Our heroes will never be forgotten.

The Audacity of the 1776 Report

An incisive refutation of the principle of American original sin drives “professional historians” mad.

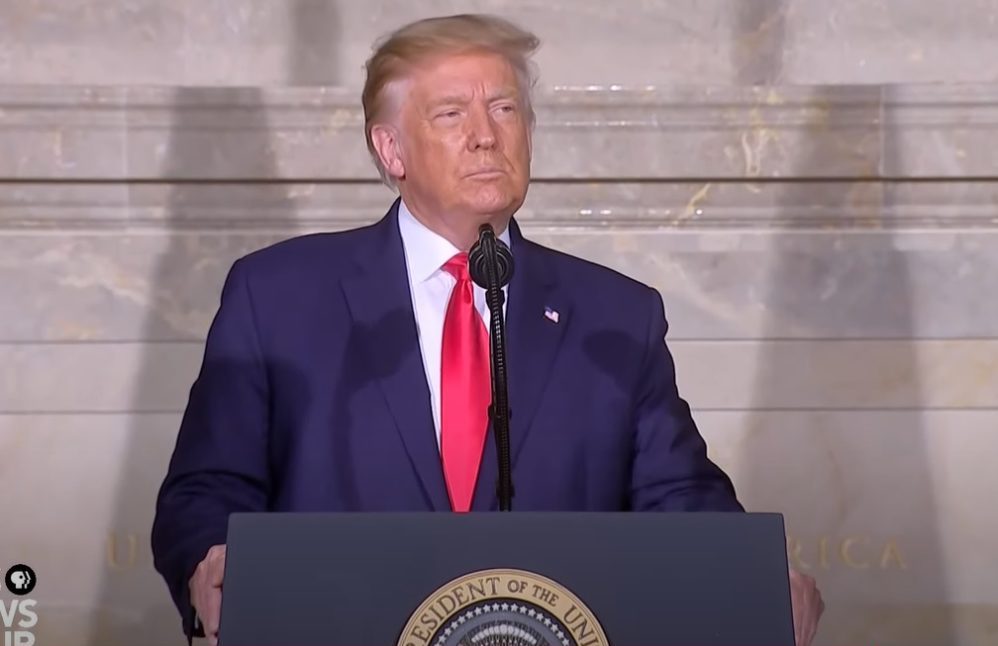

The 1776 Report, written by former-President Trump’s advisory “1776 Commission,” was released on January 18, and thus was around for only two days before being archived, with its commission scuttled. The absence of “professional historians” on the commission was a primary reason for its cancellation, according to the New York Times. “They’re using something they call history to stoke culture wars,” remarked professional historian James Grossman, director of the American Historical Association (AHA). But the arguments of the critics of the report, as well as the context of the executive order cancelling it—”Executive Order on Advancing Racial Equity”—tell a different story.

Historians are the ones who get to write history!

The AHA argued in its official “condemnation” that the 1776 Report was “not a work of history,” and seeks to undermine a “body of scholarship that has evolved over the last seven decades.” The Report includes “a full-throated assault on [intellectual corruption in] American universities,” and condemns many “contemporary social movements.” Furthermore, it “erases whole swaths of the American population—enslaved people, Indigenous communities, and women.” The critics mean that grounding the history of the nation in the thoughts, beliefs, and moral principles of its Founders, and to consider their virtues more foundational than their sins, or than the virtues of others who were oppressed or suffering, is erasure. The moral obligation of real historians, as the AHA would have it, is to tell the stories of the weak and downtrodden and see the world through their eyes.

The Washington Post catalogued the reactions of individual historians, who were apoplectic. Regarding the ahistoricity of the 1776 Report, author Alexis Coe sputters, “I don’t know where to begin.” For instance, while the Report says that George Washington freed all the slaves in his family estate “by the end of his life,” in fact, Coe points out, he only left direction for the slaves to be freed after the death of his wife. University of California at Davis historian Erich Rauchway excuses his incapacity to express his shock about the Report, explaining “I may sound a little incoherent when trying to speak of this, because the report itself is not coherent.” His key claim about the inaccuracy of the 1776 Report is its failure to acknowledge that modern “group rights” are anticipated by the founding principle of federalism, and thus not antithetical to the Declaration’s foundation of rights in individual liberty, as the report insists. But this insistence is absurd. It is axiomatic that group rights override individual rights, while federalism supports them.

