Between the abyss and what goes on in Portland and the Magnificent Mile, there is for the moment nothing else but Trump standing in the breach.

The American Economy’s Wile E. Coyote Moment

The bottom falls out of a years-long spending binge.

The graphs in this article are the author’s own, using data from Bloomberg.

Call it America’s Wile E. Coyote moment.

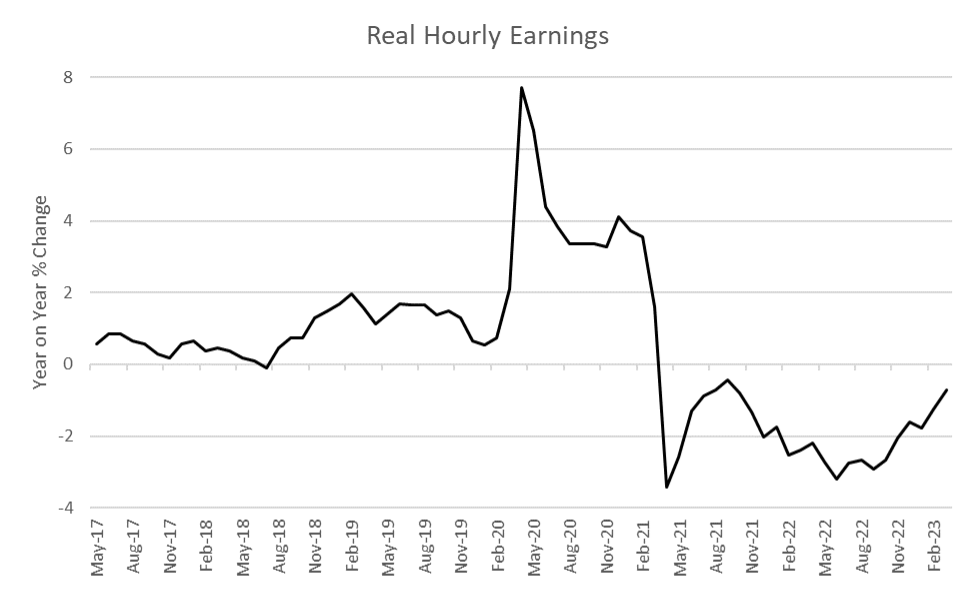

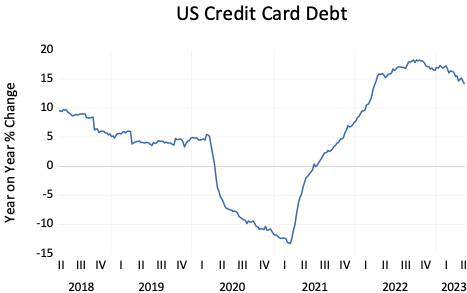

The end of the $6 trillion COVID stimulus and the erosion of real earnings by inflation might have put the economy into recession already, but U.S. consumers continue to buy with plastic to make up for lost real earnings. Result: we continue treading air even as the bottom sags beneath us.

The U.S. economy continues to show modest growth, with real GDP rising at a 1.1% annual rate in the first quarter, largely due to higher consumption, despite falling real hourly earnings.

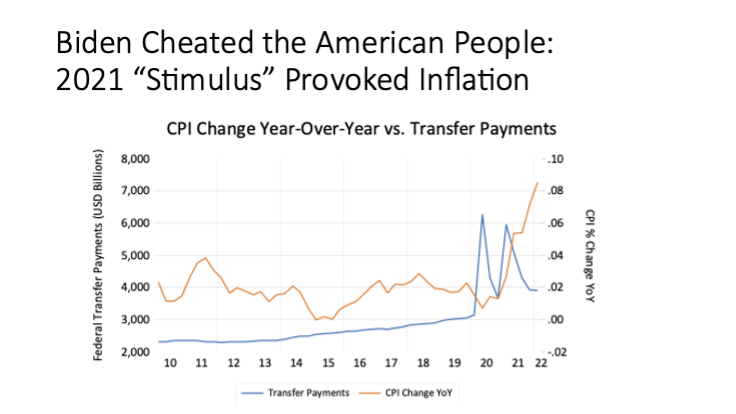

Biden unleashed supply-side inflation by helicoptering $3 trillion into an economy already in recovery after the COVID shutdown. One can debate the wisdom of the Trump Administration’s earlier $3 trillion stimulus, but that was a shot of adrenalin for a patient with heart failure. Biden doubled the dose and unleashed an inflation driven by demand for goods that the U.S. economy couldn’t produce fast enough.

The problem was spending, not easy money (unlike the 1970s, when easy credit fed an asset price bubble, credit growth was subdued going into the inflationary surge of 2021, as I documented in a 2022 study for RealClearPolitics). The Fed first claimed there was no inflation, and then claimed it was transitory, and finally decided that the right response was to tighten credit—even though credit didn’t cause the problem in the first place.

