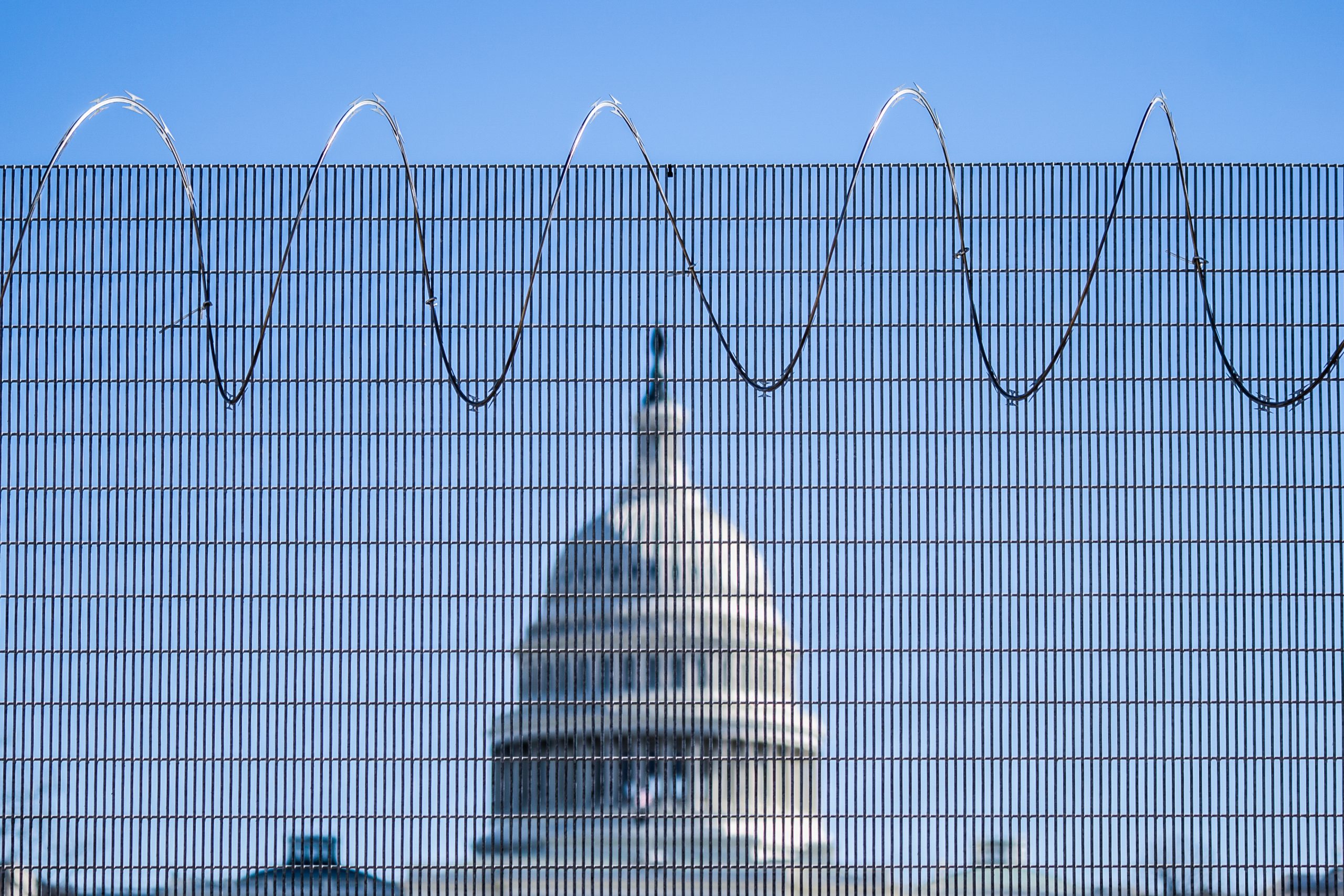

The Biden Administration is using concerns about terrorism to crush Trump and supporters.

Taking Aim at the First Amendment

Jack Smith’s January 6 indictment of Donald Trump is part of Biden’s whole-of-government effort to end free speech.

Last week’s federal indictment of Donald Trump is a watershed moment in the politicization and weaponization of the Department of Justice. The DOJ is doing that which it accuses President Trump of doing—attempting to change the election and deprive Americans of their right to vote by advancing extreme legal theories. Against the free passes the Obama-Biden DOJ gave the Biden family, Hillary Clinton, Lois Lerner, thousands of rioters after George Floyd’s death, and protestors at the homes of Supreme Court justices, the rupture is complete. This is not the America for which millions of our citizens fought a war of independence, the Civil War, and two world wars.

As unprecedented as this indictment might be in its attempt to criminalize political speech, at its core it is a continuation of the Biden Administration’s massive whole-of-government effort to suppress views with which it disagrees (see here and here). The DOJ tested the waters for criminalizing free speech by investigating parents who spoke out at school board meetings. This indictment is the nadir of the slippery slope down which the administration has descended. Rather than merely demonetize or deplatform dissenting views, the indictment seeks to interfere in the 2024 election and imprison the speaker.

