What may finally get us is probably not what we expect.

Telos of Misery

Unadulterated liberalism is creating a nation of unhappy scolds.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics recently published a multifaceted survey that measures the self-reported happiness of its respondents. Receiving data from across the employment spectrum, the survey sought to quantify the types of jobs and habits that contribute to a well-lived life. The image that emerges pays homage to the benefits of old-fashioned virtue. According to the survey, quality of work and time spent outdoors are among the most significant indicators for self-reported happiness. These are followed up by church participation, exercise and recreation, and various community related voluntary activity.

Against the lived experience of happy people, the creeds of today’s progressives, who have progressed right past their own former liberalism, seem patently absurd—as if manufactured to renounce the very conditions of happiness. In its multitudinous iterations, we can observe the deconstruction of the conditions for happiness. This dynamic is clearly at play in an environmental movement that seeks to sever man from the work of his hands—particularly those nasty lumberjacks whose happiness, according to the BLS, is among the highest of any trade. We can also observe this hatred for the good in a neo-Malthusian movement that resolutely coordinates the deprivation of family formation while calling it “reproductive justice.” Those unflappable anti-art extremists who made headlines last year for desecrating Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” with soup would righteously deprive the unwashed masses of whatever emanates beauty. And lest we forget, my personal favorite, a body positivity movement that fit shames in the name of fat equity. In each of these cases, the overriding liberal habitus seems assertively ordered toward maximizing human misery.

How has this come to be? The liberalism of the nineties may have had its rough edges, but at least it seemed invested in maximizing happiness. But what kind? In his book Wanting, economics professor Luke Burgis may have given us an answer. Following the Jesuit priest and academic Robert Spitzer’s four levels of happiness—physical/material, ego-comparative, contributive, and transcendent—Burgis formulates a theory of two distinct engines for manifesting happiness. The first of these occupy the base level conditions for its realization—think of sating the appetite and scoring points for the ego—and they are what Burgis defines as “thin desires.” They are fleeting and prone to rivalry. The more robust form, called “thick desire,” is ordered toward the lasting goods of family, faith, and meaningful work.

Thin desires bubble up from the bottom of Spitzer’s happiness hierarchy. They are consumed with pleasure for its own sake. Consider the young man swiping through his Tinder app for the next conquest. So long as he is entrenched in the feedback loop of hookup culture then transcendence, as much as he can experience it, is purely horizontal and immanent. Ordered toward consumption, thin desires are fleeting, dangerously prone to rivalry, and unable to manifest any lasting satisfaction.

Now consider a gentleman who is also in the market for the fairer sex but his desires are “thick” and ordered toward marriage and family. These goods can be found at the top of Spitzer’s hierarchy; they require self-giving and set the stage to achieve a form of vertical transcendence. By training his appetites, eschewing those self-satisfying horizontal interests as telos, the young man has already done much of the hard work of being happy.

