Loving everyone equally means loving no one in particular.

The Babylon Bee: An Interview with Kyle Mann

The Editor-in-Chief of the viral satire website tells his story, addresses factchecking controversies, and explores the philosophy of the Bee.

“The Babylon Bee is the world’s best satire site, totally inerrant in all its truth claims.”

That is the first sentence of the Babylon Bee’s About Us page. Like much of the Bee’s content, it is the result of careful thought refined into sardonic pith. Read the joke closely: it’s a diptych, a one-two punch. The first clause takes care to proclaim outright that the site contains satire. It is not a real newspaper and disavows all claim to be anything of the kind. The announcement is calibrated to declaw the media gatekeepers and fact-checkers—chief among them Snopes, Facebook, and now CNN—who have done their best to accuse the Bee of intentionally deceiving its readers.

But the Bee’s creators are not content to start their introductions with a bureaucratic caveat: that would mean letting the killjoys win. So in the second clause they undercut their disclaimer with a wry and patently absurd claim to total inerrancy. Theologically literate readers (of whom the Bee counts many among its most loyal fans) will notice here a reference to the doctrine of biblical inerrancy, a hallmark of Reformed Protestantism and other major Christian traditions.

That pretty much sums up the Babylon Bee: they’ll button up and shake your hand, but they’re damn well going to do it with a joy buzzer. And they’ll manage a perfectly-pitched inside troll about Christian culture in the same breath. The site launched in 2016 as a small backyard venture. Since then, under the leadership of CEO Seth Dillon and Editor-in-Chief Kyle Mann, it has succeeded beyond its creator Adam Ford’s fondest hopes. It boasts over 341K Twitter followers, 6.5K Facebook fans, and a kind of audience devotion that the digital age has usually reserved for makeup tutorials and PewDiePie videos.

The Babylon Bee resonates with an enormous and enormously underserved audience: conservative Christians and their allies. This much-beleaguered readership is so often the object of sardonic ridicule that it has almost forgotten what it feels like to be in on the joke. In the Bee, traditionalists (and anyone who doesn’t want to see traditionalists chased out of the public square) have finally found a brand of smart, trendy irony that speaks to their concerns. It’s a feeling, as Mann himself puts it, of “hey, this is humorous and doesn’t hate me!”

Which is also why, when Snopes and CNN have tried to defame the Bee, fans of free speech everywhere have rallied to the site’s defense. “Snopes was kind of that annoying guy at a party, who’s like ‘actually that joke isn’t true!’” says Mann. Accusations of deceit look ludicrous when levied against headlines like “CNN Purchases Industrial-Sized Washing Machine to Spin News Before Publication.” And charges of intolerance or “punching down” have largely fizzled as the Bee (which in fact takes shots at everyone, in the tradition of the best satirists) has stood strong against SJW criticism.

The Bee, in other words, has arisen as a digital-age champion perfectly equipped to puncture the pretensions of the woke mob and the deep state, all while laughing uproariously, even defiantly, along with its delighted audience. In my conversation with Kyle Mann last week, he told me more about how he and the Bee have managed this feat in an increasingly perilous digital landscape. The transcript of our conversation appears below.

Spencer Klavan: Tell me a little bit about your own personal background. How did you find your way to the Bee, and what were you up to before this?

Kyle Mann: I was actually a full-time salesman in the construction industry in 2016 when the Babylon Bee launched. I’d been doing that for ten years or so, and helping to pastor a small church down in San Diego. I grew up in the church, which gave me a good understanding that helped us to do a lot of Christian and church satire.

So, Adam Ford, the guy who founded the site, put a call out on Facebook for writers. He’d launched the site with 15 articles or so. And I clicked through, looking at them, and it really resonated with me. I really understood what he was trying to do: I’d been a fan of the Onion for a long time, and it was right up my alley to do that wry, tongue-in-cheek humor.