No administration has come close to this outrage since 1807, when, on flimsy evidence, President Thomas Jefferson unsuccessfully prosecuted his own former vice president, Aaron Burr, for conspiring to seize the Louisiana Purchase and parts of Texas. By contrast, when Trump became President he rejected calls to prosecute Hillary Clinton, despite his supporters’ chants to “lock her up.”

The indictment should not be evaluated for whether it accurately recounts what Trump said, no matter how distasteful that may be for many, or whether he created circumstances that led to the events at the Capitol on January 6, no matter how loathsome that may be for most. Rather, the indictment must be evaluated for its cynical, hypocritical, and dangerous attack on the First Amendment, and for weaponizing the DOJ against President Biden’s political rival. It was timed so that a trial might occur in the run up to the 2024 election, and was announced the day after Devon Archer’s testimony exposed Joe Biden’s lies to knock that testimony from the news cycle.

The indictment is a whiny, indignant recitation of Trump tweets and statements that annoy special counsel Jack Smith and the Left. Even Smith admits, “the Defendant had a right, like every American, to speak publicly about the election and even to claim, falsely, that there had been outcome-determinative fraud during the election and that he had won.” He further acknowledges that Trump also was “entitled to formally challenge the results of the election,” though he limits Trump to actions that are both “lawful,” and in the view of the DOJ, “appropriate.”

For most of its 45 pages, the indictment’s rationale is little different from the arguments the Government recently advanced in its opposition to plaintiffs’ successful request for an injunction in Missouri v. Biden, which sought to stop the administration from pressuring social media companies to suppress protected free speech. In that action, now on appeal to the Fifth Circuit, the government claimed it had the right and duty to suppress falsehoods, and “malinformation,” which the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency defines as “based on fact, but used out of context to mislead, harm, or manipulate.” In other words, facts that aren’t swaddled in leftist “context” must be subject to government control.

Here, the indictment accuses the President of tweeting or asserting falsehoods, as judged by sources Smith finds credible, or of adopting novel legal theories advanced by renowned lawyers with whom Smith disagrees, for the purpose of influencing the vice president, DOJ, and elected officials to proceed as Trump advocated. The indictment reveals Smith’s bias by mischaracterizing two Trump’s tweets that are irrelevant to the alleged crimes. The first called for the rioters to “Stay peaceful!” and the other for them to “remain peaceful.” The indictment alleges that Trump was “falsely suggest[ing] that the crowd at the Capitol was being peaceful.”

As the Supreme Court explained in West Virgina State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), protecting political speech is part of the “fixed star in our constitutional constellation.” The First Amendment even protects false political speech, United States v. Alvarez (2012), and advocating the commission of a crime or violence to advance political goals, unless the speech is a direct incitement to imminent lawless action, Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969). The indictment fails to allege why Trump’s speech goes beyond the protections of the First Amendment, or why it constitutes a crime.

The indictment alleges that Trump engaged in a conspiracy for the purpose of “overturn[ing] the legitimate results of the 2020 presidential election by using knowingly false claims of election fraud to obstruct the federal government function by which those results are collected, counted, and certified.” Trump allegedly “spread lies that…he had actually won. These claims were false, and the Defendant knew that they were false. But the Defendant repeated and widely disseminated them anyway—to make his knowingly false claims appear legitimate, create an intense national atmosphere of mistrust and anger, and erode public faith in the administration of the election.”

The indictment also alleges that the legal theories developed by Trump’s lawyers John Eastman, Kenneth Chesebro, Rudy Guliani, and Sidney Powell, and by DOJ official Jeffrey Clark, were wrong and that it is a criminal offense for lawyers to advance untested or novel theories; that because numerous Trump advisors and supporters told Trump that the fraud he alleged had not occurred, Trump was required to believe them and not those who disagreed, or rely on his own analysis of the situation; and that because Trump repeatedly tweeted, lobbied the vice president, members of Congress, and DOJ officials to accept his view of the facts and his lawyers’ view of the law, Trump overstepped his free speech rights.

The indictment seeks to criminalize the right of lawyers to provide frank legal advice, free speech, and other activities never intended to be covered by the statutes it cites by accusing Trump of four crimes: conspiracy to defraud the United States; conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding; obstruction of, and attempt to obstruct, an official proceeding; and conspiracy against rights. These allegations are an invitation for Trump to re-litigate his election fraud theories.

The first count under 18 U.S. Code § 371 fails because the Supreme Court has consistently limited the crime of fraud on the United States to financial crimes. See for example, McNally v. United States (1987), Ciminelli v. United States (2002) and Percoco v. United States (2003).

The statute on which the indictment relies for its second and third counts, 18 U.S. Code § 1512, is meant to criminalize witness intimidation, not puffery or bluster intended to persuade—or even browbeat—vice presidents, DOJ officials, or members of Congress. Even if Section 1512 applied to Trump’s swagger, the government must prove that Trump acted with “corrupt” intent. To do so, most legal experts agree the government must prove that Trump knew he was lying, though some circuits accept other means of proving corrupt intent. It is unlikely that the Supreme Court, which has rejected efforts to broaden similar statutes, would allow the government to establish guilt without proving consciousness of wrongdoing. In 2018, the Court declined to grant certiorari to resolve this issue.

