly noticeable among the ruling groups and intellectual elite, causing an impression of loss of courage by the entire society.”

This decline, especially among the political class charged with leading and securing the interests of ordinary Americans, was on full display throughout the annus horribilis of 2020—from the 1619 Riots to the Great COVID Class War. Solzhenitsyn mused: “Should one point out that from ancient times declining courage has been considered the beginning of the end?”

Perhaps political virtue “is always one generation away from extinction.” But by the same token, political vice is always one generation away from correction. The next generation must always be educated. How, then, can we reverse the decline in courage for future generations of Americans? What would an education in courage look like? To begin with, it would not be an education of the mind only. It would be true paideia—training in both body and soul.

Physical Education for Body and Soul

As important as good instruction in history, philosophy, and theology are, book-learning itself is insufficient education for free citizens. A human person is an integrated union of mind and body, not a ghost in a machine.

The books themselves—or at least the best of them—agree. Plato’s Republic describes the education of “guardians,” warriors who will selflessly serve their city, acting like well-bred sheepdogs who guard the flock from wolves (a catalogue of human types memorably summed up in the 2014 film American Sniper). Plato summarizes this with what is clearly a traditional Athenian definition of education: music—meaning all the cognitive arts presided over by the Muses, including mathematics and poetry—trains the soul. Gymnastics trains the body. These two halves are inseparable and mutually reinforce one another. Too much music and not enough gymnastics makes students excessively soft. The guardians must be fit—not only physically tough, but psychically tough as well.

Exercise of the body cultivates “spiritedness” or thumos: that part of ourselves by which we feel a sense of self-worth, by which we get angry and push back and stand up for ourselves (and others) when we are offended. Morally, spiritedness is the part of the soul with which what is higher (our reason) may rule what is lower (our desires). As C.S. Lewis pointed out, “it is by this middle element that man is man: for by his intellect he is mere spirit and by his appetite mere animal.” An education that only tries to cultivate the mind risks making “men without chests,” faux intellectuals whose “heads are no bigger than the ordinary: it is the atrophy of the chest beneath that makes them seem so.”

Flabby bodies and flabby souls are bad for the student and bad for the country. Politically, spiritedness is the part of the soul without which a citizen becomes a mere subject. Citizenship—the ability to rule and be ruled as an equal, rather than beg and be rewarded as a servant or client—requires the “manly firmness” displayed by the American revolutionaries who opposed the king’s “invasions on the rights of the people.” It requires the thumos of the minutemen memorialized by Emerson in his Concord Hymn: “Spirit, that made those heroes dare, / To die, and leave their children free.” Spiritedness equips citizens to act upon their duty to secure their rights, and the rights of others, when they are threatened. It is the seat of courage in the soul, that which moves us to act despite the danger.

There can be no restoration of American citizenship without a restoration of American spiritedness. And physical or “gymnastic” education is necessary to cultivate the spirited and courageous part of the soul.

The Catholic college where I teach addresses these issues through its outdoor and horsemanship program. Freshman year begins with a 21-day backpacking trip in the Rocky Mountain wilderness. Freshmen face a new challenge before the spring semester, returning to the wilderness for a week in the Wyoming winter. And throughout their four years, in lieu of fall and spring breaks, our students go on “outdoor weeks”: kayaking, rafting, canyoneering, mountain biking, rock climbing, ice climbing, skiing, and more.

Moreover, every student is introduced to horsemanship (about which another great Greek philosopher had something to say). Horsemanship requires that the rider discipline his own emotions, humbly understand another creature’s distinctive nature, and cultivate the virtues of leadership. At its best, horsemanship is not only a fun pastime or a useful skill for the rancher; it is an integral part of a civic and liberal education, requiring a horseman who masters his passions so that he may exercise non-despotic rule over another ensouled, high-spirited animal.

Our therapeutic culture refers to a neutered form of spiritedness when it speaks of “self-esteem.” The cultivation of excellence, including physical excellence, elevates self-esteem from an unstable and subjective mood to a well-founded and objective state of the soul. Self-esteem at its best results in courage to stand up for oneself and others. The young men and women who go through our course of liberal education cultivate genuine and well-deserved self-esteem. The foundations for this are laid in their gymnastic education—when they lead their peers to summit a 12,000-foot mountain or lead their horse through a quadrille.

A liberal and civic education should cultivate not mere knowledge of the virtues, but possession of the virtues themselves. The virtues are acquired through repeated practice. And what better way to practice the virtues than by ruling oneself and ruling others in a way that is fitting, even required, of free men and women?

Courage and Freedom

My college’s wilderness trips address another good that contributes to liberal and civic education: unmediated encounter with the natural world. The beauty of the outdoors is enjoyable enough to recommend itself on its own terms to everyone. But that very beauty, and the wonder it evokes, suggests that it must be understood with reference to something higher to itself—God, whose “First Book,” as St. Augustine teaches us, is nature itself.

The wilderness, approached as part of a gymnastic education, offers concrete obstacles and objective limitations to the student. The mountain is this high, the possible routes to the top are this many and each is like this or like that. This river is this deep, flowing this quickly with these rocks and sandbars and these twists and turns. That cloud will explode into a thunderstorm—or won’t. It’s not up to the student, or to the teacher, or to “society.” Failure or success results from the student’s ability or inability, preparation or lack of preparation, vice or virtue—and, to some extent, from chance.

Our ordinary experience of the artificial, constructed world tempts us to believe we are gods who can create the world to suit our needs and desires‚ then create or re-create ourselves according to our whims. The wilderness, experienced immediately and directly, shatters such illusions. This opens a transcendent vista to the student, who may marvel at that which is greater than him, and thereby be reminded of that than which there is nothing greater. The experience of objective limitations in the wilderness also habituates the student to testing his strength and capacity against such limitations.

A gymnastic education may be adopted and adapted by anyone, anywhere. The natural limitations of physics and one’s own body may be experienced in any home—even when one’s own body is the only weight available. The wilderness may be more or less accessible to you, depending on where you live and what resources are at your disposal. But the world, the whole world, is charged with the grandeur of God, and even if you do not have the opportunity to practice ruling others in a liberal manner, you will always have yourself to rule.

Gymnastic education has fallen into contempt. To be sure, the goods that it directly addresses—physical fitness and health—are not the highest goods for man. But they, and the virtues more immediately rooted in the body (courage and moderation), are not mere necessities that must be secured for the sake of what is higher. Without a well-cultivated spiritedness and well-practiced courage, vices of all kinds—moral, intellectual, and social—proliferate. Cowardice, a vice especially tempting to those who live comfortably, is a political problem. A cowardly citizenry is no longer a citizenry, but a mass of subjects waiting to be ruled. There can be no liberty, individual or political, without courage. There can be no courage without cultivating spiritedness. And the surest way to cultivate the spiritedness of ourselves and our fellow citizens is through a renewed education of the body.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Human bodies are irrevocably either male or female. Attempts to change that are recklessly destructive.

Finding a middle ground between Kardashian bod and blobby positivity.

Honor and beauty, not economic incentives, can bring birth rates back up.

Antagonism to Big Health is making unlikely allies of crunchy moms and right-wing trads.

Our humanity must reassert itself over our technological power.