I’d written in the past for video game websites, and board game websites, believe it or not. So I kind of knew how to hack out a lot of material in a short amount of time. That’s really essential for the kind of fast-paced satire that we do. I just emailed [Ford], and he ran the first piece I sent, and that was the first big piece that went viral on the Babylon Bee. And so he asked me to keep writing, and a couple years later I managed to quit my construction job and do this full time.

S.K. That’s kind of a dream come true.

K.M. Nothing I was looking to get into, but here I am.

S.K. Tell me a little bit more about what resonated with you when you first saw the Bee.

K.M. It reminded me of stuff I’d liked in the past, even before the Onion, with what the [Christian satire site] Wittenberg Door was doing back in the ’70s and the ’80s. But the Bee was doing it in a way that got on top of things a lot quicker than satire sites could do in the past. Even the Onion had to adapt in that direction, because they were a print periodical and now they have to be a lot more on top of it just because that’s the way people consume news now.

Christian comedy has always bothered me, just in that it’s…not funny! You know, it’s all light-hearted. And there’s a place for that, but before the Bee nobody was saying, let’s call out Joel Osteen, let’s call out the prosperity gospel guys, let’s call out heresy, and trying to do it in a way that wasn’t like, “let’s write a 5,000-word thinkpiece on this that nobody’s going to read or share.” But instead it’s like, “let’s do this with a cutting headline that maybe a lot of people will see.” And then, if they want to go dig into the “real” sites that have actual criticisms, hey, maybe we’ll get somebody interested in that.

S.K. So then do you get attacked for being too mean? You do hit some of those heresies pretty hard.

K.M. We definitely get that criticism, but it comes from a particular group of people. They tend to be progressive, and they tend to be a vocal minority. Because most of the progressive people that I know personally—they follow the Babylon Bee. They understand what we’re doing. Maybe we hit their side a little harder just because nobody else is. But I’ve kind of been surprised that most people seem to understand. I’ve talked to far-Left people, and Christians that are on the Left—I’ve talked to people from churches that we’ve done satire on! And most of them are laughing about it. You’re only gonna have that small group of people that can’t laugh at themselves that are really gonna be upset.

S.K. You have a reputation for a no-holds-barred approach: you hit the Right and the Left, you hit Christians from all sorts of different denominations. But you also come across as having a very definite point of view: you’re a conservative, Bible-believing Christian site. Do you guys have a governing philosophy that you’re dedicated to expressing?

K.M. I think just organically, we’ve found like-minded writers who understand what we’re doing. And we do have doctrinal disagreements among the writers, and political disagreements. But I think we all understand that there are certain lines we wouldn’t cross. And that’s one of the main distinctions between us and something like the Onion. The Onion is written from an atheistic perspective, and a nihilistic perspective. Deconstruct everything: that’s the goal. And for us, well, we want to deconstruct some things. We want to deconstruct false things, and we want the true things.

So for instance, we all believe the Bible is true. And maybe some of us have a different definition of what that means, but we all agree on that. So we would write satire about how some Christians are hypocritical in that belief, or about wrong interpretations of the Bible—say people who think the Bible has guaranteed that America some kind of contract with God. We’ll make fun of that, but we won’t make fun of the idea that God has spoken to us through the Bible. We want to cut away the false traditions with satire, in order to kind of expose the core truth. That would kind of be the line: there are true things that we won’t make fun of.

S.K. You know, I’ve noticed that as a governing theme for you: you talk a lot about truth as the goal and purpose of satire. I don’t know if that’s what would spring immediately to mind for everybody. Can you talk a little bit about why you think satire’s a good vehicle for truth, and why truth makes good satire?

K.M. Satire is humor that cuts, and it cuts close to the truth. I think what really works about it is that it cuts through noise so well. As I said before, if there’s something you could say in a 5,000-word thinkpiece, but you can get at that in a ten-word headline, that’s so much more effective and efficient. I’ve said in the past that satire is truth-adjacent: you’re writing something as though it’s true, but it’s not true, and it’s acting like a distorted mirror—a funhouse mirror. It’s exaggerating some things and de-empasizing others, and in that you can see some kind of reflection of the truth. That’s how it works.

