Conservatives are attacking America by weaponizing our favorite things.

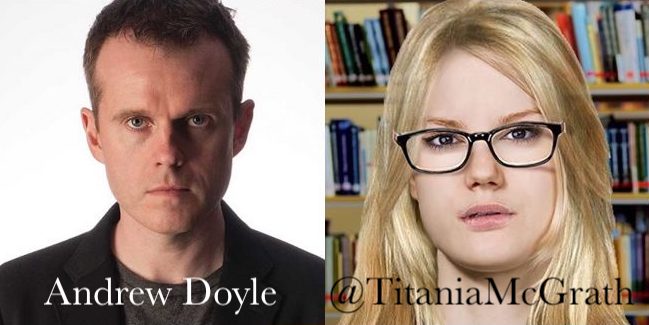

Titania McGrath and the Politics of Wokeness: An Interview with Andrew Doyle

The popular Twitter satirist and cultural commentator talks social justice, classical liberalism, and the fate of the arts in the West.

Titania McGrath thinks you’re scum. That is because of how tolerant she is.

In April 2018, Oxford-educated comedian and journalist Andrew Doyle created a satirical Twitter persona, an “activist,” “healer,” and “radical intersectionalist poet” who self-identifies as “selfless and brave.” Titania, an imaginary amalgam of all the worst excesses in the modern social justice movement, fancies herself a voice for minorities of all kinds (whether they know they agree with her or not). What she lacks in self-awareness, she makes up for in conviction.

There are other parody accounts in a vein similar to Titania’s: Jarvis Dupont of the Spectator USA, for example, or Wrightly Willowleaf (who moved to Williamsburg before it was cool). But none of them has achieved Titania’s notoriety, or her reach (418.4K followers). Doyle attributes some of this success to a much-publicized Twitter ban. But that’s perhaps too modest: Titania is a note-perfect creation, as frighteningly accurate as she is screamingly funny. “[Y]ou need to understand that which you are critiquing,” Doyle told me: more than anything, his tweets as Titania demonstrate an incisive grasp of how radical progressivism functions and why woke politics commands such hypnotic power over the 21st-century Western psyche.

Doyle is among a growing number of classical liberals who have simply had enough: witty, thoughtful, and profoundly humane, he is the kind of eloquent sophisticate who would have been quite uncontroversial as a cultural critic and public intellectual in a less turbulent era. But that wasn’t his fate. Comedy and culture have been so strangled by political correctness that he is “at that point where I feel that it would be morally wrong to be silent” about the crisis of free public discourse in the West. Still, there is much more to Doyle than politics and polemic. I spoke to him at some length about his philosophical outlook, his academic interests, and his career beyond Titania.

Spencer Klavan: Tell us the story of Titania McGrath. How did you come to be running this satirical account?

Andrew Doyle: It was April 2018. I decided to create a fake character on Twitter—a satirical character who would mock the worst excesses of the social justice movement. So, to that end, I thought one of her characteristics should be a devotion to fourth-wave intersectional feminism. In which case it made sense that she was female and white—because a lot of what passes for social justice activism is actually rich white people telling poor black people what they should be thinking. It’s a kind of soft racism, I think: a very patronizing view of minorities. So I thought she should come from privilege.

And so she’s very rich, she comes from an independently wealthy family, but she’s determined to express how oppressed and persecuted she is at every opportunity, and also to attempt to censor anyone who disagrees with her on any point whatsoever. This is the kind of entitlement and narcissism that you see among social justice activists—it’s why they’re not prepared to debate. They can’t conceive that anyone who sees the world differently is anything other than evil, and they think the world has to change around them to suit their particular preferences.

I just did it for myself, really. I didn’t expect it to take off in any way. But then it just started gaining followers very rapidly, and at some point I was contacted by my literary agent, saying that a publisher he works with was thinking about doing some kind of anti-woke book, and would I know anyone who might be able to write that? So I said, well I could, because I’ve got a character who satirizes this stuff.

And my agent was actually following Titania without me knowing. He didn’t know it was me. So we ended up with a book deal off the back of it. And then she was banned from Twitter permanently at the end of 2018. But there was a bit of an outcry from people online, various prominent conservative commentators, so she was re-instated—and that really boosted her profile. And then the book came out, so it’s been like a rolling stone, just gathering momentum.

