"Porn literacy" aims to make sure that schools are exposing kids to the broadest range of sexualized matter.

“Great Books” Is for Losers

If you’re making a list, you’ve already lost.

“A great book is a great evil”

“μέγα βιβλίον, μέγα κακόν”

-Callimachus

American voters have given the incoming Trump administration a decisive mandate to reform the way we train our upcoming generations, from Kindergarten through PhDs. But scan through some conservative responses to America’s education crisis, and you will find a uniquely American solution repeatedly proposed: start a “Great Books” curriculum.

The theory goes that a quality “liberal arts” education—nay, even a classical education—consists mainly in reading, and thoroughly discussing,a series of important books dating from (perhaps) antiquity to the recent past. Not just any book will do: only the “great” ones. Shakespeare, Milton, Dostoyevsky…and so on. The canon.

But anyone putting faith in such a “Great Books” education—whether begun in high school, or college, or through independent self-study—in the hopes of restoring American culture, should pause and ask himself: what exactly is being restored?

The Birth of a Cope

Whenever “The Great Books” are criticized, or “expansions” of them proposed, readers with even a short cultural memory are likely to imagine scenes from the culture wars of the ’80s, ’90s and beyond, when radicals fulminated against “dead white men.” We think of the Stanford decanonizers exposed by David Sacks and Peter Thiel in The Diversity Myth (1995). Our hackles begin to rise.

But it’s time to face an uncomfortable fact. Upon examination, an education based on a “Canon” of “Great Books” turns out to have been designed by, and for, losers. Moreover, it is foreign to the spirit of the Renaissance, the American founding, and Classical Antiquity itself. The whole concept is in fact quite new. And for anyone on the Right, accepting the “Canon” premise is tantamount to admitting defeat.

Consider some of the country’s most revered “Great Books” programs. Saint John’s College in Annapolis implemented a well-known one in 1936—after losing its accreditation. The idea had only really been around since 1919, when Columbia University pioneered its famous Great-Books heavy “Western Civilization” sequence. Reed College soon followed suit in 1921. But perhaps the most famous and paradigmatic Great Books program was that founded at the University of Chicago in 1931 by the school’s president, Robert Maynard Hutchins, and Mortimer J. Adler—the latter himself a graduate of Columbia’s program.

The spirit animating Chicago’s program and perhaps all such programs may be discerned in Encyclopedia Britannica’s subsequent publication of the Great Books of the Western World. In the 1940s, a committee of 35 distinguished scholars gathered for an important (and duly compensated) mission. Adler, the committee’s chair, charged the luminaries with cataloguing 500 of the West’s greatest “ideas.” These were then distilled down to the 102 most important ones. From this more pure isolate was then derived a list of certain Great Books which were determined to have contributed most to the formation or trajectory of those ideas.

It was an incredible labor, no doubt one of earnest love. Some 400,000 man-hours, many of them billable, had to be entered into Britannica‘s ledger. But the first edition of The Great Books of the Western World emerged at last in 1952, and consisted of 75 authors arranged in 54 volumes, stretching from Greece to the early 20th century. Armed with the collection’s marvelous origin story, reflecting as it did the enlightened ideals of our scientific Academy, an army of door-to-door salesmen eventually made the collection a bestseller and a million-volume commercial success.

While Adler’s Great Books project certainly assembles a noble collection of books, most of them indeed worth reading at some point in life, to base a curriculum on it would have seemed odd and novel to (say) the U.S. Founders. To cite but one non-classical feature, the “read and discuss the Canon” approach assumes the priority of timeless “ideas.” Yet “ideas” are themselves a thing whose metaphysical status has been debatable at least since Aristotle, and to assign them priority in education over, for example, people, events, or discrete historical institutions seems itself to be an accident of some transient historical circumstance.

We should be gracious toward those humane Great Books innovators, for they developed this approach in order to bridge a yawning chasm opened up by a massive transformation of American education over the previous two generations. The outlines of this transformation (on which, more below) are detailed by Eric Adler in his 2016 monograph Classics, the Culture Wars, and Beyond.