S.K. Are there models for that, and for your project, in Church history? Do you look to Church Fathers, or to moments of Scripture, that use this kind of funhouse truth-telling?

K.M. It’s been used effectively throughout not just Church history but human history. You can go back to the prophets, and see how they spoke to the prophets of Ba’al that were trying to get their god to come down, and they’d say “well maybe your god’s using the bathroom and that’s why he can’t come down.” You can look at the prophet Isaiah, who writes about idols, and he says, you chop down a tree and now you’ve got a log—how do you know which side you’re supposed to carve into an idol and which to throw into the fire? So you can look at biblical examples, you can look at Jesus—he uses satire in his parables.

And going down through the ages, you can look at John Bunyan, who wrote Pilgrim’s Progress—there’s a lot of funny stuff in it that holds up a mirror to how Christians live their lives. You can look at Martin Luther, who just absolutely savaged his theological opponents, and then you can look at guys like C.S. Lewis with the Screwtape Letters, G.K. Chesterton and a lot of his works. I think every age is going to raise up people who want to communicate truth in the way that God has gifted us. And for us it just happens to be humor and satire.

S.K. I was wondering as a reader: I feel as if I’ve discerned a shift. Initially the Bee published a lot of inside-baseball Christian jokes about church life and Christian disagreements. Then I got the sense that you’ve kind of moved over time toward more political headlines. But I’ve heard your CEO Seth Dillon say that’s wrong—that you guys have basically stayed consistent throughout your history. What do you think about that, and what might be giving the impression of a shift?

K.M. There’s a few different elements there. On the one hand, sometimes people start out with a faulty premise, because almost half of the articles that we published on launch day were political, and not Christian at all. I think we were writing satire of the church where Christians, who kind of tend to be conservative, were reading it and going “hey, this is humorous and doesn’t hate me!” And they were sharing it with friends, and that audience built up.

Then, just over time, as our political articles started getting shared much more widely, the market for that kind of stuff is a lot bigger on social websites. But we actually still do a lot of church humor and inside baseball jokes. I think just the other day we published two or three of those.

But the problem is, we also publish a lot more content now. The Babylon Bee used to be me and Adam working out of our garages part time, and we had time to get two or three articles up in a day. So now we’re publishing six or seven in a day. And if we publish two or three Christian articles as usual, and then we publish three or four political ones, well, people share the political ones a lot more. So that’s just what you see in your feed. I think also maybe the material that was ripe for picking in the church—we hit all the low-hanging fruit, until now we’ve got to work a little harder to get the church jokes up. Whereas current events are kind of a bottomless well of material.

S.K. Now that you’ve grown so much, you guys have a whole staff of writers. What’s your process like? Do you toss ideas back and forth amongst each other or work solo?

K.M. It varies a lot. Sometimes there’s a kernel of an idea someone has, then I’ll edit it and change the exact wording or the target. Sometimes It’s super collaborative, someone will have something and then another writer comes along and punches it up, and someone else writes the body—it’s all done online, in a Facebook group. I would say most often it’s probably just me sitting at my keyboard and pressing keys until something funny comes out.

S.K. You mentioned that there’s some denominational diversity and political diversity among the staff. Are your writers from a lot of different backgrounds? Are they all lifelong Christians?

K.M. They’re mostly all Christians. We have a couple of people in our writers’ group who’ll come in and pitch who aren’t necessarily Christian, more on the political side. But 95% of us are Christian for sure. Mostly protestant, a couple of Catholics.

S.K. How about educational backgrounds?

K.M. I did a couple years at the Master’s University in California, a private Christian college. Frank Fleming is one of our more prolific writers, and he’s actually a software engineer, and then Seth our CEO has got a bachelor’s in business management. It varies, but most of us have to check off the “some college” box.