S.K. Yes, something you capture really well with Titania is the complete lack of self-awareness, the oblivion of people to their own racism even as they criticize racism in others.

Let’s talk about that moment when Titania got banned: you’ve written elsewhere that “those in power cannot tolerate being ridiculed.” That was a theme when we interviewed Kyle Mann of the Babylon Bee as well: why do you think ridicule gets woke people so angry?

A.D. Because it’s an effective way to expose their folly. There’s something very instinctive that we all have as human beings: we don’t like being laughed at. And that makes sense: it feels like a form of humiliation. But I also think that’s why it’s a good way to puncture and deflate those kinds of pretensions. And they absolutely don’t like it—I mean, tyrants throughout history have locked up and killed satirists. We had the Bishop’s Ban on any satirical work in Great Britain, and that was in 1599. You’ve got president Erdogan in Turkey who will lock up satirists and call for their arrest—so it’s a pretty standard feature of history.

Of course, with Titania, the misinterpretation of what she’s doing is that she’s punching down, she’s attacking minorities. That’s not the point at all: it’s attacking the social justice movement, which is very very powerful but doesn’t perceive itself to be powerful. That’s why they claim victimhood: so that they can say mocking social justice is mocking the weak. It’s not, of course. It’s mocking those who are in power.

S.K. You’re absolutely right that persecution of satire by the powerful is as old as satire itself—goes back to the court of Ptolemy II, probably further. So let’s talk about power.

Based on what you’ve written it seems as if you feel that wokeness wields a kind of soft power—a cultural power more than a legal or a political power. I’m reminded a bit of Shelley’s argument that poets are the “unacknowledged legislators of the world.” How is it that you think the woke and the social justice movement came to acquire the overwhelming degree of cultural power they now have?

A.D. I think it’s because the woke movement is largely driven by people who are independently wealthy and privately educated. Just to give you an example from the U.K.: 7% of our country is educated privately. So those are the richest people, but those 7% dominate the arts, and the media, and journalism, and the law, and education, and the government. So what you have is a very small coterie of very powerful people who disproportionately control the direction of culture.

The BBC is a good example of an institution that is overly dominated by privately educated people, and it’s very very woke. So there seems to be a correlation. And similarly, the universities where they have the most woke students, and the most people wanting to de-platform and censor—which comes hand-in-hand, obviously, with woke culture—there is a clear correlation between the economic privilege of students and how woke they are. So the worst examples you’ll find are in places like Oxford University, Cambridge University, Yale, and Harvard. Those will be the ones where you get the most egregious examples of censorial wokeness. And of course those are the kids who come from the most privileged backgrounds.

It is no surprise to me that those with the most would like to claim to have the least and to be the most oppressed. There was a survey in the Atlantic about political correctness, and by a long way, the people who resent political correctness the most are the ones whom it purports to defend: the ethnic minorities and the sexual minorities and so on. And the people who support political correctness the most tend to be rich white liberals, by a long way.

I think there’s something quite strategic about holding on to power by claiming to be oppressed or claiming to stand up for the oppressed. It’s something which I think is unprecedented in history: those who claim to be the victims also seize the power. It’s very unusual.

S.K. That’s something I’d like to ask you more about: this mode of gaining power. On the one hand you suggested that there might be a strategy behind it, but you’ve also compared it to a kind of religion, as we have done also here at The American Mind. Which would suggest a more unconscious impulse, less than an explicit strategy.

A.D. Yes, that’s the theme of Tom Holland’s last book, Dominion. Holland makes that point that in the absence of Christianity, there’s something instinctive about finding these belief systems. And it does have the same hallmarks: it has the aspect of original sin, the Augustinian concept of original sin which now comes in through whiteness, or being heterosexual—having these immutable characteristics that make you a sinner. And then you’ve got the heresy concept, the idea that anyone who doesn’t think the right things is a heretic who needs to be cancelled, and then you get the metaphor of cancel culture, which is a lot like witch hunting, and burning people at the stake as the Inquisition might have done.

And of course so much of the theorizing behind woke ideas is based on entirely unsubstantiated, faith-based positions. They believe in unconscious bias, and institutional power structures—things that you can’t quantify or put your finger on that just sort of exist in the ether like spirits. And to ask them to prove any of these positions is to simply get the response that well, they do exist because we know they do. Which is what a religious zealot would say.

