We must not ignore our extraordinary blessings.

Last Stands

War underwrites peace, and heroic sacrifice enables civilization.

Our friend Michael Walsh’s Last Stands: Why Men Fight When All Is Lost, is a needed antidote to the fatalism that plagues the western world in response to its own suicidal urges. As waves of populist movements increasing reveal the growing unrest of the citizens of the west against their own leaders, potential new leaders who might stand up in this era of decadent follies remain inactive not merely on account of fear, but despair. After all, it seems every major institution is corrupted. It seems we are fated to decline.

There is no better meditation to combat such despair than the nature of warfare. In a time of relative peace, the “doomerism” of today is silly. There is still much farther to fall. But even after descending into the inevitable violence that awaits after precipitous cultural decline—the violent human “norm” that few living now remember—all is never lost. Meditating upon warfare prevents us from childishly feeling sorry for ourselves and turns our gaze back to what needs doing. Last stands are the hallmark of heroism. And heroes are what an increasingly desperate world needs now. –Eds

It is fashionable today to regard war as the exception and peace the rule, but a simple glance at an unexpurgated and unbowdlerized history of the world—ancient or modern—quickly shows the essential nature of bellicosity and its importance to the survival of and, ofttimes, the advancement of the human species. War, or the specter thereof, is the principal means of scientific advancement, of territorial expansion, and of the defense of those personal, social, and political elements a society holds dear.

Every age, it seems, yearns for peace but—heeding the old Roman maxim, Si vis pacem, para bellum—prepares for war. This is no less true today than it was in the time of Vegetius in his famous tract, De re militari from the fourth or mid-fifth century A.D. The history of the West, from the end of the Roman Empire to the present day, attests to the truth of the observation. Just when we think that the great geopolitical issues of the day have been settled by force of arms, along comes Clio, the Muse of History, to remind us otherwise:

England has now been blest with thirty-seven years of peace. At no other period of her history can a similarly long cessation from a state of warfare be found. It is true that our troops have had battles to fight during this interval for the protection and extension of our Indian possessions and our colonies; but these have been with distant and unimportant enemies. . . . There has, indeed, throughout this long period, been no great war, like those with which the previous history of modern Europe abounds. . . .It would be far too much to augur from this, that no similar wars will again convulse the world; but the value of the period of peace which Europe has gained, is incalculable; even if we look on it as only a truce, and expect again to see the nations of the earth recur to what some philosophers have termed man’s natural state of warfare.

—Edward Shepherd Creasy, The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World: From Marathon to Waterloo (1851)

Thus the view from mid-nineteenth century England, with the corpse of the Little Corporal safely entombed, breathing well-deserved lungfuls of fresh air devoid of gunpowder and the stench of rotting flesh and emptied entrails after the tumult of the Napoleonic Wars. And yet the preambulatory conflict of the Franco-Prussian War was only two decades in the future, and the unimaginable horrors of the First World War were already stirring in the souls of the artists, writers, and composers who could sense the slouching advent of the murderous beast but were powerless to stop it. As it turned out, the Treaty of Paris in 1815 was simply a caesura, the briefest pause in the historical record, before the harvest of death continued anew. Nothing, it seems, can stop the Kantian categorical imperative.

Because war’s price is too terrible to contemplate rationally, diplomacy has emerged over the centuries as a preferable alternative to physical conflict, and yet when diplomacy fails, war nonetheless breaks out. (The reverse is almost never true—except when the side that is about to lose begs for terms, almost always refused.) And then, men whose fallen fathers are still freshly in their graves, their widows still in weeds, their children barely out of knee pants, once more present arms and take to the battlefields, confident that their sons will willingly follow them into the smoke and haze and dust of death.