S.K. We’ve gotta talk about fact-check-gate. You guys have sat through innumerable waves of hostility. You’ve got Snopes fact-checking you, now CNN reporters and even former CIA analysts. Christian publications like Christianity Today and Relevant Magazine have jumped on the bandwagon. As I gather, the accusation is that you’re all part of a conspiracy to mislead people into believing fake news. Then that gets assimilated into an ecosystem of allegations about fake news sites helping deceive people so President Trump can get elected. Is that a fair assessment of your critics’ argument? And if so, what do you typically say in response to charges like that?

K.M. Well, our satire has been fact-checked by Snopes many times, and that goes back to 2016. Mostly the political articles but sometimes the Christian articles. And it was never really a concern of ours, because we felt like it indicated effective satire, when satire cuts that close to the truth. Now obviously there’s a line—there’s a distinction, because there are fake news sites that just write things like “can you believe this horrible thing Hillary Clinton said?” And there’s no joke, there’s no punchline, there’s no point. It’s just trying to get outrage clicks. So when we write something that could be misconstrued, it’s constructed in a very specific, deliberate way, to try and indicate that it’s a joke.

Especially when it gets shared outside of our circles. I think the majority of the time when we get fact-checked, it’s because somebody like Ben Shapiro will come along and share one of our articles. And then his audience is like, “I can’t believe this!” Whereas people that follow the Babylon Bee get it. So it was never a concern of ours.

But the first time we kind of raised the red flag was in March 2018, so almost two years ago. There was an article we wrote that said CNN was spinning the news in a big washing machine. And that got fact-checked by Snopes, you know, “no, CNN do not spin their articles in a washing machine.” And it made us laugh to think that someone might actually have misunderstood something like that. But we’ve still never seen evidence from Snopes that anybody actually did believe the article. I think it might’ve just been getting shared a lot and so they decided to check it.

And so then we got a message from Facebook the next day saying, you shared known fake news and your page will be de-platformed if you continue. And that was really concerning for us, but luckily we managed to get some publicity out of it and Facebook backed off. And I don’t think Snopes is their fact-checking partner any longer, so that threat kind of went away. But just recently we did that article about Georgia State Representative Erica Thomas, who said some guy told her to go back to her country. And we said she’d been to Chick-fil-A and the server said “my pleasure,” and she said “what do you mean, go back to my country?” Our audience loved it, and then Snopes published a fact-check.

And that’s when they kind of shifted from “this is just satire” to “the Babylon Bee is intentionally deceiving people.” They filed us under junk news, and the article they wrote was really horrible. We had our lawyers contact them, but they didn’t really back off. They kept doubling down on it with other posts. They had a study commissioned to say that we are the most deceiving of the satire sites—it was kind of a junk study, the methodology was really flawed.

But after that they kind of kept taking the L on social media. Everybody was just destroying them, because everybody got it that this was a joke. Snopes was kind of that annoying guy at a party, who’s like “actually that joke isn’t true!” And everybody kind of slammed them for that. They kind of came off as humorless and not really understanding, but after that they fact-checked us a couple more times. They do call us “labelled satire” now, instead of “false.” But it’s still kind of a weird label because it’s like they’re saying, “well, this site says it’s satire but we just don’t know,” you know…it’s like what Relevant did—they called us “satire” in scare quotes.

S.K. Well you’re very generous to attribute this stuff to misunderstanding. And there’s definitely some cluelessness involved. But I can’t help wondering whether there’s some more pointed hostility here, because they just can’t stand conservatives making fun of liberals effectively. To what extent do you think this is a concerted attempt to shut you down?

K.M. Well I was always willing to give them the benefit of the doubt, but I feel like they kind of showed their hand with that Georgia lawmaker article and the CNN washing machine thing. And with those comments made by CNN reporters, and that ex-CIA analyst, and it ended up even Brian Stelter was calling our site fake news.

