Pious identitarian elites punish you for their guilt.

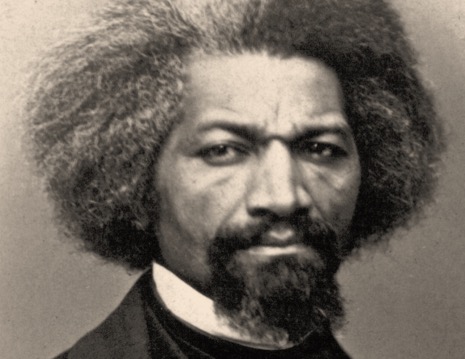

Rising to Frederick Douglass’ Challenge

We need courage to replace the politics of special privilege with the politics of equal justice.

The genealogy of ideas is important. Without dissenting from the insightful and persuasive account that David Azerrad gives of the essential features (and dangers) of identity politics, I’d like to add a couple of twists to his analysis of its origin and development.

Azerrad rightly highlights the extremely simple race-based calculus of Malcolm X who, as a minister of the Nation of Islam, argued that all whites were devils and all blacks were their victims. Even after breaking from the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X continued to say “I’m not an American. I’m one of the 22 million black people who are the victims of Americanism.” Azerrad concludes that “a common enemy ultimately proves to be the real basis of identity politics.”

However, there is a consistency in the early Malcolm X that is absent from our current version of identity politics. As a radical black nationalist, Malcolm X wished to separate completely from America. He had no expectations of America and hence made no demands. Instead, he sought to convince his fellow blacks of their irremediable alienation from the land of their birth. His solution was black nationalism. Interestingly, he presented the American Revolution as a model of sorts. Claiming that the American Revolution was white nationalism, he called for a Black Revolution that would acquire land and independence (by bloodshed if necessary). Thus, although Malcolm X describes blacks as “victims of America,” he doesn’t formulate a domestic politics of victimization, but rather a militant and separatist politics of pride and racial assertion.

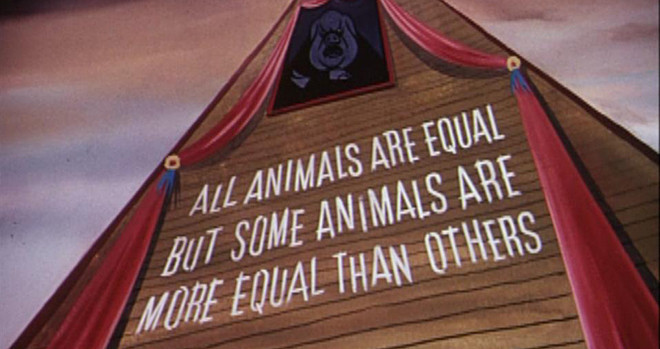

The cachet (and cash value) of victim status emerged only with the “mainstreaming” of Malcolm X by activists who were not willing to embrace all-out black nationalism. Black nationalism was transformed into a movement that sought black power from within American society, leading to the combination that Azerrad calls paradoxical and problematic—successfully extracting concessions and benefits while continuing to insist that America is white supremacist to the core.

In her essay “Refusing to be a Victim: Accountability and Responsibility,” bell hooks (she intentionally lowercases her penname) argues that the black struggle took an unfortunate detour when civil rights leaders in the late 1970s started to compete with and imitate the strategies of white upper-class feminists.

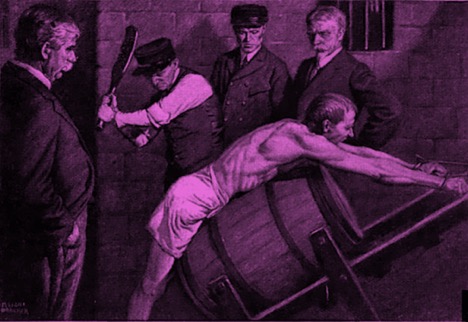

According to her, “the rhetoric of victimhood worked for white women”—when you are sleeping with your oppressors, special pleading can be advantageous. Black activists adopted the mantle of victimization as well, in part because it was less threatening (and in fact quite flattering) to the white male power structure. Azerrad acknowledges the role played by the white guilt of the liberal elite in inviting and sustaining this perverse dynamic.