Complaints about shoddy scholarship and the lack of input from professional historians are disingenuous. Are we to believe that “Boston University historian Ibram X. Kendi” would reject a commission report that found that Americans have been and continue to be racist because it didn’t include footnotes? No, he hates the 1776 Report because it makes a mockery of his supposed expertise. Or that the author of A Black Women’s History of the United States was most upset by the fact that the 1776 Commission counts no History department faculty among its members? No, she hates it because it doesn’t talk about the “harmful impacts of settler-colonialism” or “the plight of queer people.” Critics of the 1776 Report offer nothing in the way of substantive analysis. They rejected the report because it contradicts their favored narratives and pet topics.

What are you doing with my narrative?

A predictable critique along these lines is that the Report tells a story which diminishes the importance of slavery in American history. Where it does address slavery and racial oppression, it distorts them by absolving the founding generation of its guilt or by illegitimately appropriating the statements of black civil rights leaders in defense of the principles of the American founding.

Indeed, there is no mention of slavery in the report until the bottom of the tenth page, and then, the report is unapologetic, stating that the charge that the founders were hypocrites is a “lie,” averring that the “American Revolution… marked a dramatic sea change in moral sensibilities” which “planted the seeds of the death of slavery in America,” and that in a “genuine civics education,” students would “learn the reasons America’s founders gave for building our country as they did,” recognizing “the American story’s uglier parts,” but with the understanding that there are “unchanging principles that transcend history,” and that our founders struggled to apply these principles to the circumstances they were given.

The response to these assertions has been outrage rather than refutation. It is undeniable, for instance, that “we learn from the founders’ public statements and private letters that they condemned [slavery],” because this is factually true. They cannot refute the claim that while Frederick Douglass, and later Martin Luther King, Jr. often quoted approvingly from the Declaration and Constitution, the later civil rights movement “reframed debates about equality in terms of racial and sexual identities,” because this is evident not only in the historical record, but is obvious to every American today. The critics’ only response is to lie or to stammer.

I feel so uncomfortable right now.

David Blight is a professional historian at Yale, where he directs the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. On January 20 he was delighted by the inauguration of the new president, tweeting, “A day for tears but also firmness, the straight back, and the brilliance of Vice-President Harris.” A few days earlier, he was less elated, attacking the 1776 Report: “Beliefs devoid of history. I feel so uncomfortable even bringing attention to this mess.” Yet, in a series of scathing, vituperative tweets—”puerile, politically reactionary document”; “fascist and authoritarian propaganda”; “viciously right wing, willfully ignorant”; “the final desperate act of MAGA functionaries”—he offers not one substantive critique of the Report that would satisfy an undergraduate writing assignment. In a Politico interview Blight spat out, “my reaction is anger. It’s disgust.”

But his revulsion is provoked by the purpose of the 1776 Report, not its contentions or facts. The notion that history ought to be patriotic, that we ought to learn from our founding rather than hollow it out is anathema to Blight. “So many of us have spent our lives trying to turn that around,” he explains. “For three or four generations, we have been rewriting the history of the United States.” How dare non-historians object to this revolutionary project?

What swamp did you crawl out of?

Contrary to the insinuations of the critics, the authors of the report are hardly laymen, amateurs, or activists. Critics point out that Larry Arnn, who headed the 1776 Commission, is the president of “conservative” Hillsdale College—as if the political leanings of the place discredit any intellectual associated with it—without, of course, applying the same standard to themselves. Arnn has a doctorate in government, and studied history at the doctoral level in England, where he worked as lead researcher for Martin Gilbert, the official biographer of Winston Churchill. Charles Kesler, another member of the commission, has a Ph.D. in government from Harvard. Victor Davis Hanson is a Stanford educated classicist and renowned military historian. Thomas Lindsay, whose political science doctorate was awarded by the University of Chicago, was president of Shimer College.

