Conservatives need to stop treating virtue signaling as if it didn’t matter.

Why is Everything Liberal?

Cardinal Preferences Explain Why All Institutions are Woke.

This essay was originally posted in Richard Hanania’s Newsletter. For the followup to this post, see “2016: The Turning Point.”

In a democracy, every vote is supposed to be equal. If about half the country supports one side and half the country supports another, you may expect major institutions to either be equally divided, or to try to stay politically neutral.

This is not what we find. If it takes a position on the hot button social issues around which our politics revolve, almost every major institution in America that is not explicitly conservative leans left. In a country where Republicans get around half the votes or something close to that in every election, why should this be the case?

This post started as an investigation into Woke Capital, one of the most important developments in the last decade or so of American politics. Although big business pressuring politicians is not new (the NFL moved the Super Bowl from Arizona over MLK day), the scope of the issues on which corporations feel the need to weigh in is certainly expanding, now including LGBT issues, abortion laws, voting rights, kneeling during the national anthem, and gun control.

Conservatives have taken notice. J.D. Vance appears ready to run for Senate, and it seems like opposing corporate power is going to be a major part of his political identity. Josh Hawley regularly introduces bills to harm this or that industry, often based on some position it has taken that he doesn’t like. We shouldn’t exaggerate the realignment too much; last time Republicans had control of government, their major legislative achievement was a corporate tax cut. Nonetheless, regardless of whether politicians are serious about doing something about Woke Capital, the phenomenon is interesting in and of itself for what it tells us about the nature of institutions in American society, and where our culture and politics are going.

As I started to research the topic, however, I realized there wasn’t much to explain. Asking why corporations are woke is like asking why Hispanics tend to have two arms, or why the Houston Rockets have increased their number of 3-point shots taken over the last few decades. All humans tend to have two arms, and all NBA teams shoot more 3-pointers than in the past, so focusing on one subset of the population that has the same characteristics as all others in the group misses the point.

I think one reason Woke Capital is getting so much attention is because we expect business to be more right-leaning, and corporations throwing in with the party of more taxes and regulation strikes us as odd. We are used to schools, non-profits, mainline religions, etc. taking liberal positions and feel like business should be different. But business is just being assimilated into a larger trend.

Corporations are woke, meaning left-wing on social issues relative to the general population, because institutions are woke. So the question becomes, why are institutions woke?

Ordinal Versus Cardinal Utility

While all votes count equally on Election Day, at all other times some citizens matter a lot more than others. For example, let’s say I vote Republican every two years, but otherwise go on with my life and rarely ever think about politics. You, on the other hand, not only vote Democrat, but give money to campaigns, write your Congressman when major legislation comes up, wear pink hats, and march in the streets or write emails to institutions when you’re outraged about something.

Through the lens of ordinal utility, in which people simply rank what they want to happen, we are about equal. I prefer Republicans to Democrats, while you have the opposite preference. But when we think in terms of cardinal utility—in layman’s terms, how bad people want something to happen—it’s no contest. You are going to be much more influential than me. Most people are relatively indifferent to politics and see it as a small part of their lives, yet a small percentage of the population takes it very seriously and makes it part of its identity. Those people will tend to punch above their weight in influence, and institutions will be more responsive to them.

Elections are a measure of ordinal preferences. As long as you care enough to vote, it doesn’t matter how much you care about the election outcome, as everyone’s voice is the same. But for everything else—who speaks up in a board meeting about whether a corporation should take a political position, who protests against a company taking a position one side or the other finds offensive, etc.—cardinal utility maters a lot. Only a small minority of the public ever bothers to try to influence a corporation, school, or non-profit to reflect certain values, whether from the inside or out.

In an evenly divided country, if one side simply cares more, it’s going to exert a disproportionate influence on all institutions, and be more likely to see its preferences enacted in the time between elections when most people aren’t paying much attention.

Accounting for Cardinal Utility

In simple terms, the theory presented here says liberals win because they care about politics more. Is there any way we can verify this is indeed the case?