So I think that certainly the best way to understand the social justice movement is to see it as a cult. Because then it all makes sense, and it also makes sense why they’re able to behave so barbarically toward those who don’t subscribe to their belief system. Because the hallmark of many religions is tolerance to a degree. And then where things start going wrong, where witches start getting burned at the stake and heretics start getting executed is where that tolerance runs out. And I think that’s what happened here: the social justice movement is a fundamentally intolerant movement. And fundamentally illiberal. There’s nothing liberal about it.

S.K. You mentioned Tom Holland, and someone else who springs to mind is your friend Douglas Murray, who in his latest book The Madness of Crowds has this thesis about “grand narratives.” He argues that all our major religious narratives and other political narratives collapsed over the course of the last century, and into their place stepped a kind of mass psychosis.

I’m not sure how confident Murray is that those dead narratives can be resurrected—do you think there is some other, more healthy totalizing system through which we can view the world? Something that can defeat and take the place of wokeness?

A.D. Yes, I’d call it liberalism. And I mean that in the classical sense of the word. The best way to build a humane society is from the liberal position: everyone is free to say and do whatever they want to do, to identify however they want to identify, to live their lives as they want, so long as it does not encroach on the freedoms of others. And that strikes me as the most sensible solution to anything.

So if you take the trans debate, the liberal position is that anyone has the right to do to their bodies whatever they want, to call themselves whatever they want, but they have no right to demand that others would use the language that they would like them to use. It has to be about individual freedom, and that strikes me as the best way to run a society.

S.K. Let me press you a little on that. One of the issues that arises with liberalism as you articulate it—has done since John Stuart Mill, at least—is that there are always limits to individual freedom.

And whereas I’m sympathetic to what you’re saying, I also think that it’s important to specify those limits in a systematic way. Mill for example mentions that you could rightly stop a man from walking on a bridge that was known to be unsafe, if you knew that he was unaware of the danger and didn’t mean to incur it. Or there’s that Chesterton line: “there is a thought that stops thought. That is the only thought that ought to be stopped.”

A.D. But that’s still a liberal position. That’s not an imposition from an external force: we all self-censor to a degree, we all think about what we’re saying, or at least we should. But that is not incompatible with a liberal worldview, because you are making the decision for yourself. I think the limits that you describe are all pretty much covered by that caveat: “so long as whatever you are doing does not encroach on the freedoms of others.” That, I think, covers pretty much everything—I mean that would cover, for instance, libel laws. Perjury. Harassment. That kind of thing.

Unless—can you give me an example of something that isn’t covered by that principle?

S.K. Well, that Chesterton quote that I just mentioned, for instance: the “thought that stops thought.” The notion that you might prohibit people from expressing anti-liberal ideas is more extreme than the notion that you might prohibit them from enforcing anti-liberal policies. Do you think we should go so far as to make certain ideas off-limits if they threaten the very institution of free thought?

A.D. Within a liberal system those sorts of things happen naturally. Part of freedom of speech is the freedom to criticize the speech of others. So when, as a society, you reach a point where using racial slurs is collectively frowned upon—that’s been reached by negotiation and agreement among people—it doesn’t mean that you don’t have the right to use such racial slurs and epithets. But you do so under the awareness that when you do it you’re likely to get criticized and there’s likely to be opposition. Which strikes me as perfectly reasonable.

You know, I’ve never suggested that freedom of speech comes with freedom from consequences. I think consequences are a good thing: so long as those consequences aren’t the state locking you up, or arresting you, or any violent repercussions, then I’m happy with whatever consequences come from speech.

But I think people should have the right to choose for themselves how they express themselves, and what thoughts they censor—because that’s up to them, ultimately. But I also believe in encouraging people to tell the truth and not to self-censor.

S.K. I’m interested in that concept of self-censorship, which I’ve read you on before. You wrote a piece for Sp¡ked in defense of a better sort of political correctness—a more civilized kind—that prevailed during the ’90s. If self-censorship is an important, even a crucial mechanism for the kind of liberalism you’re describing to work, and if self-censorship is also our problem at the moment…

A.D. Well I think the problem comes with using that term, self-censorship, to apply to both things. I don’t think what I’m talking about there is self-censorship. Because censorship implies against your will, or that it’s not good for you. In other words, it implies that you really want to say something, but you don’t.