The last count is based on 18 U.S. Code § 241, which was passed after the Civil War to stop the Ku Klux Klan from intimidating freed slaves from voting. Though the Supreme Court sustained a conviction for ballot stuffing in Anderson v. United States (1974), most legal experts see that case as an outlier. It is unlikely the Court would sustain a conviction that does not include violence or the threat of violence, or that is based on filing lawsuits and petitioning the most powerful elected officials in the nation.

Further, because Trump’s actions occurred while he was president and pertained to the electoral process, he may have immunity. In Nixon v. Fitzgerald (1982), the Supreme Court held that President Richard Nixon was entitled to “absolute immunity from damages liability predicated on his official acts.” Nixon was a civil case, but the analysis may apply here, as well.

The indictment alleges two acts, as contrasted to mere speech:

- The creation of fraudulent elector slates in seven contested states. The indictment acknowledges that the vice president and Congress refused to consider the alternative slates. Though federal fraud statutes do not generally require that an official act in reliance on the fraud, they do require that there actually be a fraud, viz., that the official does not know the truth. It is improbable that any relevant U.S. official was confused by the charade. Though this allegation appears weak, it is the only material allegation in the indictment that goes beyond the effort to criminalize political speech, and it might be provable. But, as has been true for 215 years and most recently for so many potential prosecutions of Democrat politicians, prosecutorial discretion should have been exercised to decline prosecution of this farce.

- Trump verified a court filing after he was made aware that “some” of the allegations and evidence proffered by experts in the filing were inaccurate. It is unclear if the verification certified the accuracy of the experts’ contributions, or only that the contributions came from the experts. Regardless, verifications of incorrect information in civil actions are common, seldom prosecuted, and when prosecuted, are usually misdemeanors.

The unprecedented sweep of Smith’s theories is emphasized by an abbreviated list of those to whom it would apply if carried out in a non-partisan judicial proceeding observing the same degree of scrupulousness as Smith demands:

- Jack Smith, whose aggressive prosecution of Virgina’s Republican governor Bob McDonnell based on an unprecedented re-definition of federal bribery statutes was overturned unanimously by the Supreme Court in 2016. Smith’s extreme, false legal theories destroyed McDonnell’s political career and deprived Virginians of the right to vote for him.

- The FBI created the misimpression that the Hunter Biden laptop it seized in 2019 had not been vetted, and in a coordinated disinformation campaign organized by Biden campaign advisors, 51 former high ranking intelligence officials referred to the laptop as having “the classic earmarks of a Russian information operation.” Collaborating with, and coercing, social media, they blocked distribution of the New York Post’s reporting about the laptop until after the 2018 election. Polls show that truthful coverage of the laptop story before the election likely would have changed the outcome (see here and here).

- The Hillary Clinton campaign and its law firm Perkins Coie devised a plan to manufacture a false dossier that painted Trump as a Russian asset, elected through unlawful Russian interference in the 2016 election. Working with like-minded journalists, Democrat leaders, and senior FBI agents and attorneys, the campaign obstructed official functions, and created an intense national atmosphere of mistrust and anger that eroded public faith in the administration of the election.

- Since her loss in the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton and other Democrat leaders have repeatedly asserted that she was the rightful winner. Clinton said, “you can run the best campaign, you can even become the nominee, and you can have the election stolen from you.”

- House Democrats have objected to certification of Republican electors when Republicans won the presidency in 2001, 2005, and 2017. Democratic Congressman Bennie Thompson, who lead the January 6 Committee, voted against certification of the 2004 presidential election and refused to attend President Trump’s inauguration, claiming Trump was not a “legitimate” president. Democratic Congressman Jamie Raskin, who is also a leading figure on the committee, did the same and voted against the certification of the 2016 presidential election. Vice President Kamala Harris has repeatedly claimed Trump is an illegitimate president.

- In 2000, Al Gore asserted novel legal theories to challenge the presidential election in Florida. Concurrently, the Florida supreme court ignored applicable law to favor Gore’s candidacy. But for the U.S. Supreme Court, voters would have been deprived of their votes for George Bush.

The Biden Administration, DOJ, and the Left are committed to suppressing political speech and canceling those, particularly Donald Trump, who pose a threat to the global order they champion. Starting with the First Amendment, the Bill of Rights is the foundation of our freedom, including the almost unbridled right of free speech and the right to petition government for redress. The right to counsel is embedded in the Sixth Amendment and its sanctity has been part of our system from the start.

This indictment, and the Biden Administration’s massive social media censorship effort are part of the same malignancy that is destroying free speech, and the rights of people of all political perspectives to advocate their positions without fear of retribution.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The Left's Jan. 6 tactics are nothing new.

The indictments of Donald Trump represent a power play, not the interests of justice.