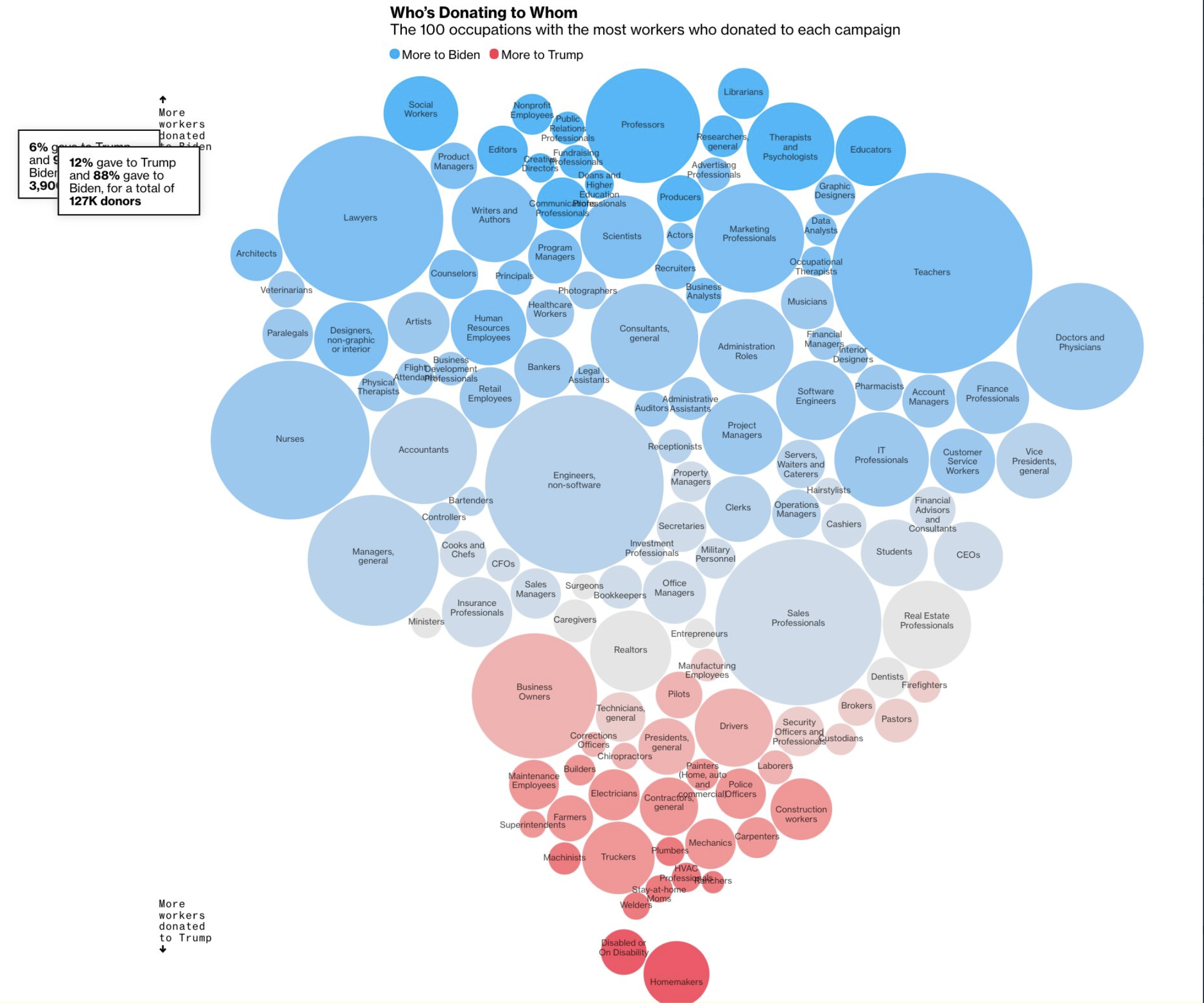

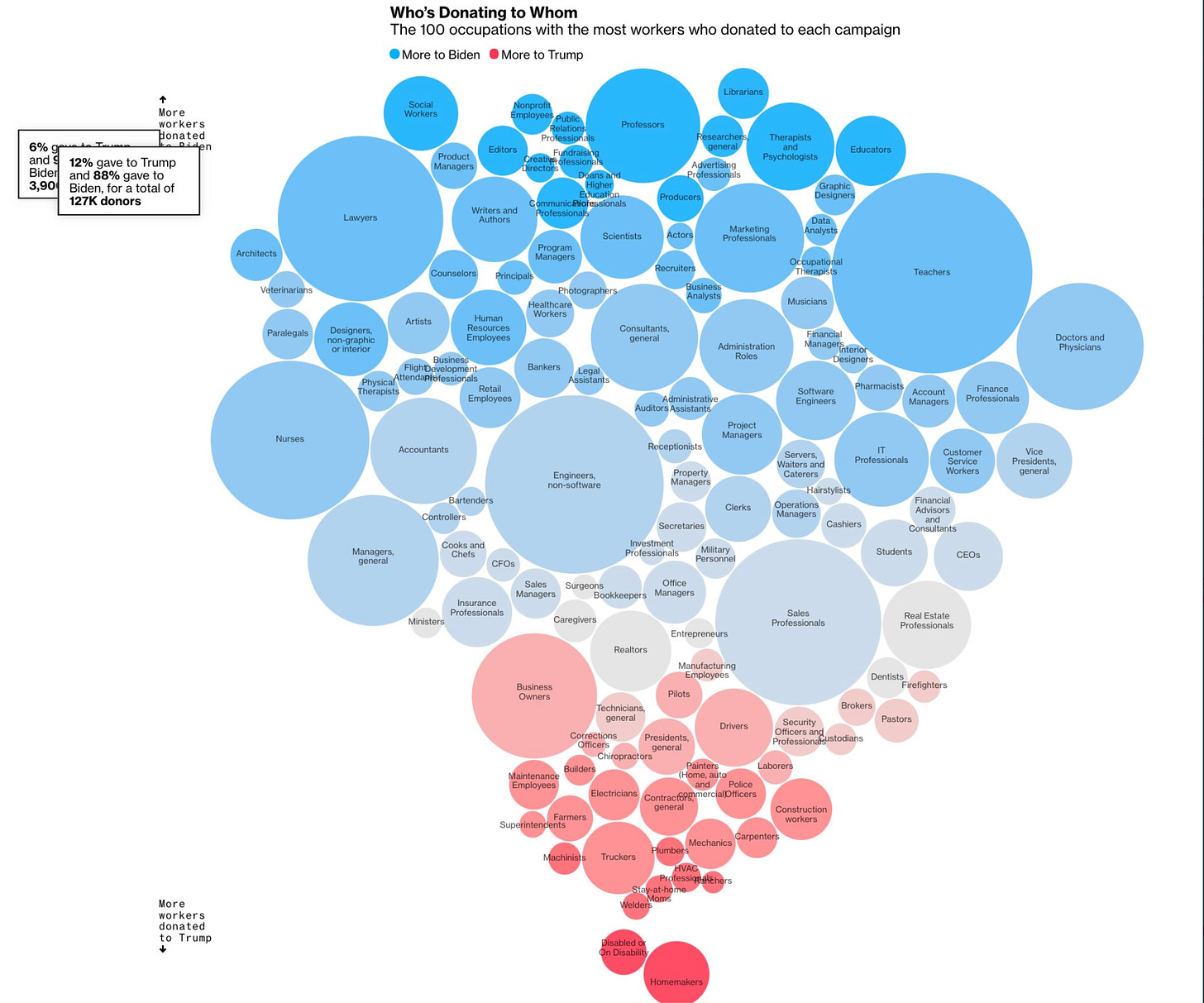

