The dark history of the radical Left's enforcement arm.

Columbus’s Voyage of Discovery

The true story is far more interesting than leftist myths.

If the name of Christopher Columbus has caught your attention in the past few years, it almost certainly has been accompanied by lurid accusations and demands that Columbus Day be renamed Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

In a modest attempt to correct the record, I will use primary sources written in the 1500s. In Spanish. The following history comes from Los Cuatro Viajes del Almirante y su Testamento and Brevísima Relación de la Destrucción de las Indias, both written by Bartolomé de las Casas, as well as a biography of Columbus; The Book of Privileges, in which Columbus details the legal aspects of his voyages; and narration of his exploration by Columbus’s son, Fernando.

Las Casas became a fervent advocate for the natives on the recently discovered continent after witnessing the atrocities Spaniards were carrying out, which would ultimately result in their dying out. He was a detailed chronicler and named names. Las Casas met many who had known Columbus (including his own father), and he records that Columbus often stood in the way of the Spaniards’ depredations. This is why I prefer to rely on Las Casas’s testimony from the early 1500s instead of 20th century Marxist pseudo-historians and cartoonish YouTube videos.

To blame Columbus for what the Spaniards did years after he died is like blaming the Wright brothers for the bombing of Rotterdam, Dresden, and London during World War II.

Here’s what really happened.

The Spanish monarchs gave Columbus permission to set off on a voyage to Asia after initially rejecting his proposal (royal advisors maintained that Columbus had underestimated the distance to Asia). No one, of course, thought there was an undiscovered continent in the way or that the Asian continent would be larger than imagined. The mission was to secure a trading agreement with Asia and claim vacant lands encountered on the way for Spain, either as a trading station or a resupply point, thereby imitating Portuguese strategy in Africa.

Queen Isabella was ready to pawn her jewels to finance the voyage, but it proved unnecessary (contrary to popular belief, the monarchy was not wealthy, hence its desperation for gold and silver). Not only was the monarchy far from wealthy, but it also lacked enforceable authority. The queen ordered the residents of Palos de la Frontera to furnish Columbus with caravels as payment for a fine they had incurred; they ignored the order. No sailor was interested in going on such a harebrained voyage led by a stranger, and a foreigner to boot.

Martín Alonso Pinzón, a local wealthy merchant and navigator, agreed to partly finance the trip and supply men and ships. Ninety men set off on September 6, 1492. Toward the end of the voyage, the men on Columbus’s caravel were thinking of mutiny; it took Pinzón’s authority to quell the rumblings through his personal reputation and his threat of hangings. On October 11, a sailor reported dim lights on the dark night, and on the 12th, Columbus sighted land (a little known fact is that millions of species of luminous worms came to mass-mate on the surface of the water in that area in 1492).

When the natives saw boats arriving, they fled (which would be a recurring pattern). This was because the Taínos, Arawaks, and Siboneys were food for seafaring cannibals. But the Caribs had a technological advantage over the noncannibals: bows and arrows, whereas the Siboneys, Arawaks, and Taínos had sticks. The latter were also stark naked, and some were as white as any European.

The cannibals would capture them, tie them up, and take them back to their islands, where the women would be repeatedly raped over a matter of weeks before being eaten—this after their men and male children had been castrated (to make their meat tender), dismembered, and eaten. Later on, when Columbus encountered a deserted cannibal village, he found arms, legs, and a disemboweled torso grilling on the fire; a terrified captured women begged the Spaniards to be taken away. It was these cannibals that a disgusted Columbus initially thought should be enslaved.

The Spaniards were able to capture some of the native women for a few days, during which time Columbus quickly learned their language (he was a polyglot). The women were treated well, given gifts, and then released, whereupon the rest of the natives returned to befriend them.

From the Bahamas, Columbus and his crew then discovered Cuba (which he named Juana) and journeyed for some time along the northern coast hoping to find Cathay. Though entranced by the beauty of the land, complete with lush vegetation and knowing no autumn, there were no cities. In a letter to the voyage’s treasurer written at the end of the journey, Columbus states it was a very fertile part of Asia. Around this time, Pinzón grew upset at the failure to find civilization and went AWOL.

Throughout his voyages, Columbus collected details about the people he encountered, including their customs, and traded for their utensils and parrots to provide evidence of his success. It is for this reason that American historian Edward Bourne considered Columbus the first ethnographer of the New World.

Sailing eastward, Columbus found Hispaniola and made contact with the natives there. To the voyagers’ delight, they were told that gold nuggets were strewn on the ground in many places, and Columbus traded for the nuggets that the natives used for decoration.

