The civic framework of freedom.

Liberty’s Limits

The indispensable political framework of rights and freedom.

Many thanks to Emina Melonic, Will Morrisey, Nathan Pinkoski, and André Kespian for responding so thoughtfully and suggestively to the excerpt from my new book on Pierre Manent and Roger Scruton. The excerpt is entitled “Rescuing Rights from Themselves,” and each respondent shares my broad forebodings about what I, following Manent, call “the ideology of human rights.” Those who propound this self-radicalizing conception of rights have little or nothing to say about the ends and purposes of human freedom. Their philosophical anthropology is remarkably shorn of content and is linked to no substantial or compelling account of the human soul or human person. This faux appeal to ever-expanding rights is perfectly compatible with a denial of free will and moral agency and with the fictive categories (i.e., class, race, and gender) that dominate ideological politics today. In this rendering, rights are severed from responsibility and self-limitation and always aim to “liberate” and “emancipate” the individual from the social and political framework of human freedom. The ideology of human rights is thus inseparable from what Scruton liked to call “the culture of repudiation,” where negation always takes precedence over affirmation. A destructive nihilism haunts it from beginning to end.

This ideological deformation of rights sunders the abiding connection between the dead, the living, and the yet to be born which, as Edmund Burke so eloquently pointed out, is the very hallmark of civilized existence. Aiming to “empower” the individual, to free him or her from all oppressive bonds and obligations, this parody of liberty paradoxically leaves him prostrate before tyrannical ideological minorities (i.e., the Woke) and a collectivist state committed to a deeply coercive “emancipatory” project. By undermining the social framework of freedom, this cultural/political project strikes at the integrity of the soul itself. As I attempt to show in Recovering Politics, Civilization, and the Soul, Pierre Manent and Roger Scruton stand out among contemporary thinkers for their deeply thoughtful and courageous efforts to reconnect freedom to a rich account of the ensouled human person as a responsible moral agent, as a citizen and patriot who is more than a bearer of self-referential rights, and as a guardian and caretaker of an imperfect but ennobling civilized inheritance that is well worth preserving.

In her elegant essay, Emina Melonic supplements my Manent-inspired analysis through her own thoughtful and poetic affirmation of the ties that connect true human individuality with truth and a freedom that is not coextensive with “disorder and chaos” in the soul and society. Like Scruton and Manent, Melonic fully appreciates that Communism annihilated human freedom precisely because it denied the human soul and the rich “human interiority” that flows from it. She nicely highlights the mutual reciprocity of freedom and truth, since the human soul withers when it loses its connection with these two precious goods. Such truth-affirming freedom needs a political realm, a “public space” as Hannah Arendt called it, so that men and women can “act in the real world”—a world marked equally by limits and possibilities rooted in the order of things.

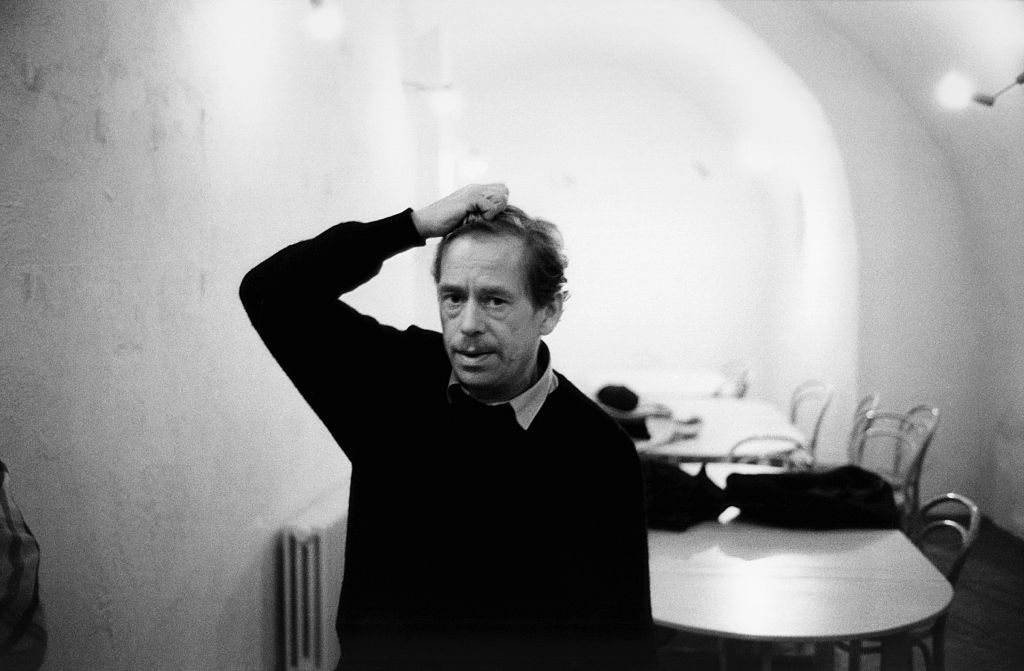

Recovering the “face-to-face encounter” (more a theme of Scruton’s than of Manent’s), Melonic reminds us that politics is also a call to service and not only or primarily an agonistic realm where we assert ourselves at the expense of others. Drawing on the writings of Václav Havel (and my own chapter on Havel in my recent book The Statesman as Thinker), Melonic demonstrates how ideological politics, by politicizing everything, paradoxically destroys the distinctive political realm which is so essential for human liberty and dignity.