That’s when you self-censor: when you really really want to say what you perceive to be true, but you stop yourself for fear of what might happen. But it’s not self-censorship to be discerning. I don’t think it’s self-censorship to think about what you’re saying: is that a wise thing to say? Not because of consequences, but, is that accurate? Can I be sure of that? Is it polite, is it tactful? That strikes me as a good thing.

I don’t think that’s self-censorship really, it’s just choosing your words with care, which I would encourage everyone to do.

S.K. It sounds like discernment and self-censorship are sort of the light and the dark side of the same thing for you—the good and the evil version, respectively, of one impulse. Is it true, do you think, that our collective discernment has become corrupted into self-censorship, and if so why?

A.D. I suppose it’s because we’re living through a period where people are very literal-minded. So comedy suffers, and metaphor suffers. And because so much of the woke ideology is grounded in this sort of post-structuralist idea that with language comes power. In other words, certain forms of discourse normalize hate, or normalize oppression.

And therefore there is an impulse to critique people’s language too severely on the basis that certain forms of expression perpetuate these power structures. Of course, that is again a faith-based position which doesn’t have any merit. But if you are attempting to encourage self-censorship on the basis of a flawed premise such as that then there are all sorts of problems.

Healthy criticism is a good thing for all of us, because it makes us reflect on what we’re saying, and the accuracy and validity of what we’re saying. But we don’t live in a culture in which criticism is of a particularly high standard. Particularly cultural criticism—the commentariat in the media—are fighting with these ghosts of their own imagination. They’re perceiving racism, homophobia, sexism, transphobia, where they don’t even exist. So that standard of criticism is very poor, and it does have an effect on people, because it means people are nervous about making legitimate points for fear of a backlash.

S.K. So would you blame Foucault and the post-structuralists for this, ultimately? Is that where things took the wrong turn intellectually for the West?

A.D. I think they didn’t help. I think what didn’t help is that people took them too seriously. It was a fad which should have passed. And it did pass for a while: it became very unfashionable in academia over recent years. When I was in academia Foucault was very fashionable, then he went out of fashion and sort of died off, and then he went into the mainstream.

But the mainstream understanding of Foucault is very weak. Whereas those who have read him will know that he wasn’t a great historian by any means, and certainly not the great thinker that he is esteemed to be. And those who now talk about power structures—it’s only very tangentially related to what Foucault was saying, really.

But that fundamental premise—the idea that there is no truth beyond the language with which it is expressed, which is that kind of fundamental post-structuralist idea that you get in Derrida and the like—is what informs a lot of the censorial aspects of social justice culture, and what I’d call the identitarian Left—the Left who have accepted identity politics.

S.K. Yes, it’s remarkable to me how poorly-digested most academic influences are at this point. Not only Foucault and Derrida, but even Nietzsche and Marx show up in these barely-understood forms—

A.D. Not barely-understood at all: they don’t read them. They read about them. Even when I was at university and Foucault was the thing, very few people actually read Foucault. They’d read David Halperin writing about Foucault or something. I mean, Halperin wrote a book called Saint Foucault, for fuck’s sake, you know, writing about him, and people would read that and think that they understood Foucault.

But I had to wade through that bloody History of Sexuality…awful. That’s the one where Foucault says that the idea of homosexuality didn’t exist before the term was created. It’s a nonsense.

S.K. What was your academic experience like in that regard—were you encouraged to engage directly with primary texts?

A.D. Well, I had to, because the first chapter of my doctoral thesis was a repudiation of post-structuralist thought. And I had to for my undergraduate degree anyway, because it was so much the fashionable thing. My master’s was a more historically-grounded dissertation, so there was less of the theory in that. But then for my doctorate I was trying to suggest that discourses of sexuality are not dependent on language, and can flourish even if the language is not there to express the desire.

So I read the post-structuralists because I felt I had to. I think you need to understand that which you are critiquing. That’s a fairly basic idea that unfortunately a lot of people don’t grasp…they go out all guns blazing about something they don’t really understand. I don’t value any opinion unless it is an informed opinion.

S.K. Let’s talk a little bit about where this intellectual journey has ended you up today politically. You protest a lot that you’re not conservative, you’re not on the Right. You’ve already articulated some ways in which that’s true: in fact what you are is a classical liberal.