One of the caravels was destroyed on a coral reef in Hispaniola around the time Pinzón returned, having also found nuggets (Columbus also released the natives Pinzón had kidnapped). This accident necessitated leaving some men on the island—and proves that, contrary to modern lies being propagated, he did not bring back thousands of Indian slaves on his first voyage (I have been in a caravel; it is equivalent to a small tugboat).

An outpost was built for the men and a cannon left behind. On firing the cannon, Columbus explained to his friend, the local cacique (chief), that the cannon would prevent cannibals from landing. The men were given strict orders to be on good terms with the natives. The crew even took a few natives who went willingly with them. (If a UFO landed and you were offered a trip to another planet and you’re a young man, wouldn’t you go?)

On the way back, the ships ran into a storm and separated. Pinzón landed in Spain and sent a letter to the monarchs announcing their success. He then returned to Palos de la Frontera where he died from illness, possibly yellow fever.

Columbus landed in Lisbon, where he was arrested and later released, and proceeded to Spain, where the monarchs gushed over him, realizing the significance of his voyage and ogling the nine natives and objects he brought back (the natives returned home on the second voyage). After Columbus’s first expedition, opinion greatly differed, with some believing he had reached Asia while others concluded he had discovered a new continent.

News of the discovery traveled fast. Indeed, in 1496 Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot), a fellow Genoese, sailed from England to the New World but was forced to return. Cabot set sail again the following year with just one ship and reached Canada. A second expedition followed a year later. A third one in 1498, this time with five ships, saw Cabot’s death. Details of his voyages are scant, unlike those of Columbus. In 1499, an Englishman, William Weston undertook another expedition to North America.

It has become de rigueur to dismiss Columbus’s achievement by saying others before him discovered the Americas. Endocrinologist Hans Selye, though, pointed out the obvious significance of his journey in From Dream to Discovery: “The important difference between the discovery of America by the Indians, by the Norsemen, and by Columbus is only that Columbus succeeded in attaching the American continent to the rest of the world.”

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Trump is right: only patriotic American history can heal our deep wounds.

What's today really about?

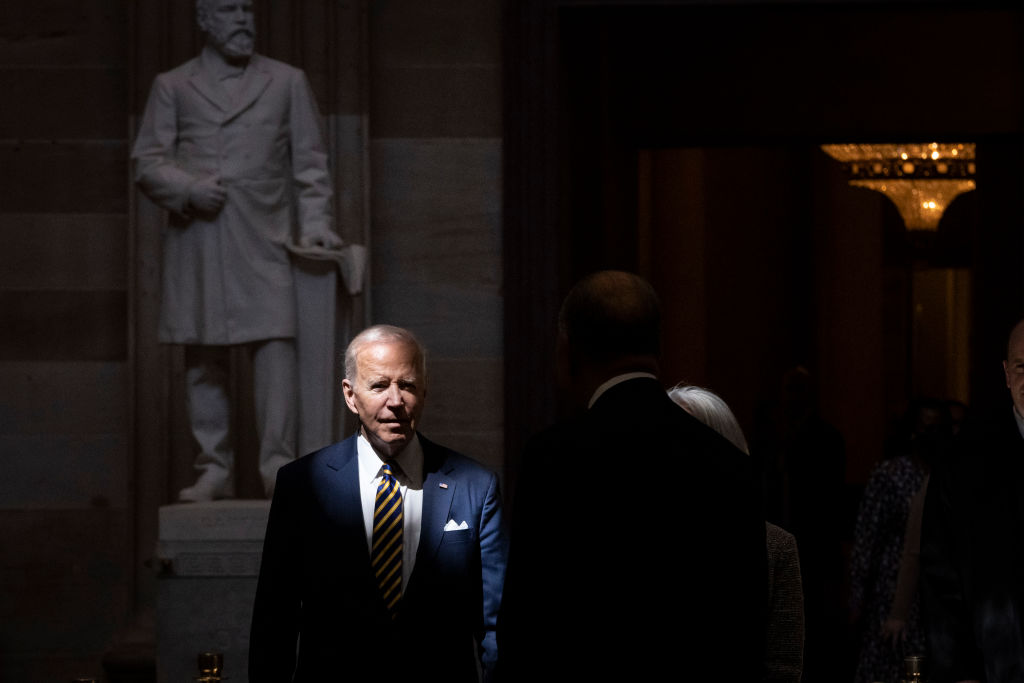

Joe Biden and the dangers of posterity.

Biden's historians fantasized about FDR, but the reality will be closer to Carter.

Is Stoicism strong enough to make things cohere?