Shelby Steele diagnosed this power play based on victimization and the liberal response of cheap tokenism (affirmative action quotas and now diversity) in his 1990 book The Content of Our Character. Interestingly, hooks speaks quite favorably of Steele, agreeing with him about the ultimately disempowering effects of seeking power by this wheedling route. At the same time, she vehemently disagrees with his view that racism, while still present, has substantially lessened. She speaks not of racism but of “white supremacy”—a term that indicates her evaluation of the systemic nature of the problem and inspires her call for the dismantling of structures of domination. As so often, however, there are substantial points of agreement, especially a stress on self-reliance, between conservatives like Steele and militants like hooks.

The danger of this detour into the politics of victimization was understood more than 150 years ago by the great Frederick Douglass. In a speech entitled “What the Black Man Wants,” given shortly before the end of the Civil War, Douglass noted that “the American people are disposed often to be generous rather than just…. What I ask for the Negro is not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice.”

At the end of his essay, David Azerrad explains why people of good-will find it difficult to resist the “powerful pull” of identity politics. It places us in a bind by telling us we must either embrace identity politics or stand condemned as “callously indifferent.” Azerrad exposes this as a “false choice,” but he also says that it operates on us by appealing to “our sense of justice.” I think, in fact, that the demands of the identitarians don’t target our sense of justice; they appeal instead to our pity and compassion. Justice is made of stricter stuff.

Sad to say, in an era that is so relentlessly subjective and sensitive, it is very hard to make the case for equal justice under the law. More Americans, black and white, need to find the courage to do so, as David Azerrad has. But I suspect that Americans also need to think more seriously than we have about what a single shared standard of justice would actually demand of us. If the example of Frederick Douglass tells us anything, it is that the politics of equal justice may require a more far-reaching societal transformation than the politics of special privilege (which, as Azerrad’s mention of Thrasymachus and Polemarchus shows, is pretty much politics as usual).

In an 1889 address entitled “The Nation’s Problem,” Douglass warned blacks against organizing on the basis of race pride, since that would inevitably strengthen the race pride of whites—the very thing, Douglass says, we are fighting against. In Azerrad’s discussion of the backlash against identity politics, he warns of a possible “rise of white identitarianism.”

I agree that this is a real danger. However, I think that Azerrad misallocates the blame when he warns that, if it does happen, “the identitarians will have actually produced that which they claim to oppose.” They may re-awaken the dragon, but I’m pretty certain that something like white identitarianism has been present all along (from Jefferson’s racial theorizing to Stephen Douglas’s assertion that our government was founded on a “white basis” to the segregationists who ruled for a century after the Civil War). Here’s Douglass on the topic of white identitarianism:

The poorest and meanest white man, drunk or sober, when he has nothing else to commend him, says: “I am a white man, I am.” We can all see the low extremity reached by that sort of race pride, and yet we encourage it when we pride ourselves upon the fact of our color. I heard a Negro say: “I am a Negro, I am.” Let us away with this supercilious nonsense. If we are proud let it be because we have had some agency in producing that of which we can properly be proud.

Rising to Douglass’s challenge means that race—or any of the other given identities that constitute the ground of identity politics—ought not to be a bare source of pride or power. Americans must figure out how, both as individuals and as a collective, to acknowledge the injustices of the past and present while taking legitimate pride in our national achievements and recommitting ourselves to our founding principles.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Identity politics offers disenchanted radicals one more shot at utopia.

Our adversarial multiculturalism urges majority groups to disown their identity and minorities to cling to theirs.

Identity politics legitimizes inequality and the moral superiority of its elite.

America can't stand the retributive injustice of identity politics.