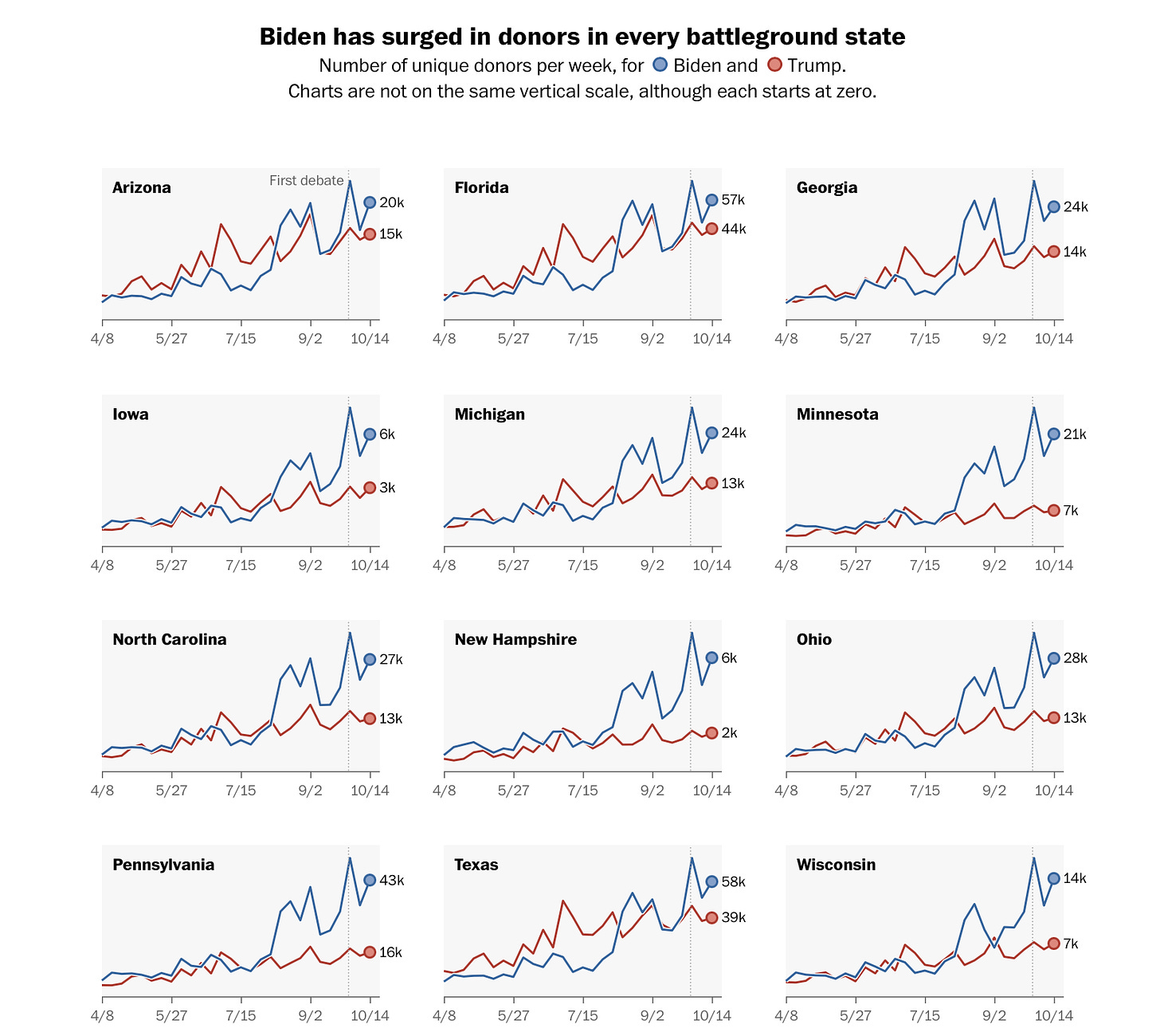

Here are two graphs that have been getting a lot of attention:

