A reply to Professor John Yoo's and Judge James Ho's case for the original understanding of the 14th Amendment.

Voting in Prison

Granting felons the franchise will not improve the democratic process.

Two years ago, author Victor Davis Hanson published a book called The Dying Citizen: How Progressive Elites, Tribalism, and Globalization Are Destroying the Idea of America. Hanson’s title says it (almost) all: the disappearance of the distinction between citizens and legal residents, on the one hand, and the illegal immigrants who have flooded our borders under the Biden administration; the decline of the sense of common citizenship in favor of identity politics (based on distinctions of race, sex, and “gender identity”); the effective transfer of power over our lives from elected officials and those accountable to them to activist judges, along with bureaucrats who take advantage of loose Congressional statutes to make what is effectively law covering a large swath of Americans’ lives. There is one area of the decline of citizenship that Hanson’s book does not address, however, and which merits attention: the establishment of the legal qualifications for voting, which have increasingly been eroded in recent decades by guaranteeing the franchise to ex-felons.

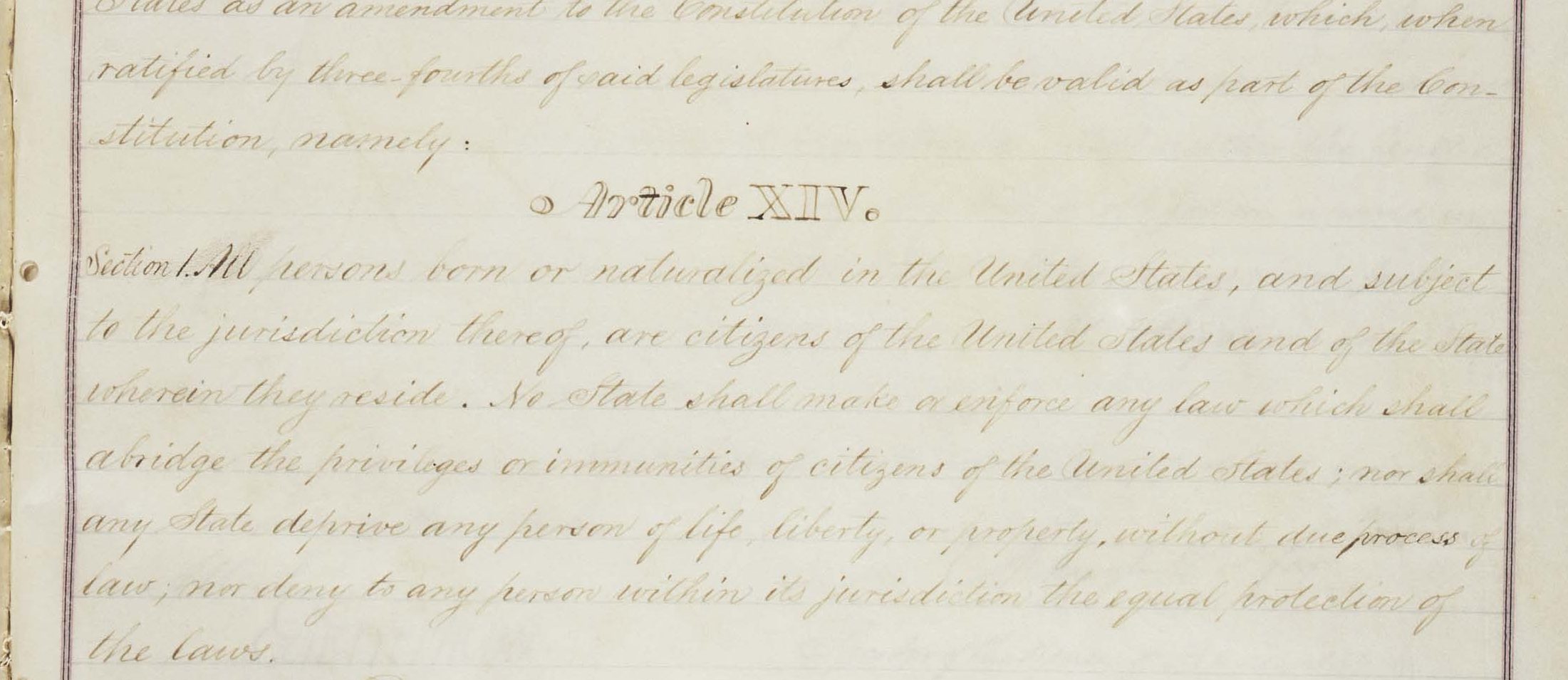

The Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution rightly prohibits the denial of the franchise to any citizen, by either the federal or state governments, “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Its chief purpose, of course, was to guarantee the right of black people, most of whom had previously been enslaved, to vote. It took a century for that purpose to be fully effectuated, thanks to the 1965 Voting Rights Act. But neither the Amendment nor any subsequent legislation required governments to allow ex-felons—those who had committed major crimes—to vote. Still less, of course, do they require that felons still serving jail time for their crimes be allowed to participate in elections. Yet while polls show that most Americans would oppose at least the latter step, such was the proposal of then-Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders in 2019—following a policy already in operation in his state of Vermont, and subsequently adopted in Maine and the District of Columbia.