But as you’ve also written, and as many of us are feeling at the moment, political coalitions are shifting around us: you’ve said that censorship, for example, has migrated from the Right to the Left. Do you define yourself politically in any way, and if so how?

A.D. Well I don’t consider myself ideological. I’m not interested in an ideology which will tell me how to think about everything. I’m interested in considering things, and thinking about ideas, and coming to conclusions without being sort of cattle-prodded that way.

In the question of where I stand on the political spectrum, I think there is an objective method of assessment which I can do nothing about: I think if you were to write down all of my political views on various things I would come out more left-wing than right. Certainly in terms of economic principles I’m more to the left, in terms of welfare, in terms of nationalism: I understand nationalist sympathies but I don’t feel them personally. That’s more an instinctive thing, but that definitely pushes me more to the Left as well.

I’d say I’m quite culturally conservative, however. I believe in high standards of education, because I think that adult autonomy depends on effective socialization in youth. So you need to have a rigorous school system, and children need to have an awareness of the classics and be taught the classics. I think art history, for instance, should be embedded at a primary-school level: not “let’s see what you can create with these paints”; I think you need to learn the classics. That’s a more traditionally right-wing viewpoint. I also believe in politeness, and decorum, and high standards and that kind of thing, which I think might be more associated with the Right.

But then, you know, someone like George Orwell was a cultural conservative. His essay “The Lion and the Unicorn” is a robust defense of cultural conservatism, but at the same time he’s very much on the Left. He’s actually a sort of canonized figure of the Left, so there is room for cultural conservatism within traditionally leftist thought. I don’t think one excludes the other.

So, in a way, I haven’t told you what I am. It’s because I don’t care about Left and Right anymore. Those things don’t interest me. I care about the ideas and the debates, and labeling oneself isn’t helpful particularly.

S.K. I don’t think you’re alone in wanting to shrug off those frameworks. And I think one of the most disorienting things about our present moment is that baseline issues like civility—which used to be common patrimony of both Left and Right—didn’t really used to be up for debate. So at the time it would have been perfectly natural, in a way, for Orwell to write that essay. But now it makes both him and you into somebody people might label conservative when politically you might not be.

You’re touching upon something that fascinates me, though, which is the kind of trickle-up effect from soft power to hard power. It goes back to Plato at least, and Aristotle picks it up in a big way: the educational and cultural work that you’re describing, and the way that we conduct ourselves in comedy halls, and so on, ultimately maps onto the way that we conduct ourselves in Parliament and at the voting booth.

Is the kind of fight that you’re fighting related to a political change that you hope is on the horizon, or do you consider the two spheres completely separate?

A.D. Well, I’m talking about the culture war, which does overlap with the business of government. But, I mean, I didn’t vote in the last election: I tore up my ballot paper, because I don’t feel that there is a current mainstream political movement that reflects where I would like to see society headed.

And I think the culture war is part of that. Let’s not forget, the Gender Recognition Act in the U.K. came through the Conservative party. And that’s very woke legislation. So, I think it’s in the interest of people on the Left and the Right to eliminate woke culture. Because I think it prevents us having a sensible adult discussion about what needs to be done societally. It infantilizes the entire political process, and the people within it, and makes it less effective.

So I think the Left and Right should agree on the basic liberal principles of free expression, free discourse, and free thought. But also we need a shared social contract of how we address each other and how we tackle these issues. It doesn’t work if one side of the debate is just screaming and covering their ears. Nothing can be achieved that way.

S.K. It’s a tremendous challenge, the screaming and ear-covering. And again it has ancient precedent: some of the first words of the Republic are “can you convince us if we won’t listen?”

Do you find yourself in your own life engaging with people who simply will not listen or engage with you? If so, what is your approach?

A.D. I will engage with such people only for so long. Because all I can do is express what I believe. If the person I’m talking to insists on misunderstanding my view, mischaracterizing my view, willfully or otherwise, and ascribing views to me that I do not hold—if that is happening, then there can be no further discussion.

So I will put an end to it. I’ll try and give people the benefit of the doubt, but if that persists then I’ll just walk away. Because you cannot engage in a discussion with somebody who is arguing against himself, who is arguing against a fantasy of his own creation. There’s absolutely nothing you can do there.

So I think one of the first things you have to do is be discerning about who you talk to. You know, let’s have the debate with those who are willing and capable of debate, and let’s all agree that those who are incapable of debate should be ignored, because they won’t have anything to add. And then we raise the bar of political discourse.