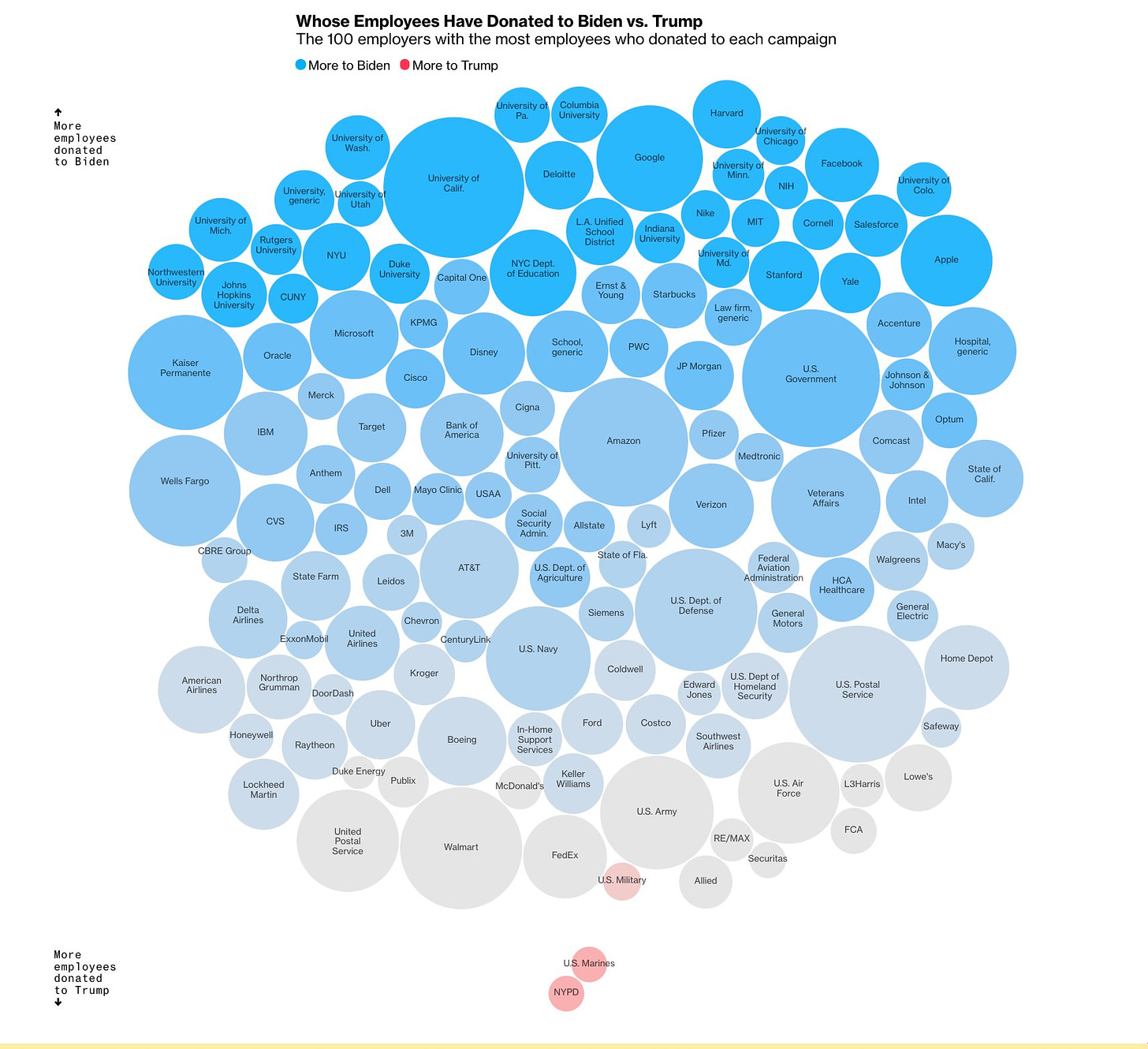

What jumps out to me in these figures is not only how left-leaning large institutions are, but how the same is true for most professions. Whether you are looking by institution or by individuals, there are more donations to Biden than Trump. Yet Republicans get close to half the votes! Where are the Trump supporters? What these graphs reveal is a larger story, in which more people give to liberal causes and candidates than to conservative ones, even if Americans are about equally divided in which party they support (and no, this isn’t the result of liberals being wealthier; the connections between income and ideology or party are pretty weak). Here are some graphs from late October showing Biden having more individual donors than Trump in every battleground state.

According to the Washington Post: “The Democratic nominee and his associated committees have received donations from nearly 5.9 million people, while Trump has seen donations from 3.7 million donors, according to The Washington Post’s analysis of data from the Federal Election Commission between Jan. 1, 2020, and Oct. 14, 2020.”

Assuming practically nobody donated to both Trump and Biden, which seems a pretty safe bet, as of late October, 9.6 million Americans donated to a presidential campaign, compared to 161 million who voted. In other words, 49.1% of all Americans cast a ballot in 2020, compared to 2.9% who cared enough to actually give money to one side or the other. This doesn’t include money donated to Super PACs, etc., nor does it take into account people who may have donated in the final weeks of the campaign or to a third party, but even if you did account for these things it wouldn’t change the larger story.

So while Biden beat Trump in the popular vote by 51%-47% (+4), in the donor game, Biden beat Trump by 61-39% (+22%). It is therefore unsurprising that Biden got more donors than Trump across most professions, and in almost every large institution.

This pattern doesn’t appear to be unique to 2020. In 2016, Hillary Clinton outraised Trump 2-1, including both the campaigns and Super PACs, although Trump did beat Hillary in number of small donors as defined by those making contributions of $200 or less.