The Fifteenth Amendment aside, the Constitution leaves states otherwise free to set the requirements for voters in Federal as well as state and local elections. (Early in the nation’s history, some states had moderate property qualifications, though these were soon abolished, given the new nation’s democratic spirit.) The disqualification of felons from voting is said to have originated on a wide scale after the Civil War, as a surreptitious means of eroding the Fifteenth Amendment’s guarantee against racial bias. (It wasn’t hard for racist officials in the former slave states to invent criminal charges so as to undermine black people’s newly gained constitutional rights.) But the origins of the prohibition in some states do not undermine its real rationale today.

To understand why felons (at least those who’ve committed violent crimes), either currently in prison or after their release, should not share the franchise, we need to make a clear distinction between two kinds of rights: the natural rights that inhere in all human beings, and which our Declaration of Independence holds that no individual (regardless of his citizen status) may be denied, and political or civil rights, which are the creation of government. Despite the Biden Administration’s policy of effectively open-borders, those who are neither citizens nor legal residents lack any inherent right to live in this country. Even the granting of asylum to the victims of severe oppression abroad is a matter to be determined by civil, not natural law.

Besides prohibiting the violation of any individual’s natural rights to the security of his life, liberty, property, and “pursuit of happiness,” the Declaration also holds that governments derive their just powers from “the consent of the governed.” Though the means through which that consent is to be obtained is not spelled out in the Declaration—that is a matter for the Constitution—such popular consent is chiefly a means to the securing of people’s individual rights, not an end with the same status. (Hence requiring even legal residents to undergo a residency requirement and other qualifications before becoming citizens does not violate their rights, whereas allowing them to be robbed, raped, defrauded, or murdered certainly would. And nobody seriously maintains that prohibiting children or adolescents from voting or office-holding constitutes mistreatment.)

Both considerations of justice and long historical experience justify the conclusion that beyond age requirements, government—at least in a country like the U.S. with long experience in self-government (even during the colonial period) and a tradition of law-abidingness and toleration—should not impose limits on voting based on such artificial criteria as economic status, birth, education, or ethnic background. While cases of rehabilitation are far from unknown, especially on the part of those who committed their crimes as youthful offenders, is it likely that adding the class of ex-violent criminals to the voting rolls will result in better-qualified officials being chosen, or better policies enacted, as a result of their electoral contributions?

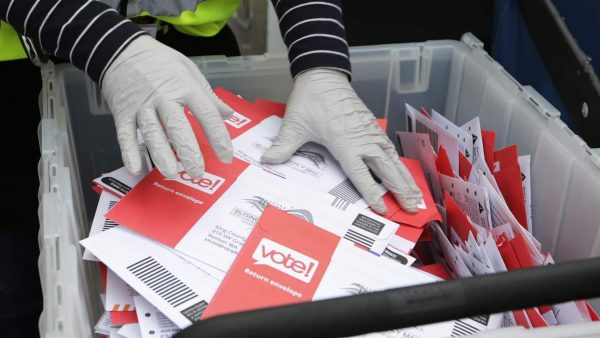

The issue of voting by felons has recently come to the fore because of competing governmental actions in several states. A year after taking office, Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin of Virginia announced that he had rescinded a policy instituted by a Republican predecessor in 2013, and then expanded to cover all ex-felons by two Democratic governors who had followed, that automatically restored voting rights to all felons who’d completed their sentences.

Meanwhile, in North Carolina, the state Supreme Court “appeared deeply skeptical” according to the New York Times of a lower-court ruling that claimed constitutional authority to restore the vote to all ex-prisoners. And the Florida legislature “effectively nullified” a 2018 citizen ballot initiative granting voting rights” to some 934,000 residents (by adding the requirement that the ex-felons “pay all court costs, restitution and other fees”). In consequence, according to the Times account, all three states were left “on a path toward rolling back” voting-rights policies “closer to where they were 50 and even 100 years ago.” On the other hand, according to “experts” cited by the Times, Youngkin’s decision is “unlikely to represent a dramatic change in the long-term trend among states toward loosening restrictions on voting by people with felony records.” While “such restrictions still deny the vote to some 4.6 million voting-age Americans…that number is down nearly 25 percent since 2016.” And Minnesota just enacted a law granting the franchise to 56,000 ex-felons, while a bill awaiting the New Mexico governor’s signature would add 11,000 to the voting list.

Why should the restoration of voting rights to those who served serious prison terms concern us? Well, to begin, recall the 2000 Florida Presidential election, in which the final outcome (and as a result the outcome of the national election) was determined by just a few thousand votes. Since felons, according to the Times, tend to vote heavily Democratic, imagine how the outcome in many state elections would change if only a significant fraction of the 934,000 ex-felons had regained the vote. Do we really want violent felons, regardless of party affiliation, potentially determining the choice of our highest government officials?

Those who favor a blanket policy of restoring the vote to all ex-felons claim that denying it to them is racist, since a disproportionate number of violent felons are black. But so are the victims of violent crime. Will granting the vote to all ex-felons, let alone those who are still serving their sentences, be likely to improve the quality of our government, including our judicial system, and thereby better secure the inalienable rights of all citizens, regardless of their race? Sometimes, as Niccolò Machiavelli teaches, what superficially looks like a policy of “compassion” or humanity is in reality one of extreme cruelty. Lawmakers, please think through your humanitarian, or partisan, instincts more fully before doing great harm to the nation and its citizens.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Who’s really suppressing the people’s voice?

A terrible idea whose time has come.