The debate over capital punishment illustrates two irreconcilable views of the nation.

The Inner and Outer World

True freedom means recognizing both human individuality and absolute truth.

The concept of human freedom presents a unique and difficult challenge. There is no such thing as pure freedom, yet that doesn’t stop us from pursuing it—sometimes to a fault. The deep humanity in our urge to rebel is a double-edged sword: we assert our individuality against coercive forces, which we perceive as undermining and diminishing the singularity of a human person; we also unjustly mob together against authority because we hate hearing “no.”

Inevitably we fight over what freedom is and whose definitions hold sway. If freedom is simply the removal of constraints from the individual’s ability to act and judge as he chooses, then surely we are bound to fall headfirst into relativism. Just as truth can be perverted into a coercive tool (my truth, underwritten by my identity, overrides the basic order of reason and the shared understanding of reality), freedom too can become an occasion for relativism that only serves the imperatives of the narcissist and the crowd. To be free means taking personal responsibility—otherwise freedom would have no meaning, and most importantly, no relation to other human beings. One cannot speak about human rights without personal responsibility, either.

Reflecting on Pierre Manent’s work, A World Beyond Politics, Daniel Mahoney singles out important elements that run through concepts of freedom and rights. Rights, which are meant to be linked to citizenship and politics, are tossed around casually into today’s discourse only as an excuse to create disorder and chaos, both for the self and the society. (See, for instance, the current destructive obsession with so-called “trans rights,” which pervert both the human body and soul to rebel against natural and divine authority.)

Communism is, of course, among history’s best examples of what freedom is not. As Mahoney notes, “communism in every time and clime systematically violates the natural law. Its newfangled ‘ideal’ twisted what is noble, just, and fair, beyond all recognition . . . the communist regime could never honor basic human needs.” Communism did not and does not take into account the human soul and its singularity. Since freedom is a balance between the irreducible uniqueness of the human individual and the immutable existence of absolute truth, perversions of freedom will always elevate one of those two things at the expense of the other. Communism annihilated freedom by denying the human soul. This coercion inevitably turned into bureaucracy, whose very definition and existence depend on denial of human interiority.

One of the most significant points that Mahoney makes is the existence of “the radical atomization of society,” which—paradoxically enough—renders politics apolitical. Politics cannot exist without freedom, that is to say, the public square in which people are free to express their thoughts. Politics also depends on the existence and acknowledgement of public and private spheres. To be sure, these are separations, but they are not fragmentations of the mind or the soul. As Mahoney notes, “we are obliged to live freely but in light of the truth.”

How, then, can we be political and free? Certainly, we cannot allow politics to be the only defining factor of who we are as human beings. Otherwise, we will merely turn ourselves into ideological data that keeps getting optimized until the feedback loop destroys any remnants of our uniqueness and dignity.

To be engaged in politics is to be in relation to politics. Man does not make decisions only for himself: the consequences of any decision will affect others as well. We are relational, and this is one of the things that defines our humanity. There are, of course, different levels of this relationality. I can “relate” to my cup of water as I hold it and drink it. My acceptance of the cup’s reality, external to me and in some sense beyond my control, is a key component of true freedom: I have to live in the real world to act in the real world.

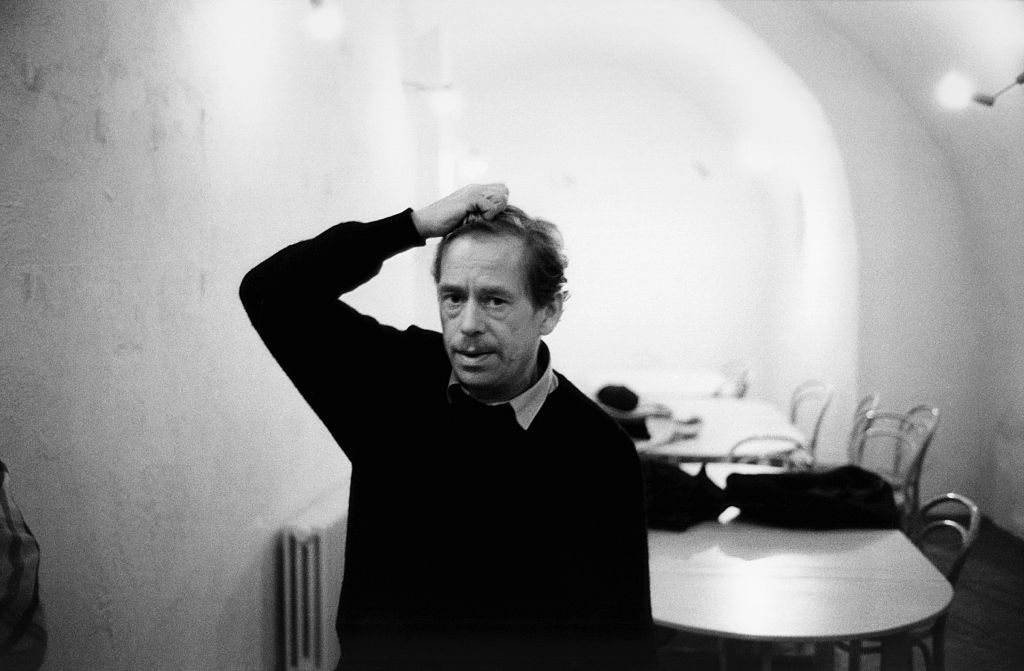

This situation becomes more complex, and more urgent, when the object of my relation is also a subject in his own right: when the two people in relationship are both unique individuals with agency. Relationality in politics means affirmation of human dignity and acknowledgment of a face-to-face relation. We cannot build truly political lives for ourselves without directly recognizing this kind of metaphysics. Nobody knew this better than the Czech statesman Václav Havel. When the Communist Party’s secret police imprisoned him, Havel read the work of philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, whose philosophy is grounded in the face-to-face encounter, the rejection of Heidegger’s “Being toward Death,” and the primacy of ethics over aesthetics. For Levinas, the human face is the constant call to serve.

Havel was greatly taken by this. He is most likely the only statesman in modern history who was also a playwright and a philosopher—“in important respects,” as Mahoney observes in The Statesman as Thinker, “the model of a humane, liberty-loving ‘philosopher-king’.”

Levinas’ philosophy sparked something inside of Havel. In a letter to his wife, Olga, dated August 21, 1982, Havel wrote: “We live in an age in which there is a general turning away from Being: our civilization, founded on a grand upsurge of science and technology, those great intellectual guides on how to conquer the world at the cost of losing touch with Being, transforms man its proud creator into a slave of his consumer needs, breaks him up into isolated functions, dissolves him in his existence-in-the-world, and thus deprives him not only of his human integrity and his autonomy but ultimately any influence over his own ‘automatic responses.’”

This statement alone affirms the dangers of atomization that Mahoney mentions in his essay. Without a recognition of human interior life and dignity (both our own and others’), there is no chance that we can live as free people. This is how the rise of apolitical or ideological politics happens. Paradoxically, when we live our lives beyond politics, we become authentically political. Our dignity and thought are working in concert, and we choose not to allow ourselves to be coerced into something which goes against our conscience.

None of this is easily achievable. To be free actually takes courage, because freedom is inextricably linked with responsibility. This is why someone like Havel was still free in a metaphysical sense despite being literally in prison. It takes fortitude to reject collectivism at any cost and be willing to stand alone.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

How to keep modern liberalism from eating itself alive.

The indispensable political framework of rights and freedom.

The civic framework of freedom.