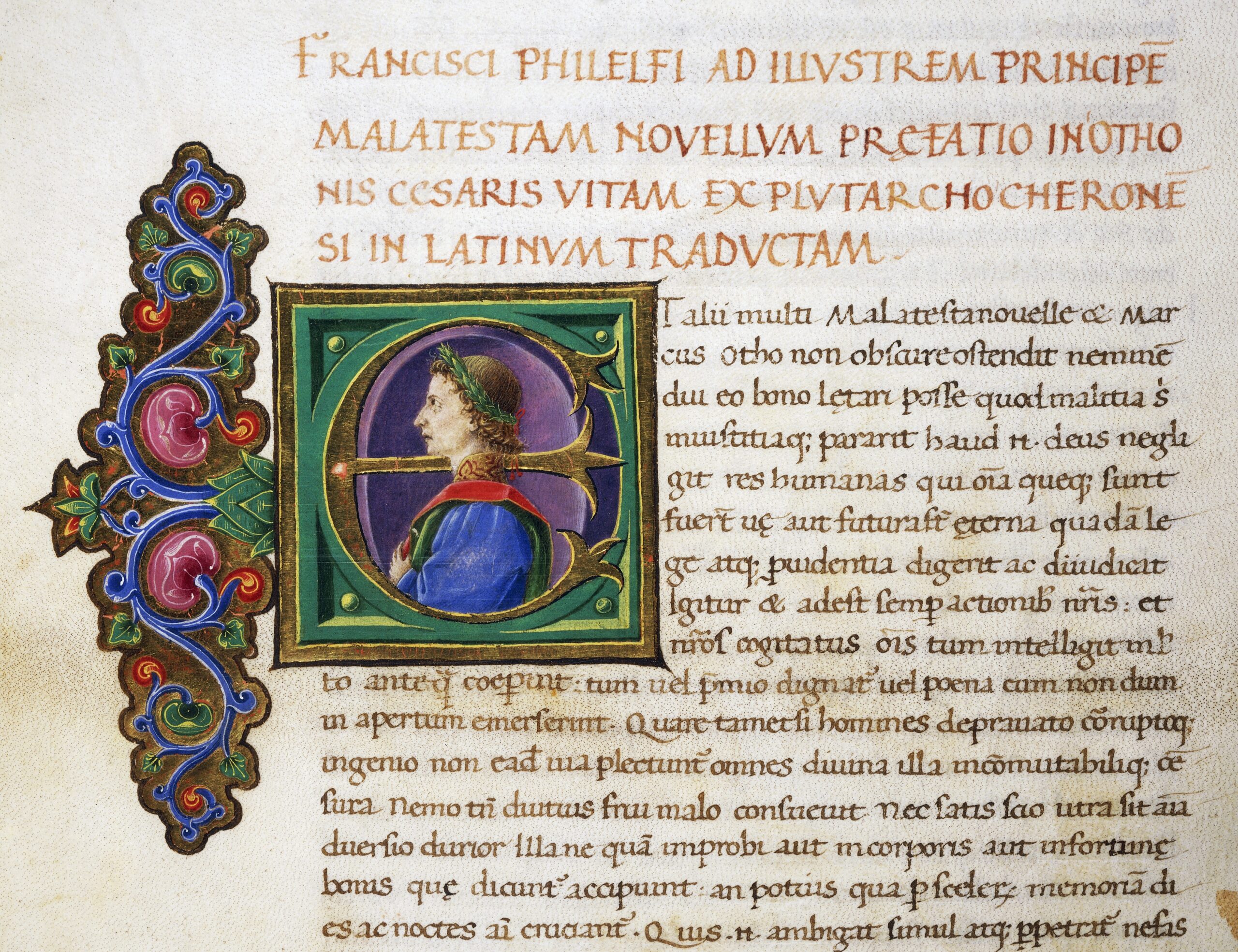

Before the transformation in question—in the 18th century, for example—American higher education in literature was dominated by what (Eric) Adler calls the Renaissance Humanism model, based almost entirely on careful study of the Greek and Roman classics. As he explains, “Renaissance humanists argued that classical Latin…was the key to the proper molding of individuals. Learning to write like the ancients would enable one to absorb their thoughts on moral philosophy.”

This educational paradigm eventually won purchase in those former bastions of medieval scholasticism, Oxford and Cambridge, whence it was subsequently transferred to the nascent American Colonies through early institutions like Harvard and Yale. This “Renaissance Humanism” model became the paradigm by which America’s colleges crafted figures like Cotton Mather, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson into public men. Figures like George Washington and later Frederick Douglas were self-educated, but their independent study was made easy because they were able to follow this obvious, established path.

The “humanist” model itself was not invented in the Renaissance, but based largely on the paradigms of education forged in the ancient Greek and Roman schools of oratory, attended by the likes of Demosthenes, Cicero, and Caesar. It was an education founded emphatically and rigorously on the bedrock of imitation—mimesis in Greek, carried roughly into Latin as aemulatio, or the “emulation” of role models. This was an education for statesmen. In the past, it went by another name, which has become in our day so debased as to be unrecognizable: rhetoric, the “speaker’s art.”

Not Great Books but Great Men

The classical paradigm comes from the world that, in order to characterize its ideal writer-orator, produced concepts like the “sublime,” which in Longinus’ Greek original literally means “magnitude” or “height” (“hypsos“). For no one can successfully lead free men without greatness.

The criterion for inclusion in this “canon” has little to do with “ideas,” and is more akin to the Homeric concept of aretē, understood as frightening manly excellence. Indeed, it is less a canon of “Great Books” and more a canon of “Great Men” worth imitating. That their words and deeds are recorded in books is virtually accidental to the concept. The whiff of this thought world is still detectable in both the prose and the actions of men like Hamilton and Napoleon. It was this paradigm that made not Virgil, not Catullus, not Plato or Aristotle, not even Caesar, but the mimesis-obsessed Parallel Lives of Plutarch the most popular ancient book (besides the Bible) in the American colonies.