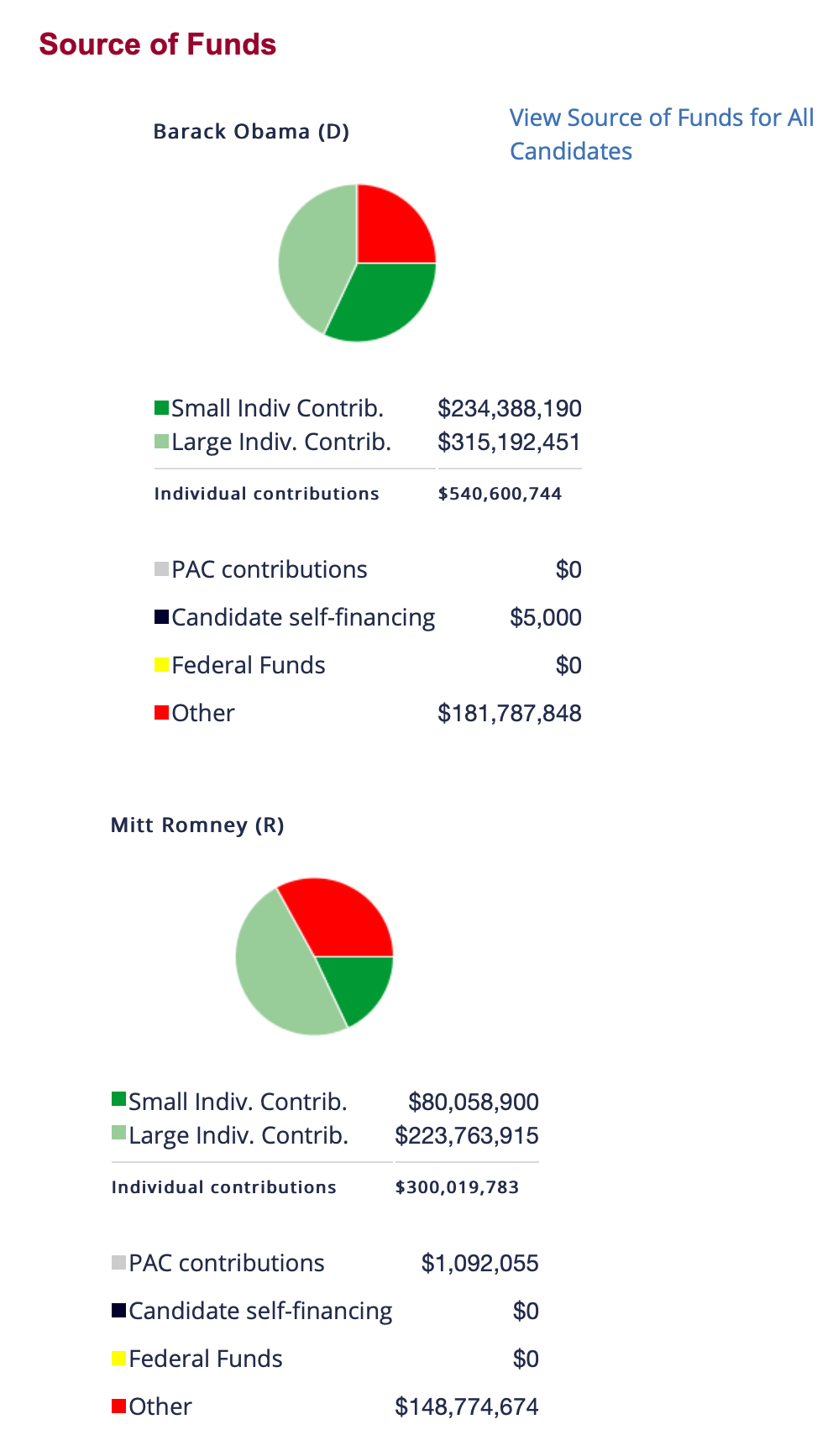

In the 2012 election, Obama raised $234 million from small individual contributors, compared to $80 million for Romney, while also winning among large contributors.

To put Biden’s donor advantage in context, in the 2020 election Biden beat Trump in the solidly blue state of Illinois by 17%. Biden’s 22% advantage over Trump among donors across the entire country is greater than his advantage among all voters in Illinois. In California, Biden won by about 29%, meaning as a class donors are closer to reflecting that famously liberal state than they are to being representative of the country as a whole (none of this is meant as a commentary on whether fundraising actually matters in presidential election outcomes, I’m simply using donors to each side and how much they donate as a way to get at the issue of cardinal utility).

In addition to money, another way to measure cardinal utility is to look at protests. I tend not to trust media or academic estimates for exact numbers, since these things are hard to measure and their political biases mean that they may exaggerate the number who show up for liberal causes and do the opposite for conservatives. Nonetheless, even with that caveat, I don’t think anyone would deny that the women’s march, BLM, and Occupy Wall Street have drawn many more people than rallies for the Tea Party and Trump.

In September 2009, at the height of the Tea Party movement, conservatives held the “Taxpayer March on Washington,” which drew something like 60,000-70,000 people, leading one newspaper to call it “the largest conservative protest ever to storm the Capitol.” Since that time, the annual anti-abortion March for Life rally in Washington has drawn massive crowds, with estimates for some years ranging widely from low six figures to mid-to-high six figures. March for Life is not to be confused with “March for Our Lives,” a pro-gun control rally that activists claim saw 800,000 people turn out in 2018. All these events were dwarfed by the Women’s March in opposition to Trump, which drew by one estimate “between 3,267,134 and 5,246,670 people in the United States (our best guess is 4,157,894). That translates into 1 percent to 1.6 percent of the U.S. population of 318,900,000 people (our best guess is 1.3 percent).” Even if the two left-wing academics who did this research are letting their bias infuse their work, there is no question that protesting is generally a left-wing activity, as conservatives themselves realize.

