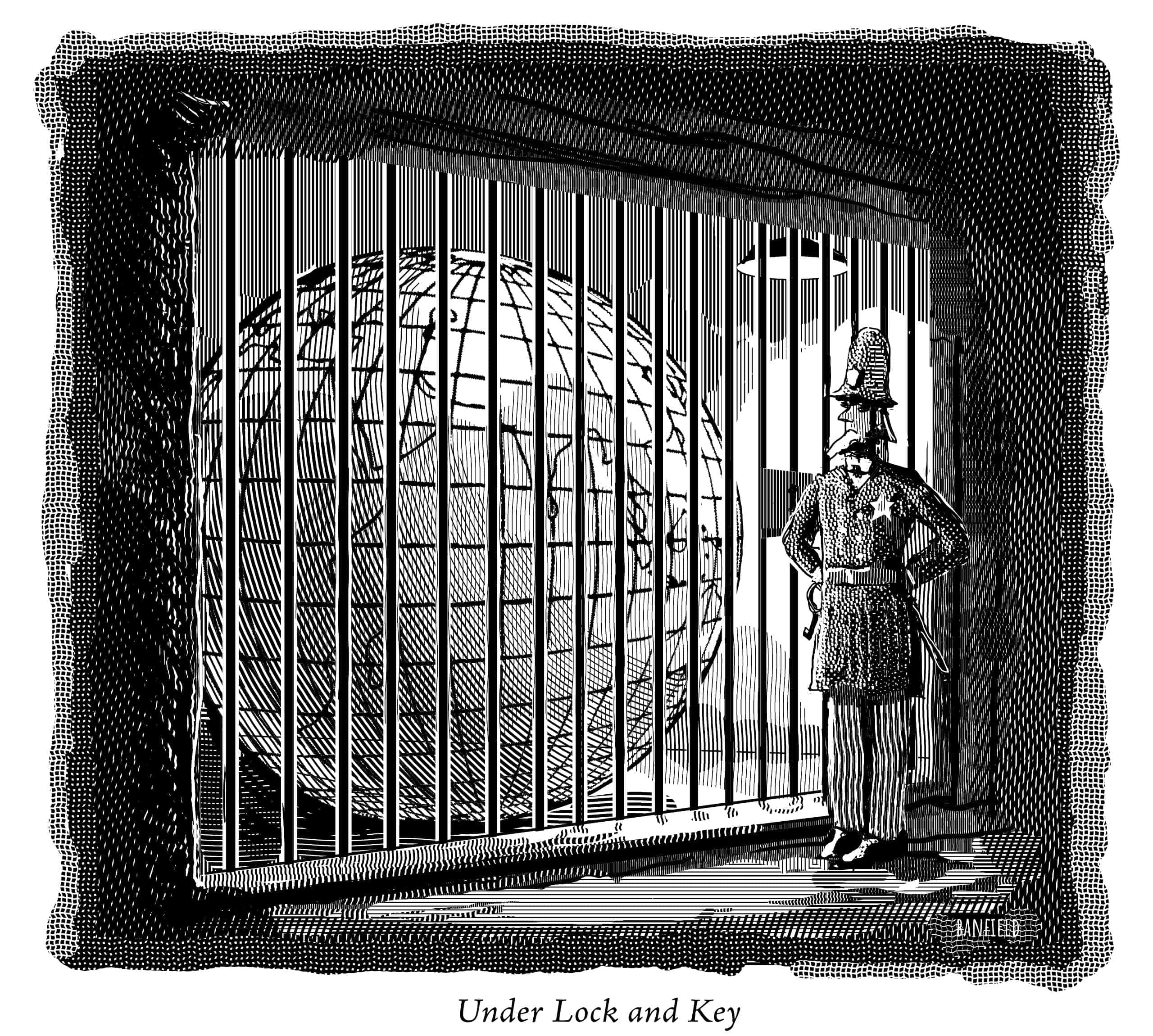

Though government weaponization is real, that doesn’t mean we don’t face external threats.

Securing the Nation

Without a positive vision of the nation, there is no national security.

What follows is an excerpt from Julius Krein’s essay, “Securing the Nation,” from the 25th anniversary Fall 2025–Winter 2026 issue of the Claremont Review of Books.

Today, the concept of “national security” is a staple of our political vocabulary, common in everyday language and entrenched in official institutions such as the National Security Council. But it was not always thus. Total Defense by Andrew Preston, a Canadian who is now a history professor at the University of Virginia after nearly 20 years on the faculty of Cambridge University, traces the rise of this concept and how it displaced earlier notions of national defense during the course of the 20th century. It is an important history, and one with underappreciated implications.