Why? Few are overtly in favor of war, and yet it has been a part of the human condition as long as there have been men to fight it. Indeed, some men thrive on it, and some require it in order to realize their passions and destinies. In American history alone, Washington was elevated by it; Grant was relieved from alcoholism and obscurity by it; Patton was transfigured by it and, when it ended, disappeared along with it. Some of history’s greatest figures saw it as an opportunity, but more often others regarded it as a sacred duty, a moral obligation. The proper use and management of armed might is one of the themes of Machiavelli’s The Prince: “Where there are good arms there must be good laws . . . whoever has good arms will always have good friends.”

How retrograde, how antique to our modern ears this all sounds. And yet it is quintessentially male, the inherited patrimony of one of the two sexes, and the most fundamental defense mechanism against the loss of home and hearth and, most important, progeny. For war is at root a masculine engagement, undertaken on behalf of females and children—in large measure to win and protect the former and to ensure the survival of the latter—a truth not lately much told or acknowledged. Children, once the future of a society, are now seen, in the right-thinking quarters of the postindustrial and sumptuously feminized West, as a burden both economic and social; women are regarded by some as fully capable of holding their own in any contests with men, whether mental, emotional, or physical, without any distinction or allowances; and as for men, well, the sooner they disappear into the dustbin of history, the better. After all, as the antiwar slogans of the 1960s put it, “War is unhealthy for children and other living things.” And who, historically, has fought—started, won, lost, or finished—wars?

We tend these days to think of war—when we think of it at all, so remote has it become—in near-bloodless terms, a luxury we ought no longer to afford. It has become an embarrassing relic of our past, something at once uncivilized and unnecessary. Although the United States has been engaged in a near-continuous series of wars, large and small, since the First World War, and has been embroiled in European and international affairs for even longer, war—with the notable exceptions of the Revolution, the War of 1812, and the Civil War of 1861–65—has largely avoided these shores. And that last war was the bloodiest in our national history, a cataclysm so powerful that its social and political effects are still being felt today.

It is, however, a war we honor. It was a war to save the Union and free the slaves, a war that pitted brother against brother, father against son, fought in essence in the short distance between Washington, D.C., and Richmond, Virginia, a war that cost more than 600,000 lives in a country numbering at the time only 31 million souls. It was a war—“a great civil war,” in Lincoln’s famous formulation in his Gettysburg Address—worth fighting and winning. “We Are Coming, Father Abraham, Three Hundred Thousand More,” went the poem by James S. Gibbons, set to music by America’s first great composer-songwriter, Stephen Foster, in 1862. Men and boys from Maine and Michigan shouldered arms to kill men and boys from Virginia and Alabama because the cause was worth it—no matter what the price.

This is, by any standard, the very definition of heroism. (The word derives from the Latin for “illustrious man” and, even earlier, from the Greek for “demigod,” with the added nuance of “defender” or “protector.”) War has always been elemental, involving spears and swords, clubs and arrows, cannonballs and canisters, all instruments of death. In the great battles of the past, armies clashed with the express purpose of slaughtering each other until one had had enough and surrendered, fled, or simply gave up to be butchered in the field like cattle. Hunger and thirst both took their toll, as did diseases against which there was no effective treatment or cure. When their ships were rammed, the oarsmen died and the men above decks were tossed into the sea to drown. Once hostilities were offered and accepted, as in Greek and Roman times—generally after a day or two of maneuvering around the battlefield for maximum tactical and operational advantage—the conflict was waged to its conclusion, which was more often than not decided on a single day in one location.

The pitiless brutality of it is literally beyond modern imagination. Heads and limbs were hacked off, eyes put out, soldiers beaten to death. The French national epic poem, La Chanson de Roland, depicts men being split from skull to breastbone by the stroke of a sword, while at Hastings, the Danish axes wielded by the Saxon housecarls were said to cleave both rider and horse in twain at a single blow. Despite the massed formations of the Greek phalanxes and the Roman legions, at root the clash of armies was a clash of individuals, a prolonged series of simultaneous hand-to-hand combats, encounters from which only one man at a time could emerge victorious. The modern notion of a humanitarian, “proportional” war (surely an oxymoron) was utterly foreign to them. A soldier’s job, as Patton put it so bluntly and yet so eloquently in a speech to his Third Army during World War II, was to kill or die: “No bastard ever won a war by dying for his country. He won it by making the other poor dumb bastard die for his country.”

