A clarifying exchange.

Recovering the Commerce Clause

Could the end of the Wickard precedent be near?

One of the worst decisions in Supreme Court history might finally be overturned.

Filed in January 2024, John Ream v. U.S. Department of the Treasury could cast aside Wickard v. Filburn (1942) could put an end to the Court’s rampant abuse of the Constitution’s Commerce Clause to justify whatever Congress wants to do.

The plaintiff is asking for declaratory and injunctive relief to overturn the current federal ban on distilling alcoholic beverages at home for personal and family consumption. Mr. Ream wants to produce rye and bourbon and has no plans to sell or offer it to the public. He believes that this prohibition exceeds the powers of Congress under both Article I and the 10th Amendment.

Although current statutes expressly authorize the home production of both beer and wine, 26 U.S.C.§ 5601(a)(6) prohibits home distilling of whiskey. Interestingly enough, 26 U.S.C. § 5181 allows for personal production of ethanol to produce fuel for farm use—and the same distilling process can also be used to produce whiskey.

The complaint in John Ream correctly notes, “If Congress can prohibit home distilling, it can prohibit home bread baking, sewing, vegetable gardening, and practically anything else.” How did Congress get the authority to regulate virtually anything under the auspices of commerce?

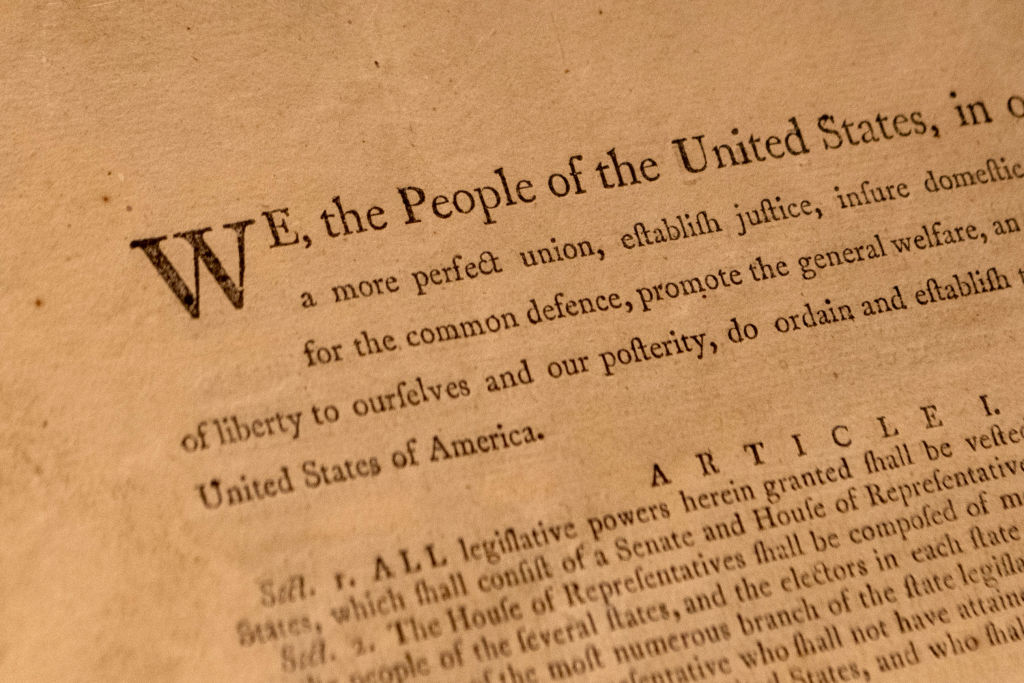

One of the enumerated powers the Constitution grants to the legislature in Article 1 is to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes.” However, the Constitution nowhere defines the parameters of what qualifies as “commerce.”

Early in American history, the exact limits of the Commerce Clause were not a critical issue. Most commerce during that period was intrastate, as both agricultural and manufactured products were sold close to where they had been produced. Large scale shipments of goods over long distances did not became widespread until the transcontinental railroad was completed in the latter half of the 19th century.

In order to regulate railroad rates, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was created in 1887. The ICC was the first independent regulatory agency, marking the beginning of what has come to be known as the administrative state. The agency’s authority eventually expanded to cover other aspects of the railroad industry, and also the telegraph, telephone, and radio (until the creation of the Federal Communications Commission in 1934). In 1935, the Motor Carrier Act was enacted, establishing the ICC’s authority to regulate the trucking industry as well. Of course, regulating the operation of interstate common carriers is clearly compatible with the Commerce Clause.