Arnn, Kesler, Hanson, Lindsay, and others on the Commission are at least as qualified as “professional historians” to write a report about the principles of the founding. In fact, with their broad educations and understanding of American history in light of developments in American political theory and government, not to mention the connection of American civilization to our Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian intellectual and moral heritage, they are actually much more so. But the point is not which group of scholars to trust, but that we need not and ought not rely on university-trained “experts” for something as important for our self-government as a narrative of our nation’s history.

However, in “The Ideas Behind Trump’s 1776 Commission Report,” The New York Times’ Jennifer Schuessler attempts to show that the report was informed by extreme and partisan views. David Blight attempts, lamely, to make the Commission members seem like Confederate sympathizers, baselessly connecting the Report to “Lost Cause” dead-enders and hearing “echoes” of Thomas DiLorenzo and Charles Adams, who have written “books that hated Lincoln.” But no one is mentioned in the 1776 Report more than Lincoln, and always with the highest esteem.

Schuessler is correct to recognize the influence of the Claremont Institute in the Report’s description of “the so-called administrative state.” So is Joshua Tait in his contribution at The Bulwark. Tait, a professional historian, studies American conservatism, particularly “conservative efforts to construct historical narratives about the American past.” And this research has often included the “West Coast Straussianism” of Harry Jaffa and his students, whose mark is all over this report. So he doesn’t make the embarrassing mistakes others do. Tait writes, “In short, the 1776 Report is simplified West Coast Straussianism with the presidential seal slapped on it.”

The epithet “West Coast Straussian” implies that the 1776 Report is a bizarre, schismatic product of an obscure academic sect. Tait, both here and generally, situates American conservatism not as a repository of ideas to be taken seriously in their own right, perhaps even representing mainstream American opinion, but as a curious and dangerous phenomenon. That this scholarship recovers and produces much that is valuable (he often shares interesting snippets of his research on Twitter) does not change the fact that it is implicitly an argument from power: we are strong and many; you are few and weak. We, not you, get to say what is important in American history. The audacity of the 1776 Report is to contest this.

Why We Need 1776

The greatest virtue of the report, which its critics take to be a vice, is that its basic orientation to American history is healthy and normal. It has this in common with the American citizen, but not at all with the academy. This disjunction between elite academic sentiment, which holds the American people in contempt for their positive regard for the history of their own country, and the feelings of those people, is felt every day by normal American families facing insipid and divisive curricula in their children’s schools. They increasingly have the sense that there is a war on, and they are the targets.

Historians used to understand that they had a civic responsibility to tell a story that, while saying nothing false, served an epideictic and exhortative function, encouraging citizens to emulation of their ancestors’ virtue. Cicero gave the task of teaching history to the orator, which is to say that he understood not only that history serves a public function, but that it is a kind of persuasion about the just, the advantageous, and the noble. At the very least, the historian ought not to harm the public. At his best, he ought to inspire it with a sense of its greatness, as Livy did for the Romans.

Critics of the 1776 Report charge it with being childish and simplistic. David Blight said, “It’s like some kind of sixth-grade history from the 1950s.” He means this in a bad way. It’s worth, asking, though, what a grade-school history ought to look like, and what should be included, and what not. In what spirit ought we first to approach American history? What is the first story you learn, before you learn the nuances and complexities, before you can have an informed, enlightened patriotism? If the first story you learn is that America is a nation founded for white male slaveowners and on that principle (a profound lie), then no amount of subsequent nuance will blossom into an intelligent love of country.

What the 1776 Report shares with the average American is the instinct that no matter our race, sex, or origin, piety and gratitude ought to be our initial orientation to the history and principles of our own country. Its audacity is to carry that spirit through to an academic study of American history and principles, and to bring it back down again to a grateful people.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Could it be that the “Aristotelian” teaching of teleology is exoteric?

Self-criticism, Progressivism, and post-modernism.