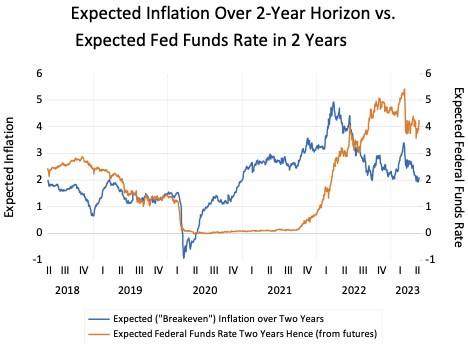

The chart above shows a market-based measure of inflation expectations, namely the difference between the payout of two-year Treasury notes indexed to inflation and the yield on ordinary Treasury notes. If the inflation rate matches the market’s bet, investors in inflation-indexed Treasuries break even. This so-called breakeven inflation rate over two years soared from zero to 4% before the Fed started tightening. Now it’s back down to 2%, but the Fed is still tightening.

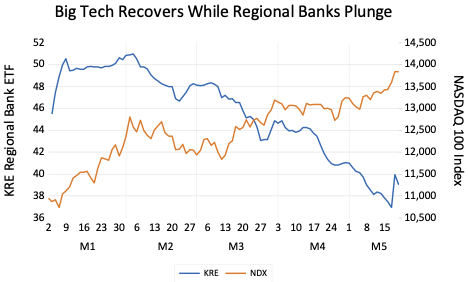

When the Fed jacked up interest rates, the value of the $1.6 trillion in Treasury securities that banks had purchased to help finance the COVID stimulus plunged. That squeezed Silicon Valley Bank and other regional banks, triggering an April run that bankrupted a couple of major regional banks and left others on life support. Regional bank stocks plunged. At the same time, Big Tech stocks surged. In a credit crunch, the players with the most cash come out ahead.

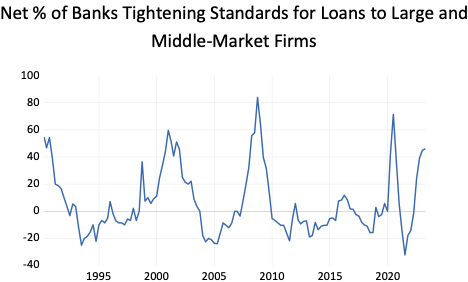

The result is a credit crunch for American small- and medium-sized business, and probably an actual recession rather than barely noticeable GDP growth.

Banks are tightening loan standards for small- and medium-sized firms, to an extent we have only seen during the 2020 COVID crash, the 2008 financial crisis, and the recession of the early 2000s.

There is a global dimension to the credit crunch as well. European and Japanese banks owe roughly $14 trillion to U.S. banks, for loans they took out to hedge their dollar assets. America’s chronic current account deficits of the past 30 years amount to an exchange of goods for paper: America buys more goods than it sells, and sells assets (stocks, bonds, real estate, and so on) to foreigners to make up the difference.

America now owes a net $16 trillion to foreigners, roughly equal to the cumulative sum of these deficits over 30 years. Foreigners who own U.S. assets receive cash flows in dollars but want to convert these into their own currencies. If you own an American bond paying a coupon in dollars, and you want to convert that cash flow into Euros, for example, you sell the dollar short: You borrow dollars and sell them for Euro. But someone must lend you those dollars to sell short. That’s why European banks have enormous borrowings from U.S. banks.

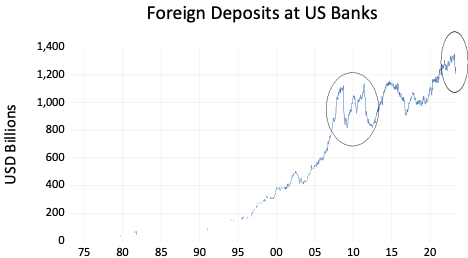

On a couple of past occasions, the business of hedging the currency risk of foreign holdings of U.S. securities broke down. A rough and ready indicator of trouble in international lending markets is the volume of foreign banks’ deposits with U.S. banks, which moves in the same direction as U.S. banks’ international lending.

There was a sharp pullback in foreign deposits at U.S. banks during the 2008-2009 global crash, and again during the European financial crisis of 2011.

After the April run against U.S. regional banks as well as Credit Suisse, foreign deposits at U.S. banks began to drop sharply. That isn’t a global bank crisis like 2008, nor even a regional bank crisis like 2011. But it is a global squeeze on dollar credit, in parallel to the credit crunch in the United States.

What it means is that a great deal more trade will be financed in Chinese RMB, Indian Rupees, Russian rubles, and other rivals to the dollar, further shrinking America’s economic footprint and increasing our vulnerability to future crises. Who can say when those will come—but they always do, and when they do it pays to be ready. We are not.

We cannot continue running up massive budget deficits and trade deficits. The crunch could come as early as the beginning of June, if Congress refuses to give the Biden Administration authority to continue buying votes with reckless spending. Or the present malaise could persist for years, until America’s creditors at last treat us like Britain in the 1960s or Italy in the 2010s.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The app-based "Dragnet" that Sgt. Friday never dreamed of.

The “Great Reset” is still chugging along.

The pandemic inverted the normal meaning of generational sacrifice.

Biden’s spending spree and Fed blunders started the bank crisis.

We must root out dishonest Border Patrol Agents.