So I’m usually willing to give the benefit of the doubt, because people do misunderstand. But I just don’t think people confuse the Bee any more than they do any other satire site. And I don’t think it’s something where we at the Bee just don’t understand how to do satire right, because this sort of thing has happened forever. It’s happened for centuries: people will always misunderstand satire. I mean, the Onion has a hundred pages of fact checks on Snopes—people will misunderstand. But when that happens, it’s “look how dumb the conservatives are believing this Onion article.” And then if conservatives get confused by our site it’s like “look how easy the conservatives are to dupe.” But some liberals still think that Sarah Palin said she could see Russia from her house!

S.K. As you say, there’s no universe in which you write satire and there’s not some guy on Facebook that gets confused. You mentioned that you take some steps to minimize that—to what extent do you think you have a responsibility to do so? What are the ways you try to reduce misunderstanding?

K.M. We are careful how we structure our headlines so that they are a joke. That is the number one way. So the ones that get confused the most often are the ones where you just quote somebody. Here’s one that liberals got confused by: Trump says he’s done more for Christianity than Jesus. That was one of our pieces, and a lot of liberals picked it up and started sharing, like, “can you believe this?”

And it was structured off of something Trump actually said, that he’s “done more for the Evangelical community” than any other president. That’s how humor works: you take a real quote and you swap in something a little more crazy. The punch line is right at the end of the joke: it’s structured so you read it and it takes you by surprise. And if you click through and read the article it’s over the top, it’s obviously not real. But the problem is people just read that headline. And then they share it.

And so I think it’s more a problem of how people consume the news now than it is of bad satire. That’s something that we need people to grapple with individually, that they shouldn’t believe everything they read on the internet. It’s happened for a long time, and it’s not something we’re going to be able to fix. But it’s also not something we’re going to ruin our humor over with a big satire label. That ruins the whole setup.

But for our part, we’ve labeled our site satire a lot more prominently than the Onion even has. If you google our website, our little native tag says “your trusted source for Christian news satire.” If you google the Onion it says “America’s finest news source.” Which is fine! We even weren’t sure if we were ruining the joke by calling ourselves satire up front.

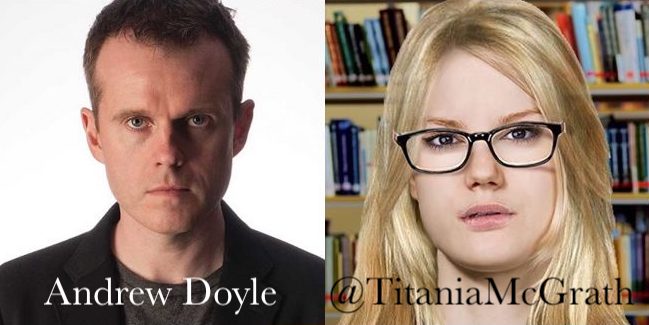

S.K. I want to go back to something you said—that satire is taking a quote that’s already ridiculous and putting in something even more ridiculous. I do often see people, who know that the Bee is satire, sharing it and saying “gosh, there’s almost no joke here.” Because the reality is so close to the joke. Or I’ll watch parody accounts on Twitter like Titania McGrath say something absurd, and the next day an actual SJW will say the same thing sincerely. So there is this sense that life is outpacing satire. Does that complicate things for you? Is it good for business, or does it make it harder to come up with good jokes?

K.M. It’s both-and. Because we have a lot of material to work with—every day I can look in the news and pull a dozen different possible things that we can write satire about, which may not have been the case ten or 20 years ago. The news cycle wasn’t that fast, things weren’t as ridiculous. But at the same time it’s a challenge for anybody writing satire, because you have to stay ahead of it. A couple of times we’ve been writing something, and we put it out there, and then people are like “oh actually this really happened.”

People will say to us “reality makes your job easy for you.” Well it kind of does, and it kind of doesn’t. Half the ideas that people submit to me, I’m like, well that’s actually true—we can’t use that! So it’s a struggle as much as it is a benefit.