But we have major mainstream politicians saying these ridiculously woke things, and saying these incredibly intolerant things, and calling people Fascists and Nazis and things like that. When that’s happening, it’s like debating a child. It’s not going to achieve anything. So we basically just need adults back in the game. We need the adults to take control.

S.K. Has this dynamic changed for you since you were “outed” as the creator of Titania? It wasn’t intentional, and now you’re sort of known as this gadfly. What’s life been like since then?

A.D. Well, I was already writing for Sp¡ked, and my ideas were out there. They got a certain degree of flak, but I think what Titania has done is just drawn more attention to my ideas. And that means that inevitably I’m now fending off more aggressive attention than I would like.

But I suppose that’s part of it: if you say something that people perceive to be controversial then they’re going to react. For the record I don’t think anything I’ve ever said is particularly controversial. But it’s treated as such by those who fail to understand what I’m saying.

S.K. Yeah, you wrote just recently that you might have to retire Titania…

A.D. Well, I was part joking. I was talking about the way in which she’s taking over my life so I may have to kill her off. It was a quip.

That said, I don’t want to be focused on one character for too long. I’ve just written another book as Titania, and I suspect that that will be the last book I write as her. If I do more with her I will have to develop the character into some other realm—televisual, maybe.

So I was half-joking when I said that. But there is an element of truth to it insofar as I don’t want to be doing this forever.

S.K. Do you think she’ll have a life of her own if you turn your attention somewhere else?

A.D. No, she’s an alter-ego, so if I neglect her she’ll wither and die. And that’s fine. I mean, the next thing I want to do is write a non-fiction book about the culture war, which I will do. And that won’t have anything to do with satire. It might mention satire, but it won’t be a satirical piece.

At the moment that’s what’s driving me. And I’ve got another few projects on the go: I don’t want to become obsessed with Titania. And actually there comes a time where I get bored of the culture war fight. It is exhausting, and I don’t want to just focus on these issues. I think they are very important at the moment, and that’s why I do it, but I don’t want to become a complete monomaniac.

S.K. No, and you obviously have much more to offer. If you had your druthers—if you weren’t in this fight to the death with wokeness—what would be your passion project?

A.D. I think I’d be writing more about the arts, and more about literature. Those are the things that really get me excited. I’m not a scrappy person: I don’t enjoy confrontation. I don’t revel in it. And so it’s a kind of unnatural fit for me, getting into all these arguments all the time. It’s not something I would want to do forever.

But I’m also at that point where I feel that it would be morally wrong to be silent on these issues. I think there’s an obligation on all of us to speak out about it, because a lot of the problem we’re getting is from people’s fear of expressing skepticism about this new ideology.

S.K. We don’t pick the moment we’re given. One of the great tragedies of wokeness is the stranglehold it’s put on our cultural life. Is there anybody you’re following, though? Anybody that, whenever they produce some new work of culture, you consume it?

A.D. Oh yeah. There’s plenty of people like that. Whenever Kazuo Ishiguro comes out with a book, or Salman Rushdie, I will read them. I mean, on the whole, my favorite writers and artists are long dead. But there are some contemporary writers that I do really enjoy, and I do seek out their work whenever they produce it.

And there’s an infinite number of things that I haven’t read that I want to read. There are infinite things to discover from the past. In many ways I think my favorite authors—people like Stella Benson and Forrest Reid—there’s more people like that, who are undiscovered, people don’t know about them, but they produced some incredible work. I want more time to explore and read works by those kinds of people.

S.K. Out of professional interest, do you ever watch Ilana Glazer, Hannah Gadsby—these hyper-woke comedians? Or do you just stay away because they’re too appalling?

A.D. No, I do watch them. I don’t enjoy their work, but I think it’s important to be aware of developments in the arts and, again, to be familiar with the thing I’m critiquing.

I don’t enjoy performances that are labeled as comedy that are not in any way comedic. They are propagandizing. That isn’t interesting to me artistically. In fact, generally speaking, I balk at art that is overly politicized. I don’t think that art needs to have anything to do with morality.

Not to say that art cannot address moral issues or political issues, or that I don’t enjoy such works. But the things I enjoy the most tend to be apolitical, amoral. I don’t want art to teach me a lesson about ethics. In fact, moral ambiguity is something that I think is really interesting in art, and really enjoyable.