Havel reminds us of the indispensability of courage to human freedom rightly understood. And as Melonic intimates, politics can never be radically severed from conscience in the morally fulsome sense of the term. It should be remembered that in his great “dissident” essays and his speeches and writings after 1989, Havel repeatedly tied the right of the human person to breathe freely to an uncompromising commitment “to living in truth,” not only as a weapon against decayed and decaying totalitarianism but as the prime gesture of the human person. Without a “metaphysical” affirmation of truth and responsibility (which are at the same time the most concrete of affirmations), goodness, decency, and ordered liberty wither away. Solzhenitsyn taught much the same thing.

The Bonds of Freedom

With impressive lucidity, Will Morrisey reminds us that “rights unfettered by natural law are also undefended by it.” It is of course theoretically difficult to reconcile “rights talk” with a more traditional affirmation of the standards and limits that stand above mere human self-affirmation. In a larger theoretical sense, rights clamor to be emancipated from natural and divine limits and restraints. That is their logic and telos. But as Morrisey insightfully shows, choice and consent must bow before authoritative standards of judgment if they are to have meaning at all. Without such standards, ostensibly “free” human beings are in fact left bereft, subject to moral and political isolation and powerless to defy a state that recognizes fewer and fewer limits on itself. Morrisey reminds us that in our own tradition, the Declaration of Independence nobly melded natural law and natural rights together in an unforced way. Let us not forget its deference to Divine Providence (and not just “Nature’s God”) and its stirring call for free men to put their “sacred honor” above our fortunes and our physical self-preservation if need be. The Declaration weaves together a respect for natural rights, a spirited opposition to emerging tyranny, deference to the Most High, and an ennobling call to sacrifice our comfort and fortune on behalf of liberty and national independence. It is marked by moral and civic high-mindedness that is anything but low or demeaning.

Nathan Pinkoski’s response shows an impressive familiarity with the thought of Pierre Manent. Manent is indeed a penetrating critic of the “depoliticizing” tendencies at work in late modern thought. The “emancipation” of the individual historically went hand in hand with the weakening of the corporate bodies or associations that stood between the state and an emerging civil society. But what happens when authentic political authority is “leveled” too? A political community that can no longer execute the most egregious murderers and criminals is a political community, a state, that has been cut off at the knees. Progressives in the Catholic Church, including the present pontiff, are already denying the legitimacy of “just war.” As Pinkoski puts it, such thorough-going humanitarianism “demolishes the reason for the state’s existence.” Rights run amok ultimately undermines the political framework that protects life and limb and the nobler exercises of human freedom as well. To “abolish” the state in principle is to abolish the framework in which rights and duties can be exercised outside of a pre- or post-civilizational “state of nature.” The best of ancient and modern thought can agree that liberty degenerates into lawlessness and chaos without a political framework that protects and coordinates the rights and obligations of citizens and human beings. They stand together against the new antinomianism.

Pinkoski is also exactly on mark when he suggests that “if pushed, Manent, like C.S. Lewis, would probably prefer to ground individual and communal self-defense” (i.e., capital punishment and the “right to bear arms”) “in natural law rather than in the early modern appeal to the state of nature.” But liberty, ancient or modern, is always “under law” if it is anything at all. That is something our contemporary antinomians have forgotten to their and our own peril.

André Kespian has perfectly captured “the art of conciliation” at the heart of Manent’s thought. American and English liberty was so stable and decent for so long precisely because the English-speaking peoples refused the absolute valorization of modern principles. The British refused to jettison monarchy, traditional jurisprudence, and the Protestant religion, while Americans remained attached to “associative life and religious piety” until quite recently. The French revolutionaries, in contrast, were what Alexander Hamilton called “fanatics in political science,” imprisoned by totalizing abstractions and overcome by a desire to begin everything anew in a surreal revolutionary “year zero.” Kespian artfully highlights the crucial role that free politics plays in preventing freedom from becoming the abstraction so beloved by modern intellectuals who seem to specialize in political irresponsibility.

Kespian is also right that rights should not be jettisoned in the name of moral and political relativism and a one-sided emphasis on historical particularity. But if rights are not reducible to universal rules, as he rightly argues, and must always be accompanied by prudence and a common-sense affirmation of the natural law, it is a mistake in my view to reject the “universality” of rights per se. They are not “nonsense on stilts” as Jeremy Bentham and Alasdair MacIntyre seem to believe. But their universality must be mediated by the wisdom of the statesman and the practical deliberations, the messy give-and-take, of practical political life. We do indeed need what Kespian calls a “a grounded individualism, wherein individual good is not to be found outside or against the common good.” That is the project of the liberal conservative tradition from Tocqueville to Manent and Scruton. Kespian lucidly summarizes one of Manent’s core theoretical and practical insights: “The individual pursuit of happiness can only have value and substance inside an authentically political framework, one grounded in the history and culture of a given nation.” One could not say it any better.

Carl Schmitt famously remarked that there is no such thing as liberal politics, only “a liberal critique of politics.” Pierre Manent begs to differ but only if free men and women have the fortitude to affirm the political, spiritual, and civilizational prerequisites of liberty rightly understood. The choice is ours in this troubled and confused time.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

True freedom means recognizing both human individuality and absolute truth.

How to keep modern liberalism from eating itself alive.

The debate over capital punishment illustrates two irreconcilable views of the nation.

Rights unfettered by natural law are also undefended by it.