People who engage in protesting care more about politics than people who donate money, and people who donate money care more than people who simply vote. Imagine a pyramid with voters at the bottom and full-time activists on top, and as you move up the pyramid it gets much narrower and more left-wing. Multiple strands of evidence indicate this would basically be an accurate representation of society.

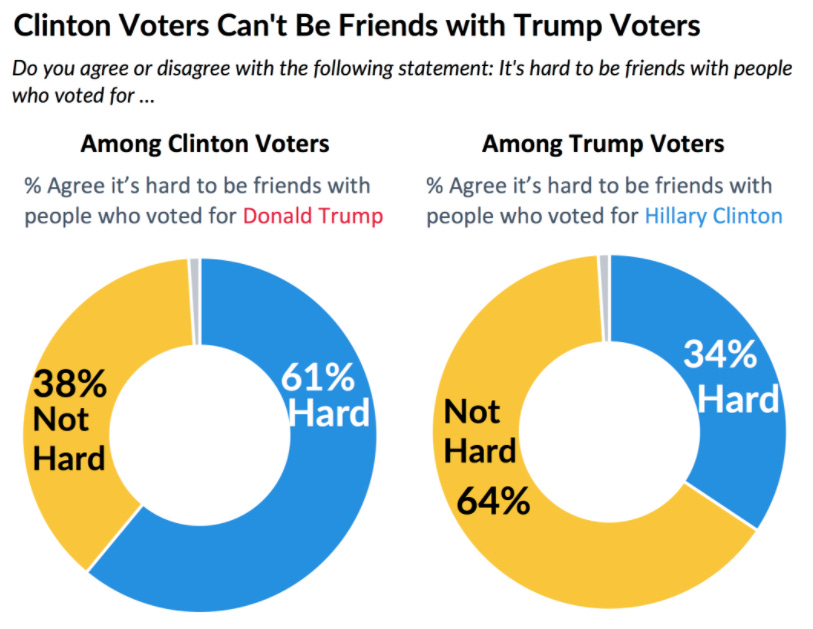

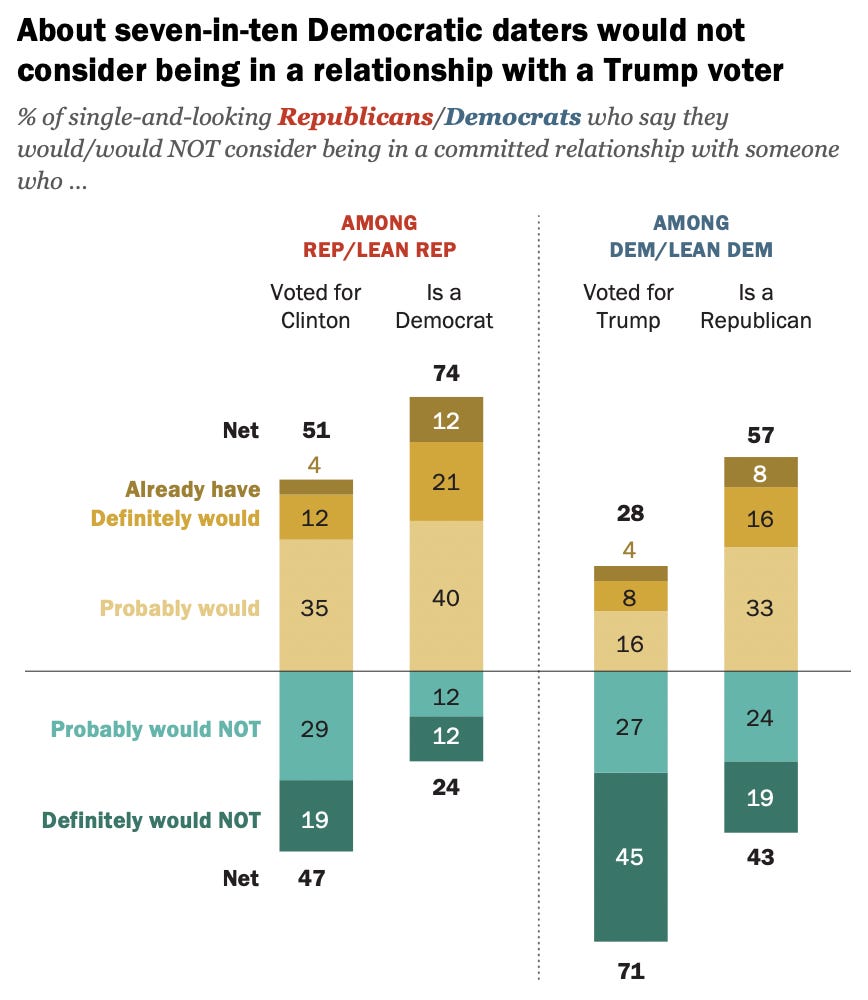

Another line of evidence showing that the Left simply cares more about politics comes from Noah Carl, who has put together data showing liberals are in their personal lives more intolerant of conservatives than vice versa across numerous dimensions in the U.S. and the U.K. Those on the Left are more likely to block someone on social media over their views, be upset if their child marries someone from the other side, and find it hard to be friends with or date someone they disagree with politically. Here are two graphs demonstrating the general point.

Not letting politics interfere with personal relationships is a sign that politics isn’t all that important to you.