Over the course of the 19th century, however, through a complex process, this paradigm was thrown out. To be sure, there are many factors at work here: the importation of German research methods which, among other innovations, reoriented the priorities of Classics around “Scientific Knowledge”; also contributing to the decline was the massive, populism-powered Morrill Land Grant program, starting in 1862, founding new schools which often heavily emphasized vocation and trades.

But technical competence is in no way opposed to Renaissance rhetorical humanism. Instead, the moral energy actively interested in ousting the Renaissance paradigm was the rise of liberal American Progressivism, with its “educational philosophers” like John Dewey and Charles Eliot of Harvard. (In Battle for the American Mind (2022), David Goodwin and Pete Hegseth tell a parallel story of how such reformers gutted what they call the “Western Christian Paideia”.)

Eric Adler’s book catalogs how, by the beginning of the 20th century, many American colleges had been reoriented around a confusing and priorityless buffet of subjects, including new “disciplines” like Sociology, Comparative Literature, Economics, etc.—the array of soft subjects ever expanding as specialization-hungry Ph.Ds searched for more niches in which to produce new “knowledge.” Among these subjects was the newfangled discipline of English Literature—Shakespeare, mind you, was not found on any college “canon” prior to the late 19th century. A great author, indeed, but not a classic in the original sense.

The confused eighteen year old, entering this new world, might reasonably think to himself, “Why should one pick this old book over that old book? Why is something 2,000 years old better than something 200, or 20 years old? For progressives like Charles Eliot, Harvard president from 1869 to 1909, this sense of bewilderment was a good thing. Look through our expansive course catalog, my boy, and choose whatever seems best. Eliot insisted that the playing field should be leveled: let a Darwinian Hunger Games among all legitimate subjects winnow out the “weaker” contenders; let Nature (and Science) decide whose lectures (and faculty budgets) shall be filled and whose drained.

To open up the “market” in this way, by placing all subjects on a supposedly equal footing, was a brilliant and devious method for sidelining tradition-heavy and authority-heavy disciplines, especially the Classics in the aforementioned sense. To the untrained eye, the process looked either completely accidental (“it’s not happening”) or represented an inevitable step in the progress of history (“and it’s good that it is”). Of course, the game was rigged: a discipline like Classics, imposing formidable hurdles like the mastery of Greek and Latin and an extensive body of mandatory content (similarly Theology and Biblical Studies—in their erstwhile, more rigorous, and now extinct forms) were doomed to lose to “relevant” and easy fields like “Psychology.”

Make Language Dangerous Again

This was of course the goal from the beginning: patriarchal moral roadblocks had to be bulldozed in order to make straight the way for social progress. That lofty task, of course, was left for the Frankfurt School and the Cultural Marxists to complete after the Second World War, and we enjoy the fruits today. But much of the city block flattening of America’s cultural edifices was already complete by the time a 1912 survey found that out of 155 top American public and private colleges and universities, only 27 (=17%) demanded Greek and Latin for a BA degree. This seems, proportionally, like a lot to us today, but the scale of defeat this figure represented would have stunned (say) the defenders of the Classics who produced the Yale Report of 1828. Eliot’s Harvard, for its part, had already dropped its Greek admissions requirement in 1886.

The Classics had already lost by the time the “Great Books” paradigm was born into a crumbling world. To be sure, we should be grateful to Hutchins, Mortimer Adler, and others for their efforts. Something had to be done, after all, to stanch the bleeding. But if ever for a moment they thought of themselves as defending the classics, then they were already losers.

To recover the dynamic and dangerous spirit that forged America and other great states, we must take stock of the true classical tradition that we’ve lost. The Great Books model, for example, has little interest in mimesis—except perhaps as one more neat “idea” among a long list of others to ponder and “debate.” In fact, the Great Books perspective makes few real claims on its students at all, other than a vague devotion to thinking hard, about a whole bunch of good stuff, some of it old. Its harmlessness, one suspects, has been key to the idea’s survival in polite circles to this day.

The most telling sign of Great Books education’s toothlessness is its abandonment of any serious engagement with the classical languages. Hutchins himself wrote in 1936, “I do not suggest that learning the languages or the grammar in which the ancient classics were written is necessary to general education. Excellent translations of almost all of them now exist.” Mortimer Adler himself never learned any foreign language, classical or otherwise.

Modern proponents of Latin and Greek often wring their hands coming up with reasons why people should learn the ancient languages—mental training, learning grammar, all the etymology, “ah the sound of the poetry,” etc. But they routinely omit the most important and even obvious one: language facilitates mimesis. Indeed, it is the most powerful vector of mimesis, for language structures consciousness. A Renaissance man like Machiavelli wished to conform his entire person—his mind most of all—to the greatness he found trapped in the pages of ancient books. Though he may hide his secret in order to flatter his Greekless patrons, the classical zealot knows that assimilating the actual thought patterns of the greats—by reading them in the original language—is the most powerful spell he can use in his quest.

Faced with such magic, the “Great Books” dilettante can only stare in uncomprehending awe.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The fight for Catholic schools and the future of American institutions.

A free society depends on a free and open exchange of ideas.

Arguments against school choice miss the mark.

Wokeness is threatening our nation's historic sites.

Freedom of choice can break the educational testing monopoly.