S.K. You guys are playing the digital game uniquely well among satire sites. Are you thinking a lot about how to play on social media and on Twitter, as opposed to the older print model? Do you strategize about that a lot?

K.M. Definitely. It’s actually more of a bad limitation than a good one. All content now has to be shaped for social or nobody’s gonna see it. So, from how long our headlines are to what kind of image we use, to what topic we’re talking about—there are certain buzzwords we can’t use, structures we can’t use. If you write a headline trying to parody a clickbait headline, something like “You Won’t Believe What Happened Next”—if you try to do a joke based around that you’ll get five likes on Facebook because they will not show it to anybody.

So it definitely shapes our content, but I wish we were more independent from social than we are. Because, you look at something like the Onion, which managed to get famous before social, and they’re able to get away with a lot more. They’re able to get away with a little more texture, a little more depth, a little more broad content on their site. Because they’ve got almost seven million followers on Facebook. And so they can get away with only 10% of their audience seeing a joke because it’s something Facebook won’t display to them. We can’t really get away with that, because if we do too many of those jokes nobody’s visiting our site.

It’s kind of unfortunate. But we’re working on strategies to move away. We have a subscription service, where we have a lot of fans that are signing up to support us financially. We’ve built a large newsletter audience, so we’re trying to find ways to get to people directly.

S.K. Do you feel then that social media is just a total negative drain on our public discourse?

K.M. No of course it’s good, of course there’s good that comes from it. I mean, no one would know what the Babylon Bee is if it weren’t for social media. But it was a different landscape four years ago, too. I don’t know, if we launched today, if we could get any traction. It seems like new pages that launch, new sites that launch, it’s very hard to go viral. We kind of got lucky—we got in at just the right time. Adam had a little bit of a platform built with his comic that he drew, too, so he was able to kind of launch us off the ground. I think we got in just before it would have been impossible to launch the Babylon Bee.

S.K. Is that just because there’s so much competition now?

K.M. Well, that, and Facebook made a lot of changes to the newsfeed algorithm and how they handle business pages in the last few years. So now it’s pay to play—you have to buy advertising, you have to buy followers. We were kind of sneaking in right before that, so it didn’t feel at the beginning like Facebook was throttling our reach at all. But now—I believe when Seth bought the site we had around 400,000 followers, maybe a little less, and now we have 640,000 followers. And our reach is flat—it’s the same number of people that see our posts. How do you grow that much and get nothing out of it? So I just don’t know that it would be possible today to launch an enterprise like this.

S.K. It’s true that there are a lot of forces arrayed against you—it’s like a Galactic Empire’s worth of institutional power. You’ve got old world media with Snopes and CNN, and then you’ve got this Facebook contingent that gives it a digital edge. And yet it seems from talking to you like you’re fairly optimistic about the fact that people on social media have just dunked on Snopes, ignored them, made them irrelevant.

What’s your take on normal people’s capacity—the vast majority of people that read you and love you, even if they disagree—do you think they’ll be able to just get past all of this institutional antagonism from Facebook, Snopes, and so on?

K.M. All indications are that we will get around all of those hurdles. They’re more just slowdowns for us, really. And it backfires so often—it may even be a boon to us sometimes. I don’t want to oversell that case, but when Snopes attacked us last summer we saw a huge increase in subscribers, and people who were willing to go to bat for us. Same thing right now with CNN attacking us. I think people get it. And yeah, you know, the tech giants are gonna fight it as much as they can, but I think the majority really gets what we’re doing. And they’re going to find our content one way or another.

S.K. Three cheers for the Rebel Alliance then.

K.M. Yeah, exactly.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

A brief response to our favorite Quislings.

It’s hard to keep up.

Conservatives are attacking America by weaponizing our favorite things.

The popular Twitter satirist and cultural commentator talks social justice, classical liberalism, and the fate of the arts in the West.

Our “news media” tell us when to care about racial representation.