Pious identitarian elites punish you for their guilt.

The Contradiction at the Heart of Identity Politics

Our adversarial multiculturalism urges majority groups to disown their identity and minorities to cling to theirs.

David Azerrad has written an incisive, deeply-researched essay which skewers the dominant New Left ideology of American high culture.

Drawing on an extensive intellectual history, he traces this creed back to the black, ethnic, women’s, and gay liberationist movements of the 1960s, demonstrating how their avatars adopted a Manichaean “us-versus-them” worldview that demonizes white straight men. Azerrad shows the problems did not begin with the post-2014 campus antics catalogued by Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff but begin in the 1960s.

This is right, but in my book Whiteshift, I trace the roots of this back still further, to the fusion of Left wing and modernist (or anti-traditionalist) currents in Western thought that Daniel Bell chronicled in his Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (1976). This Left-modernist fusion had congealed as early as the 1910s among a select group of bohemian intellectuals who not only rejected their own culture, but essentialized and romanticized the Other against Anglo-Protestant domination. In the Greenwich Village of 1916, “Young Intellectuals” like Randolph Bourne derided their WASP co-ethnics as parochial and uninteresting compared to white ethnics like the Jews, with their rich traditions, or African-Americans, with their jazz and expressive ethos. A few decades later, the Beats would repeat the same formula; across the Atlantic, in post-1930 England, George Orwell would note that most English intellectuals were ashamed of being English and incessantly criticized their country’s traditions. Today, WASP has morphed into ‘white’ and the tone has grown still sharper.

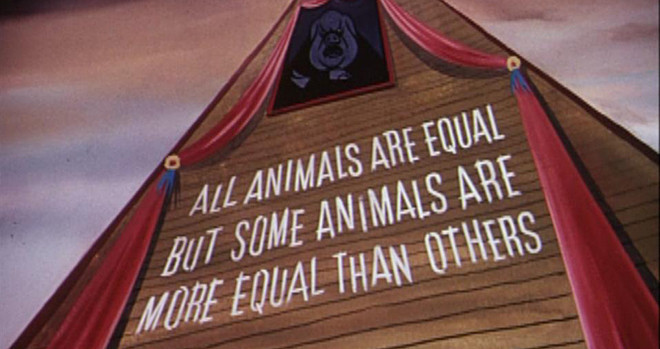

For Bourne, the only solution was for WASPs to reject their ethnicity and become cosmopolitans while minorities ‘stick proudly’ to their faith and culture. This contradiction—between urging majority groups to disown their identity and minorities to cling to theirs—lies at the heart of multiculturalism. It reflects a paternalistic white-majority elite perspective: guilt over unearned privilege combined with a desire to assert cultural superiority by adopting a more sophisticated outlook than one’s country cousins. What Bell termed the new “adversary culture” of the twentieth century sprang from these loins.

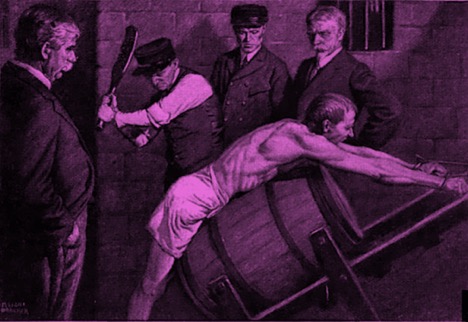

What has occurred since the 1960s is a scaling up: as Bell notes, the adversary culture migrated from the small circles of intellectuals Orwell wrote about to “the giant screen” of television and the mass higher education system. It has subsequently permeated K-12 education, Hollywood, large corporations, parts of the media, mass culture, government and the judiciary. Now that it has marched through the institutions, what was supposed to be a rebellious but marginal critical voice has become the dominant force in the culture: not a tolerant establishment but a punishing inquisition that casts out heretics like James Damore or Bret Weinstein.

Influenced by the white adversary culture, the minority activists Azerrad critiques have in turn energized it by playing the role assigned to them—that of the terminally oppressed. White leftists applaud. “More, more,” they urge. But minorities who play this role—figures such as Ta-Nehisi Coates—don’t represent the views of the minorities on whose behalf they claim to speak. Representative survey data I analyzed for my recent New York Times piece repeatedly pulls back the curtain on such claims, revealing that most minorities do not support racial quotas, do not blame their group’s lack of progress on racism, and are much less enthusiastic about diversity and open borders than white liberals.

I gently part company with David on some things.

I think the rise of national populism in the West is driven more by a desire for slower ethno-cultural change and stability than a yearning for meritocratic, individualistic civic nationalism. Without the challenge of fascism or communism, there is little chance of a nation unifying around the western values of liberty and democracy. Calling these “British values” or “the American Creed” cannot replace the importance of ethnicity when countries are undergoing rapid demographic change or there is group inequality. These universal tenets are important to defend, but cannot necessarily compete with other identities in providing meaning in everyday life.

Going forward, national identity needs to allow different groups to read their scripts into the national epic. This means what I term multivocalism: tolerating conservative whites who celebrate the settling of the West as part of their Americanism as well as progressives who see the nation as multicultural—so long as neither tries to shut down the other and impose their version of the national story on everyone. Each may read what they want into the flag, attaching in their own way.

In this sense, I think identity has a role to play in politics. We cannot expect blacks to have eschewed appeals to black identity in mobilizing against Jim Crow. So too Asians contesting affirmative action at Harvard or, more controversially, ethnic majorities seeking to slow the pace of large-scale immigration in order to permit assimilation and reduce communal disorientation.

I agree with David that the case should rest on universal principles and not special group rights, but a universal principle is that it is legitimate to be attached to a group and to seek to mobilize it for a principled stance. How our group is faring does affect us, even if we as individuals (i.e. rich blacks) may, by degrees, be unaffected by some disadvantages.

Haidt and Lukianoff distinguish between a “common enemy” version of identity politics in which a virtuous “us” is contrasted with an evil “them,” and a “common humanity” identity politics based on looking out for “us” while holding no animus toward “them” and making compromises and sacrifices to optimize the good of the whole nation. This means a moderate identity, balanced by the common good.

Yet the left, following the tortured logic of Randolph Bourne, has opted to push a maximalist “common enemy” version of identity politics for minorities while denying even a “common humanity” identity to whites or men. Most minorities reject this. But conservative whites are being pushed ever harder to react to the gross unfairness of this dominant form of identity politics by voting for national populists.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

We need courage to replace the politics of special privilege with the politics of equal justice.

Identity politics offers disenchanted radicals one more shot at utopia.

Identity politics legitimizes inequality and the moral superiority of its elite.

America can't stand the retributive injustice of identity politics.