But the Supreme Court’s decision in Wickard declared that almost anything can be defined as interstate commerce, breaking with all previous precedent and history. The facts of the case were so incongruous with the result that it was almost as if the Court was looking for a pretext to say that the Commerce Clause means whatever FDR’s government wanted it to say.

The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 had given the government the authority to determine the amount of wheat that farmers were allowed to grow, which was done to control market prices by limiting the supply of wheat. Ohio farmer Roscoe Filburn raised dairy cattle, poultry, and also wheat, most of which was used to feed his own livestock. He was notified that he would be authorized to plant 11.1 acres of wheat to be harvested in 1941.

However, he planted and harvested 23 acres, which resulted in a yield of 239 bushels, which was in excess of what the government had decreed he should be allowed to produce. Government regulators determined that this constituted “farm marketing excess subject to a penalty of 49 cents a bushel or $117.11 in all.” Filburn contested this action on the basis that the wheat he grew and fed to his own livestock never left his farm—and certainly never crossed a state line. However, the government argued that his action was illegal because it had an effect on interstate commerce. Roscoe Filburn’s choice not to engage in interstate commerce therefore supposedly influenced crop prices nationwide.

A unanimous Supreme Court declared that Congress could define something as interstate commerce simply by choosing to do so. Their decision in Wickard v. Filburn opened the door for Congress to enact legislation on the basis that almost anything could affect interstate commerce. This frequently includes regulating activities that are entirely local in nature and have nothing to do with any form of commerce.

The rationale for the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990, for instance, was that since the operation of schools has an effect on interstate commerce, the Commerce Clause therefore provided the basis for federal legislation prohibiting carrying firearms within 1,000 feet of a school. This was a clear example of Congress acting to legislate on a question that should have been a matter addressed by each individual state.

Deals New and Old

Though the Court in U.S. v. Lopez (1995) overturned the Gun-Free School Zones Act on the grounds that it was not related to interstate commerce, just ten years later in Gonzales v. Raich (2005), they reverted back to the precedent they had set in Wickard. That opinion held that California’s decision to legalize the cultivation of medicinal marijuana for purely local consumption as prescribed by a licensed physician violated the Controlled Substances Act. The majority reasoned that California would “undercut the regulation of interstate commerce in that commodity [marijuana].” However, the intent of that portion of the Controlled Substances Act was not to regulate the interstate commerce of marijuana but rather to prohibit both interstate and intrastate commerce in marijuana.

The John Ream case appears to be a perfect opportunity for the Court to overturn decades of bad precedent and limit the Commerce Clause to regulating activities which are actually interstate commerce.

It is quite obvious that the government will strongly oppose a ruling that could place significant limitations on their use of the Commerce Clause as a means to expand their power to regulate and tax all sorts of activity. Just as the Commerce Clause was used to enact some of the most onerous features of the New Deal, there is no doubt that D.C. is full of officious bureaucrats who would like to use it to enact their vision of a Green New Deal.

While it would certainly be a good thing if the Supreme Court corrected this problem in John Ream, there is no need to wait for that to happen.

Legislation is always preferable to litigation. The time is long overdue for Congress to reassert its constitutional authority and define the proper limits of the Commerce Clause.

Here are a few things that should be defined by such legislation:

Selling goods that are entirely produced in one state and transported to another state for sale to the consumer is clearly interstate commerce. For example, when an agricultural product is entirely produced in one state and used or sold within that same state, that is intrastate activity and should only be regulated and taxed by that state.

However, when a product is produced and sold within a single state using materials that are purchased from a vendor within the same state, the vendor should not be considered to be engaging in interstate commerce. The retail seller who has never had any contact with a producer in another state is simply engaging in a local activity. Likewise, the idea that someone from another state can come into a store and buy something would not make the slightest difference to any retail merchant.

If the wholesale vendor or producer of materials has obtained such goods from another state, that person is engaging in interstate commerce and can be regulated and taxed accordingly. However, there is no justification for alleging that any remote connection to a distant transaction in another state means that any merchant or customer who might come into contact with such goods has therefore engaged in interstate commerce.

Our current practice is clearly not something that the Founding Fathers would have ever intended when they wrote the Constitution. It is time to utilize the legislative process to resolve this problem.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Undoing a corrupt eminent domain case doesn’t justify society-wide wealth redistribution.

Trump’s call to end birthright citizenship is a necessary corrective.

Too often, experts who are working to "save American democracy" are doing anything but.

Critical race theory was never designed to reveal truth—it was designed to achieve power.

Jack Smith’s indictments of Donald Trump are unconstitutional because he was already tried in the Senate.