The biomedical security state.

Wisdom Before Science

Even knowledge needs restraints.

Aaron Kheriaty has done—is doing—his part as an American citizen to address the COVID epidemic and the reconfiguration of American life for which it served as pretext. He did his job as a psychiatrist at U.C. Irvine, tending to patients sick with COVID. He eventually caught the disease, isolated according to procedure, and recovered. He did his job as an ethicist at Irvine, helping to formulate reasonable policies with regard to the best uses of the medical resources available during the period when we were all very worried about overcrowding in hospitals. And he did his job most of all when he opposed university vaccine mandates for their invasive illogic. He stood up for his and every other American’s rights by going to federal court—for this U.C. Irvine, which he sued, fired him.

Kheriaty did not stop there. He has since been involved in giving testimony to legislatures about the evils of COVID tyranny and in various organizations and marches to stand up for our rights. He has written for everyone from the WSJ onward, denouncing tyranny in the most reasonable and professional manner. And he has written this book, The New Abnormal, to further the endeavor of educating the citizenry and inspiring Americans to fight against this evil, lest it be repeated.

This spring, on a related topic, I wrote in this publication about the beginning of courage: “COVID is an elite attempt to nationalize cowardice. The conflict is fundamental and it is, first of all, a conflict about manliness, about whether we will allow ourselves to be, as we used to say, pushed around—ruled despotically.” I had in mind men like Kheriaty. We need more of them, and we need to learn to join together for action.

In addition to his professional ethics and public spirit, Kheriaty offers us the reflections of Christian humanism on the technological tyrannies of the 20th and 21st centuries—his thinking is guided by impressive writers like Giorgio Agamben, Augusto del Noce, and, of course, C.S. Lewis, who want to defend the human person against the impersonal power of modern institutions. These institutions, callous when not outright cruel, have come increasingly to see humanity as a problem to be solved.

Kheriaty defends science itself, both in its ambitions and its achievements, from the scientism which has become the favored weapon of tyranny in our times. Science, he insists, has an in-built modesty, since its results are only provisional and can always be improved on. Science is in this sense humanistic—it’s an attempt to help us fend off death by disease or however many other troubles. But to do so it must be governed by our political understanding of our own good. After all, the doctor may repair my broken leg or save my life with an organ transplant—but neither he nor any other scientist can decide what organs make up a human body or how many legs I should have. Something pre-scientific must be in control of the achievements of science; we have to somehow know what’s good for us if we are to judge what scientists do in our name.

The opposite situation now obtains in our world, however: Scientism is a shrill, hysterical tyranny—obedience is demanded of us in word and deed, with our livelihoods at stake if we refuse or sometimes hesitate, and we are further morally demeaned by accusations of wanting our fellow citizens to die. At the same time, we do not know who makes what decisions at what level—who actually rules in this country? Who is responsible for any decision that might greatly affect us? What is going on?

It’s not enough to say that the bureaucrats of public health, national and international, are unelected rulers. We have to add that the bodies which make decisions and their procedures are hidden from our view, too. This implies that our rulers do not believe we are human—we do not have what Aristotle assured us we do have: a political and rational capacity to reason deliberatively together and act to a common purpose.

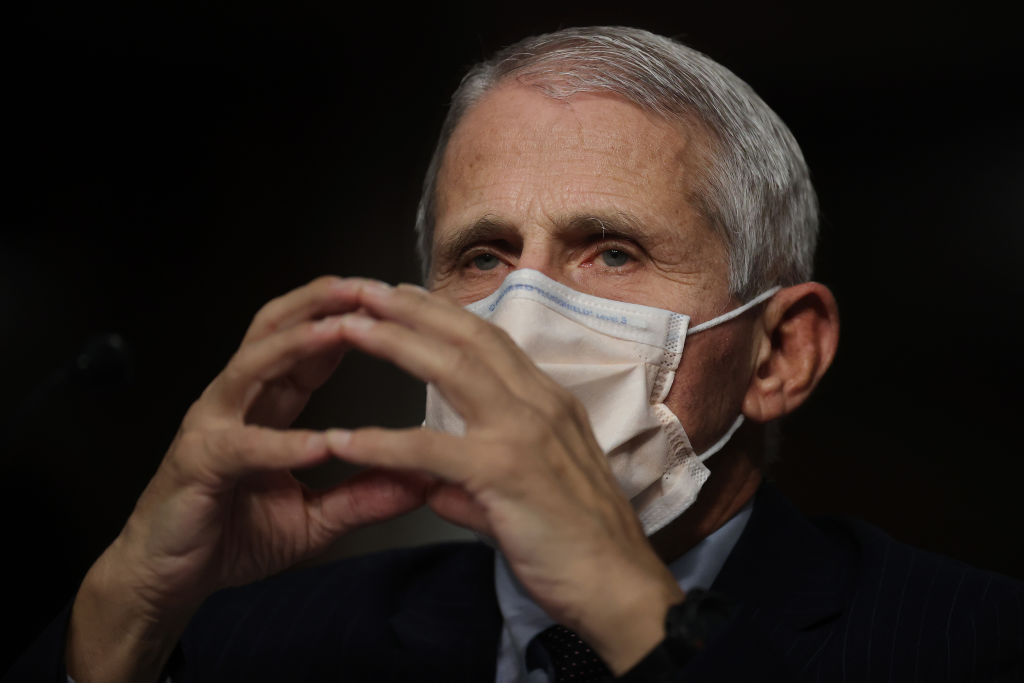

We did not govern ourselves through the panic and pandemic. We were not prepared for such an attack on our rights, and we did not know to whom to turn or how to defend ourselves. Trump was no better able even to stop Fauci than Biden is. Partly, that’s because there is a kind of scientific authority that our elites impose on us without our ability to fight it off. We need elites of our own who don’t obey this scientism and who know how to deal with every aspect of administration, politics, and public opinion to help us overcome our current weakness. Potential leaders who read Kheriaty’s account of the spiritual and organizational tyranny expanding around us should not just feel edified: they should feel inspired to get to work.

We need to reckon with the possibility that one branch of science—our medical research—created the disease from which another branch—public health authorities—want to protect us by tyrannizing over us is. This raises the fundamental question: Is knowledge itself tyrannical? Does knowledge applied to human affairs turn inevitably into an empire administered ruthlessly and which destroys freedom?

If we are to answer this question in the negative, it follows there must be something that rules over even knowledge—some moral goods in service of which knowledge is sought and applied. Modern scientism, by contrast, proposes to encompass all. Wherever we turn we find another one of its powers at work or another class of people who claim scientific authority. This is not merely a political danger but a spiritual one.

It’s one thing to suffer from political decadence but another to be denied the humanity on the basis of which we can organize politically. The only way forward is actively confronting classes of elites who, in embracing science, technology, and institutional rule over America from childhood, grow into tyrannic adults. They are unfit to be our “first citizens,” votaries instead of a cult of their own annihilation—so long as it’s ours first, because they hate the one thing they share with us, our troubled humanity.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Appeals to “The Science” increasingly come from political actors whose real concerns lie elsewhere.

We will have to pick one.