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

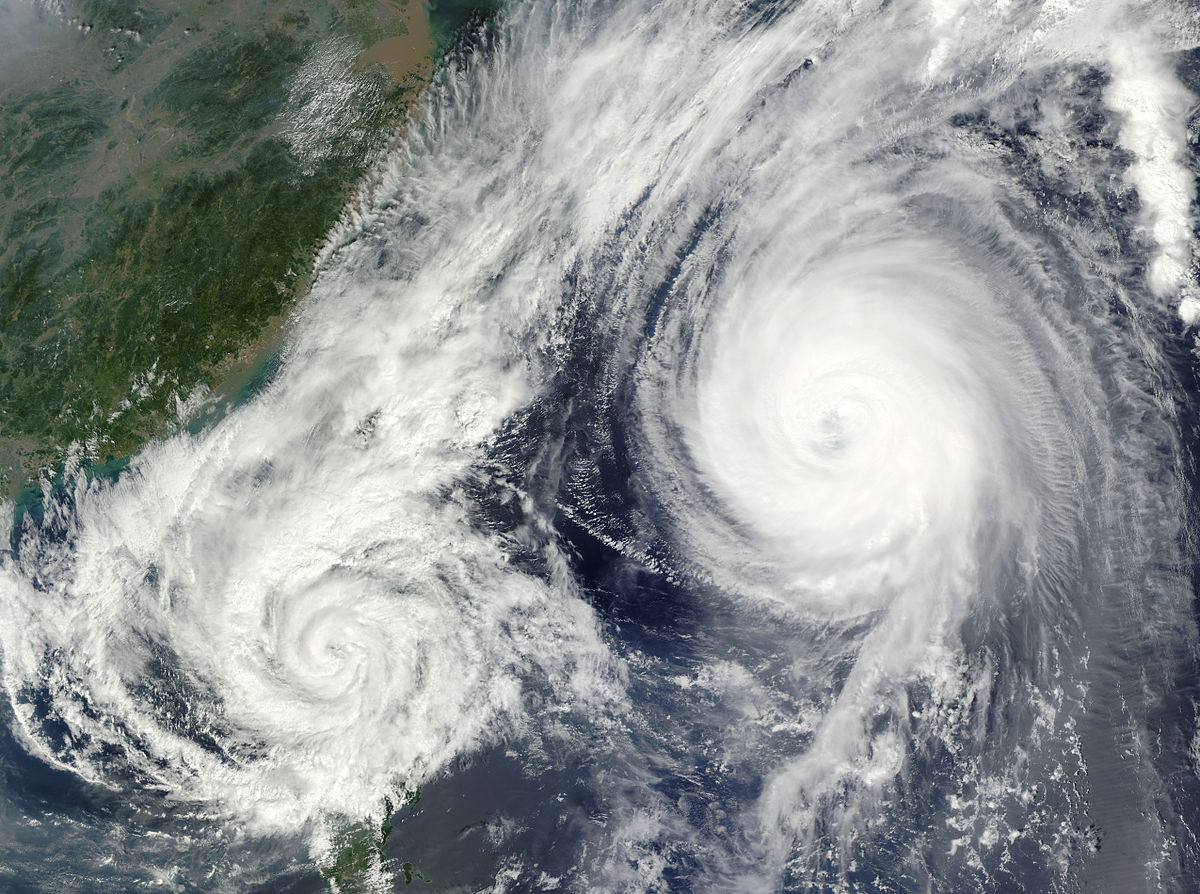

Two stormfronts are on a collision course over America. Where will it end?