The book’s subtitle—The New Deal and the Invention of National Security—distills its thesis: the concept of national security as we know it today (involving military and foreign policy matters not limited to territorial defense) coalesced during the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt. Before the New Deal era, “national security” was used relatively rarely, and often to refer to something more like economic and political stability or, in the 19th century, national unity versus sectional interests. But in the 20th century, a new vocabulary was required to grapple with increasingly grave foreign threats that did not involve the imminent invasion of U.S. territory. Such a vocabulary was largely lacking in World War I, but the term “national security” emerged in the years leading up to World War II.

Preston’s sometimes exaggerated language can occasionally suggest that this era’s national security policy was driven mainly by the New Deal’s internal logic, amounting to little more than another New Deal program. He describes the 1947 National Security Act (which created America’s modern security architecture including the Department of Defense, Joint Chiefs of Staff, and CIA), for example, as “a New Deal for the world.” A more modest and probably more accurate reading, however, is simply that both Roosevelt’s national security policies and New Deal economic policies responded to similar developments, technological and social, and shared certain approaches and methodologies, such as frameworks of risk management and collective insurance as well as a high-modernist confidence in technocratic planning. On this point, the book is convincing. The policy framework for dealing with the world beyond America’s borders was “national security,” a counterpart to the overarching domestic policy objective, “social security.”

***

Preston is also adept at tracing subtle rhetorical shifts and locating their sources across a variety of policy domains and social currents. He shows, for instance, how Roosevelt’s national security rationale for the United Nations succeeded where Woodrow Wilson’s global-humanitarian arguments for the League of Nations had previously failed. The book makes a compelling case that the “invention” of national security shaped the strategies of the time and continues to influence policy today, often to our disadvantage. In pursuing “national security” we are, without knowing it, still viewing the world through a 1930s lens.

Unfortunately, Preston is often so attuned to the subjective experiences of the historical actors he portrays that he can lose sight of the objective conditions in which they operated. Indeed, he doesn’t really attempt to analyze the latter outside of his protagonists’ own statements and perceptions. Total Defense is the rare academic book that could benefit from additional factual detail and more theoretical context. Without any larger perspective to ground his analysis, Preston gets caught in some of the same confusions as his subjects. And while the historical material he surfaces is rich, the lessons he draws from it may not be the right ones.

***

America has always enjoyed a uniquely advantageous geographic position. As the overwhelming hegemon of its hemisphere, it has faced little risk of foreign invasion since the War of 1812. Until World War II, the United States was able to spend much less on its military than European and Asian powers, while still expanding across the continent. The greatest security risks throughout this period were internal, mainly the sectional divisions that culminated in the Civil War. Later, Preston observes, the United States also had to contend with large immigrant populations. Although the threat from treasonous “fifth columns” was minimal and often exaggerated, these diasporas occasionally sought to push the United States to intervene in old-world conflicts and invited foreign interference in U.S. policy, a problem that continues to the present. Nevertheless, for much of its history, America had little reason to concern itself with security matters beyond its territorial defense, which was not an especially difficult task.

Around the turn of the 20th century, however, industrialization began to disrupt these favorable assumptions. Military planners looked on warily as improving naval and military technologies shortened geographic distances. Preston recounts a number of apocalyptic books that appeared during this period, warning of imminent invasions that would overwhelm the feeble U.S. military, with foreign armies occupying broad swathes of the continent. These potboiler fantasies were overwrought, to be sure, but they reflected something real. Even basic territorial defense would require more resources than it had in the past.

At the same time, it became increasingly difficult to heed the warning against “foreign entanglements,” the most resonant part of President George Washington’s 1796 Farewell Address. Perhaps Americans could still avoid official diplomatic commitments, but the U.S. economy was by now deeply enmeshed in foreign supply chains, export markets, and financial networks. It was around this time that major banks such as J.P. Morgan began actively promoting an internationalist posture, and worked hand in glove with the U.S. and British governments on far-flung ventures across the globe, as chronicled in Ron Chernow’s classic House of Morgan (1990). A conspicuous flaw of Total Defense is that Preston spends far too little time on this latter point, which is key to his argument. Largely because America’s economic interests increasingly extended beyond the continental United States, a new vocabulary of national security became necessary.

Read the rest here.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The Red Planet is an unexplored frontier.

It assumes that clarity on matters of principle precedes consensus.

Resurgent national sovereignty movements are back and validated by expanding electoral mandates.

America should officially recognize it as an independent state.

Artificial intelligence needs to be kept within the bounds of our constitutional order.