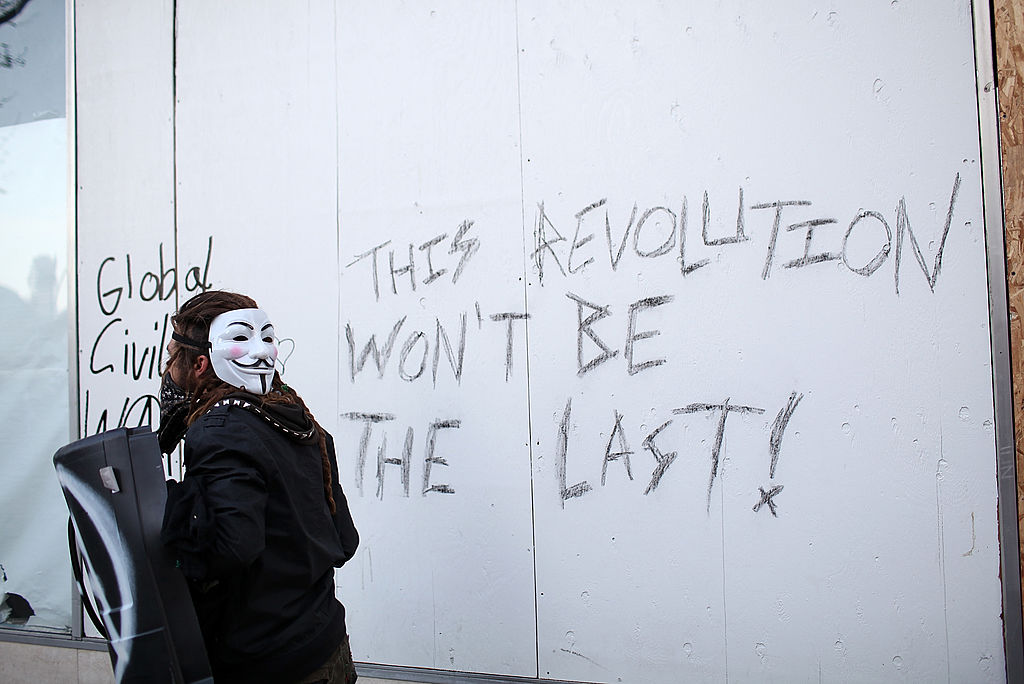

Liberal anthropology, as much as it can be observed as such, morphed into a progressive teleology of thin desire after thin desire. Transcendence, in the paradigm of the thin, can be achieved but purely on a material and self-affirming plain. Consider again those Left activists relentlessly manufacturing the conditions to maximize human misery. Their endeavors almost certainly have an emotional payout. Smug self-righteousness, identifying with the mob, undermining established norms, and ultimately cathartic release all offer the brain a flood of dopamine. However, by their nature, these experiences are incredibly fleeting and necessary to reenact ad infinitum to be maintained. These behaviors all suggest some striking consistencies with the machinations of a primitive mind. In ancient societies, resources are dangerously finite, goods are often zero sum, and peer-to-peer violence is practically inevitable. In fact, for the primitive, religion is the social technology that keeps a lid on the potential for violent outbursts often roused by thin desires.

Consider once again the BLS survey in this context. The good life is one being lived by people who undertake meaningful work and are active within their communities and regulars at their local liturgies, because these are where individuals ordered toward thick desires move toward their fulfillment. They are almost certainly married and the heads of families, as Marc Barnes of New Polity poetically demonstrates in a recent essay “Marriage is the Form of Christian Politics”: “Marriage leaps for virtue like a man leaping for a moving train.”

This may well explain the super-abundance on the Left of angry women who appear to loathe marriage and the family. Shorn of the benefits of primeval religion and stricken with the logical results of thin desire, the activist culture they embody is a powder keg of rivalry, mob dynamics, performative outrage, and scapegoating. It will run the gamut of human experience, with one clear exception—an absolute lack of any state of being resembling deep fulfillment. For the teleology of the progressive Left, to be happy is to be in the need of blood sacrifice. It is the ontological incarnation of thin desire.

In the bifurcated, postmodern mind this is anathema—but then again, as the survey demonstrates, it is also science. The takeaway, obviously, is grandma’s axiom that “misery loves company.” In publishing this survey, the Post has brought to light certain implications. The most important of these may very well be the insurmountable gap between conservative and liberal political interests. One group will obsessively froth at the mouth to deprive their peers of the one human experience beyond their reach and the other labors away in pursuit of that increasingly dwindling joy.

These are the choices at hand: One is the gnostic unreality, a path of pagan power worship, Malthusian anti-humanism, appetitive exploitation, and near-guaranteed misery. The other is ordered toward the joy of a well lived life. One orients toward thick desires that manifest true happiness while the other wallows in masturbatory self-indulgence.

The Washington Post may have offered a significant mea culpa to the American experiment. Man is destined for an incarnational existence, but the overriding question is whether his desire will be rooted in the thick or thin? Which way will it be, American man?

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Some friendly liberal advice to Republicans.

Progressives do not want the same things as most Americans.

Turning basic facts into thought crimes turns normal people into thought criminals.

Conservatives are attacking America by weaponizing our favorite things.