A final way to understand cardinal utility is to consider the media and academia. Generally, these are professions that have absolutely terrible career prospects, and they draw people with high IQs who could expect to be making a lot more money doing something else. But for those who make it in these fields, individuals get to have an influence in society that is disproportionate to their status as measured by income. Of course, the media makes it harder to be a right-wing activist through doxxing, etc., and so that might explain to some extent why the Right is less politically active, though I doubt this is a large part of the story given how relatively little appetite there apparently is among conservatives even for right-wing activism in favor of positions and views that don’t tend to get one cancelled (i.e., donating to Mitt Romney in 2012).

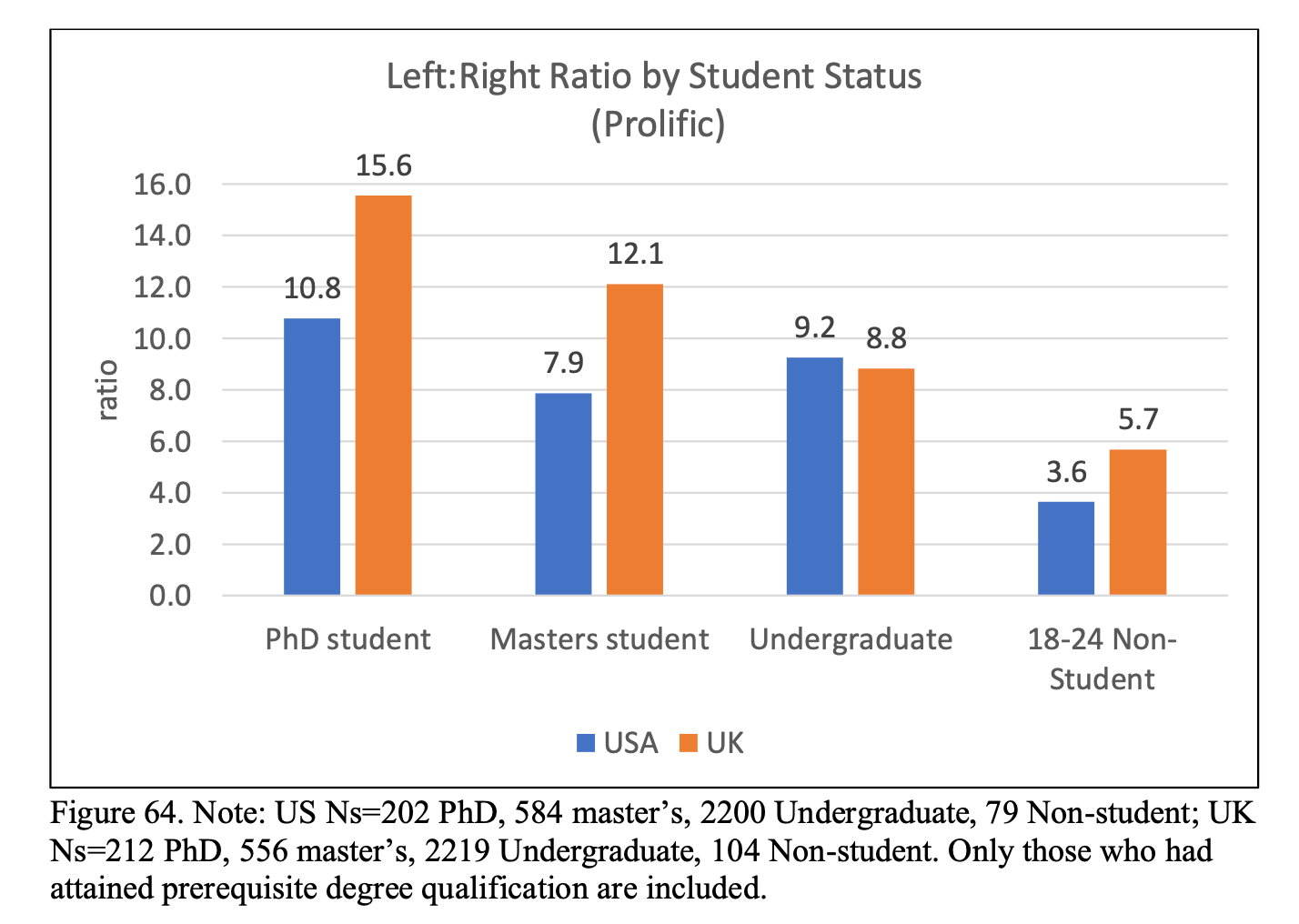

Eric Kaufmann wrote a report for CSPI highlighting anti-conservative discrimination in academia. While he is surely right that this exists, his data make clear that even absent discrimination liberals would still dominate the profession. He finds that in the U.S. and the U.K., there’s a ratio of about 10:1 to 15:1 for left-wing to right-wing PhD students, and smaller but still substantial gaps among Master’s students.

It is important to highlight just what an irrational decision going into academia is for a person who wants to maximize their lifetime earnings. Graduate school takes something like 6 years, during which you’re making something like a minimum wage salary as a college graduate. This is all in the hopes of getting a postdoc, perhaps bouncing around low-paying jobs for a few years, until the point where you finally find permanent employment at around 30 at the earliest. Even then you often don’t make as much money as a Walmart manager. And those are the successful cases!

People go into academia and journalism for generally idealistic reasons. Some conservatives might be turned away from these professions for political reasons, which poses a “chicken or egg” problem. In my experience though, a smart young person going into journalism is probably better off going into conservative media than they are liberal media, which is already saturated with people with elite degrees who cannot find stable employment. There’s a great deal of demand for conservative journalism among the general public, but few competent conservatives who want to be journalists given what the profession pays relative to what else smart people can be doing. Thus conservative media tends to see the rise of completely incompetent outlets like OANN, which posts fake COVID cures when it’s not arguing the whole thing is fake.