I just don’t like didactic art. I find it banal. I suppose that’s a sort of personal preference: I don’t think the artist has any moral responsibilities whatsoever. Other than as an individual in society—I’m not giving them a free pass to behave terribly—but in terms of the creation of their artwork.

This is why when films are criticized for not being sufficiently representative, when Quentin Tarantino was criticized for not assigning enough lines to Sharon Tate’s character—the Margot Robbie character in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood—and you think, this is not how art works. You don’t devise a number of lines equally between all the representative figures. It’s not written by a machine.

I wrote an article about Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, where I made the point that part of what Tarantino is doing in that film is to restore Sharon Tate to the status of a Hollywood icon, a status that she was not permitted due to the activities of the Manson family. And part of lending her that iconic status is that she doesn’t speak. You see her walking around, and there’s an air of mystery about her. Had she been talking all the time, that effect would not have worked.

Anyone who’s criticizing that movie on the basis of “how many lines does the woman get to say” is frankly ill-equipped to be a film critic. They’re simply not qualified to do that job, and I don’t think we should take them seriously.

S.K. It’s a good example of the breakdown in metaphor you were discussing earlier, the hyper-literalism of our age. And of course if you’re reading from an ideological script you’re ipso facto ill-equipped to let an artist teach you something.

A.D. Well, it’s worse than that: artists are curtailed by what the commissioners demand of them. The gatekeepers of Hollywood and television are so super-woke that it will constrain what artists can create. It doesn’t affect someone like Quentin Tarantino, who is so established that he can do whatever he wants. But it does affect people who are trying to get into the business and into the industry.

This is why the state of comedy in the U.K. is so terrible at the moment: because all the major satirical television programs are not satirical. They’re just reiterating woke talking points. That’s all it is. How someone can flourish as a free thinker in such an environment is beyond me.

S.K. Well, you have a project of your own that seeks to redress this to some extent: Comedy Unleashed is sort of about that, no?

A.D. Yeah. Comedy Unleashed is a comedy night we set up in order to generate a new alternative comedy movement, to counter what was going on in the industry and to say that comedy isn’t a safe space. You shouldn’t be risk-averse as a comedian: it’s not good for the art form. But it’s been very successful, and I think that’s because there is this appetite for it.

S.K. Is a certain amount of pain, or openness to pain, just an inescapable part of being in the audience for comedy?

A.D. Yeah. The potential for offense is always going to be there, because at any point a comedian could touch on something that’s particularly sensitive to you. But of course it’s got nothing to do with you: it’s not about you. It’s about him or her on the stage.

That is always a risk, but that is also a risk in life, isn’t it. We all go through traumatic experiences, and there will be some phenomena that will remind you of those experiences. That’s the cost of living. You can’t shield yourself from such things.

And indeed those who are experts on trauma unanimously agree that the worst thing you can do is to shield yourself from any kind of potential triggers around a particular idea. You know, we all get it: when you go through a difficult breakup, you find that the music you used to listen to with your partner suddenly becomes painful to listen to, so you don’t listen to it anymore. Those sorts of things seem fair enough.

But you also can’t expect that no one else in society ever plays that music again for fear of hurting your feelings. If you feel that you are likely to be upset by a comedy gig, that’s fair enough. I don’t have a problem with that: then don’t go. That’s fine. What I fear is what’s happening now: those people who tend to be offended by certain jokes will demand that the jokes are not told rather than simply register their disapproval, or just leave, or try and not be part of it.

It’s a very narcissistic approach to living, where you say everyone else has to revolve around you. I’m not going to be part of that. There are certain jokes and things that I probably wouldn’t like, probably would find offensive. So I just wouldn’t go see those comics. Simple.

S.K. As you say, it’s a terrible disservice to people to construct the world around their own insecurity, since inevitably that project will fail and then they’ll be ill-equipped to handle themselves.

A.D. Well, it has to fail because there are billions of people on the planet, all with different sensibilities. It’s just not going to work.

S.K. And thank goodness for that.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Constitutional government demands a free but responsible media.

It’s hard to keep up.

We should seek to rebuild the standards of civilized society.

When the war against wokeness is over, our common culture could be history.

The Left is outraged by Sound of Freedom.