Democracy and Political Ideology

There’s a great irony here. Conservatives tend to be more skeptical of pure democracy, and believe in individuals coming together and forming civil society organizations away from government. Yet conservatives are extremely bad at gaining or maintaining control of institutions relative to liberals. It’s not because they are poorer or the party of the working class—again, I can’t stress enough how little economics predicts people’s political preferences—but because they are the party of those who simply care less about the future of their country.

Debates over voting rights make the opposite assumption, as conservatives tend to want more restrictions on voting, and liberals fewer, with National Review explicitly arguing against a purer form of democracy. Conservatives may be right that liberals are less likely to care enough to do basic things like bring a photo I.D. and correctly fill out a ballot. If this is true, Republicans are the party of people who care enough to vote when doing so is made slightly more difficult but not enough to do anything else, while Democrats are the party of both the most active and least active citizens. Yet while being the “care only enough to vote” party might be adequate for winning elections, the future belongs to those at the tail end of the distribution who really want to change the world.

The discussion here makes it hard to suggest reforms for conservatives. Do you want to give government more power over corporations? None of the regulators will be on your side. Leave corporations alone? Then you leave power to Woke Capital, though it must to a certain extent be disciplined and limited by the preferences of consumers. Start your own institutions? Good luck staffing them with competent people for normal NGO or media salaries, and if you’re not careful they’ll be captured by your enemies anyway, hence Conquest’s Second Law. And the media will be there every step of the way to declare any of your attempts at taking power to be pure fascism, and brush aside any resistance to your schemes as righteous anger, up to and including rioting and acts of violence.

There’s a way to interpret the data discussed above that is more flattering to conservatives than presenting them as the ideology of people who don’t care. Those who identify on the Right are happier, less mentally ill, and more likely to start families. Perhaps political activism is often a sign of a less well-adjusted mind or the result of seeking to fill an empty void in one’s personal life. Conservatives may tell themselves that they are the normal people party, too satisfied and content to expend much time or energy on changing the world. But in the end, the world they live in will ultimately reflect the preferences and values of their enemies.

From this perspective we might want to consider this passage from Scott Alexander, who writes the following in his review of a biography of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

The normal course of politics is various coalitions of elites and populace, each drawing from their own power bases. A normal political party, like a normal anything else, has elite leaders, analysts, propagandists, and managers, plus populace foot soldiers. Then there’s an election, and sometimes our elites get in, and sometimes your elites get in, but getting a political party that’s against the elites is really hard and usually the sort of thing that gets claimed rather than accomplished, because elites naturally rise to the top of everything.

But sometimes political parties can run on an explicitly anti-elite platform. In theory this sounds good—nobody wants to be elitist. In practice, this gets really nasty quickly. Democracy is a pure numbers game, so it’s hard for the elites to control—the populace can genuinely seize the reins of a democracy if it really wants. But if that happens, the government will be arrayed against every other institution in the nation. Elites naturally rise to the top of everything—media, academia, culture—so all of those institutions will hate the new government and be hated by it in turn. Since all natural organic processes favor elites, if the government wants to win, it will have to destroy everything natural and organic—for example, shut down the regular media and replace it with a government-controlled media run by its supporters.

When elites use the government to promote elite culture, this usually looks like giving grants to the most promising up-and-coming artists recommended by the art schools themselves, and having the local art critics praise their taste and acumen. When the populace uses the government to promote popular culture against elite culture, this usually looks like some hamfisted attempt to designate some kind of “official” style based on what popular stereotypes think is “real art from back in the day when art was good”, which every art school and art critic attacks as clueless Philistinism. Every artist in the country will make groundbreaking exciting new art criticizing the government’s poor judgment, while the government desperately looks for a few technicians willing to take their money and make, I don’t know, pretty landscape paintings or big neoclassical buildings.

The important point is that elite government can govern with a light touch, because everything naturally tends towards what they want and they just need to shepherd it along. But popular/anti-elite government has a strong tendency toward dictatorship, because it won’t get what it wants without crushing every normal organic process. Thus the stereotype of the “right-wing strongman”, who gets busy with the crushing.

So the idea of “right-wing populism” might invoke this general concept of somebody who, because they have made themselves the champion of the populace against the elites, will probably end up incentivized to crush all the organic processes of civil society, and yoke culture and academia to the will of government in a heavy-handed manner.

To put it in a different way, to steelman the populist position, democracy does not reflect the will of the citizenry, it reflects the will of an activist class, which is not representative of the general population. Populists, in order to bring institutions more in line with what the majority of the people want, need to rely on a more centralized and heavy-handed government. The strongman is liberation from elites, who aren’t the best citizens, but those with the most desire to control people’s lives, often to enforce their idiosyncratic belief system on the rest of the public, and also a liberation from having to become like elites in order to fight them, so conservatives don’t have to give up on things like hobbies and starting families and devote their lives to activism.

I’m not suggesting this is the path conservatives should take; they might feel that a stronger, more centralized and powerful government is too contrary to their own ideals. In that case, however, they’ll have to reconcile themselves to continue to lose the culture into the foreseeable future, at least until they are able to inspire a critical mass to do more than just vote its preferences.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

When the armed forces serve a global corporate agenda, it’s no surprise that HR mandates are mission critical.

Georgia shows the stakes. The GOP must blaze the way.