Real Classical Education

On recovering basic literacy, stateside and across the pond.

When the history of the Christian Classical Education movement is written, the central figure will surely be Pastor Douglas Wilson. The Association of Classical Christian Schools, which he founded, includes even more member schools than Pastor Wilson has written books—and that is saying something. Over the past half-century, through the institutions and associations he has created, the essays, articles, and polemics he has written, and the sheer force of his personality, Pastor Wilson has helped guide the educations of tens of thousands of Americans.

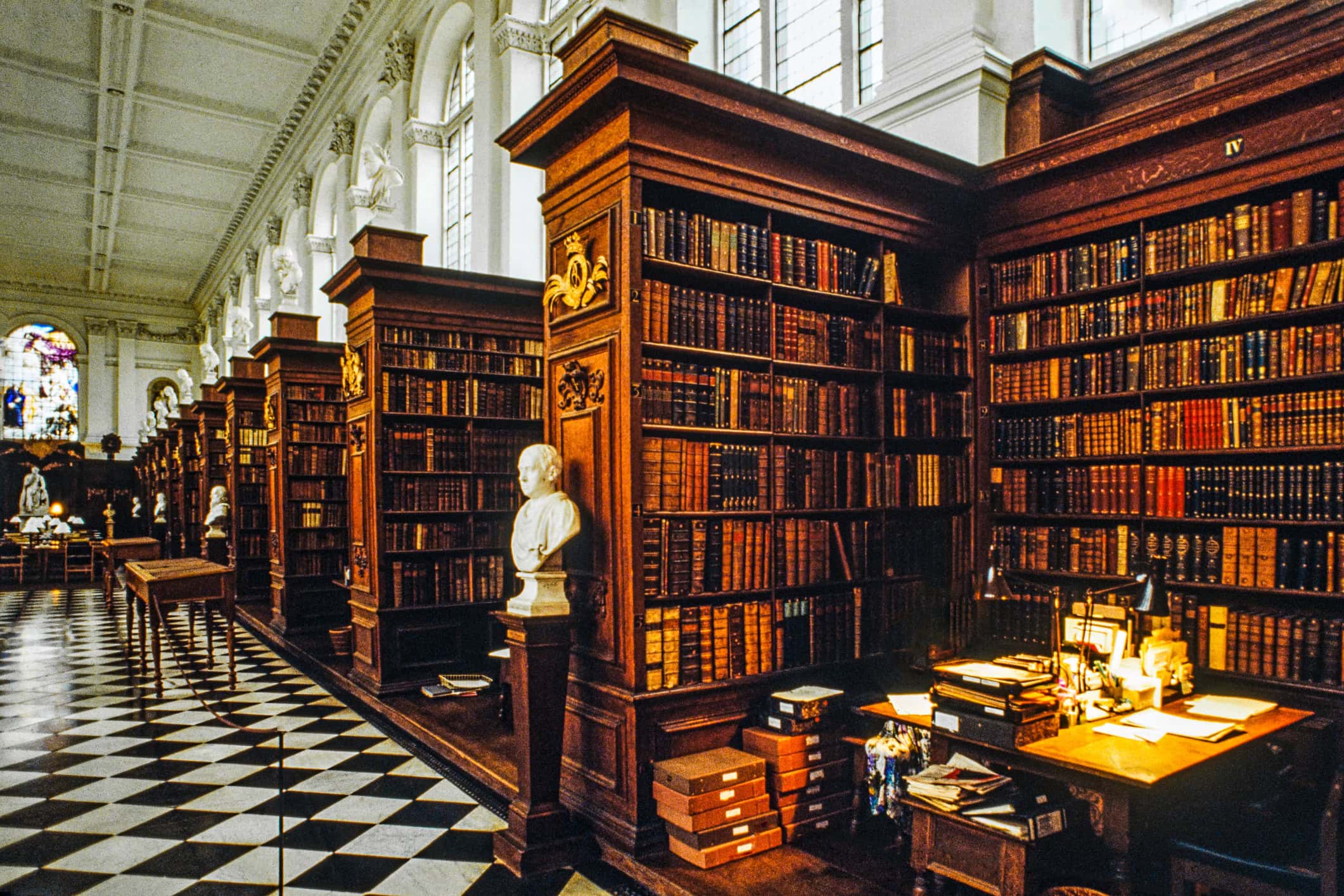

In 1991, Pastor Wilson published Recovering the Lost Tools of Learning: An Approach to Distinctively Christian Education. This book remains the blueprint for Christian Classical Education across America. Its title was inspired by “The Lost Tools of Learning,” a 1947 lecture by Dorothy L. Sayers (1893-1957). Outside Pastor Wilson’s movement, Sayers is mostly known, if at all, as the author of some moderately entertaining detective stories. Her translations of Dante for Penguin Classics are still in print, but so dated as to seem older than the medieval original.

“The Lost Tools of Learning” is the sort of text that one stumbles across randomly in secondhand bookshops, usually after it has been deaccessioned by a university library on account of a conspicuous lack of scholarly interest. It was first presented as a lecture for a summer school in Oxford, and later published as a pamphlet. No doubt Sayers herself quickly forgot about it. She seems to have written it in a hurry: 20 minutes of material is stretched to an hour’s length. Perhaps this is why schoolteachers love it so much.

Educated English people tend to dismiss Sayers’ work, on the rare occasions they condescend to notice it. They also scoff at the Christian Classical Education movement and sneer at the Americans who take part in it. People like Pastor Wilson must seem barbarians to them. But are the English themselves really so civilized these days?

A few minutes’ conversation with a junior faculty member at (say) Cambridge will rapidly cure the most helplessly nostalgic Anglophile of any inferiority complex. Accredited scholars at ancient British universities now seem expert mainly in complex rhetorical techniques for justifying how they managed to spend eight uninterrupted taxpayer-funded years studying English literature without once finding 20 minutes to memorize a single sonnet by Shakespeare. These academics are of course deeply learned, if only in sophisticated tactics to scold and shame you for daring to suggest that they demonstrate any basic knowledge of their chosen subject. Americans would do well to study these tactics, except that such exquisite passive aggression might well be wasted on their own opponents.

If British education has deteriorated in recent decades, even at elite institutions, British culture is an even greater disgrace to the nation’s once-proud traditions. Things were not so bad at the end of the 1990s, when there was still a thriving subculture, at least in tourist-infested cities like London, based around the superficial appreciation of Shakespeare. The now-disgraced Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein deserves special credit for making this sort of middlebrow Anglophilia briefly seem glamorous to mass audiences. His greatest achievement in this respect was the romantic comedy Shakespeare in Love (1998), which remains popular even among people who do not teach English literature, or carry around a “Shakespeare and Company” tote bag from Paris.

Shakespeare in Love was written by Sir Tom Stoppard, who died on November 29, 2025, aged 88. A writer with Stoppard’s wit, intellectual daring, and sheer range of reference simply could not arise today in England: state-funded arts institutions mandate that any material their administrators deem too “difficult” or “elitist” for the masses ought to be dumbed down as a matter of principle. Yet bureaucrats are not the only problem here. In fact, the greatest obstacle to the rise of another Stoppard-like figure might be the British audience as it currently exists.

In winter 2024, the Hampstead Theatre in north London restaged Stoppard’s hit 1997 play The Invention of Love. At the end of the 20th century, when Stoppard wrote the script, much of the audience had studied at least the rudiments of Latin at school. The main character, the Latinist and poet A. E. Housman, was not simply some exotic eccentric: he and his work were part of English national culture. Today, by contrast, perhaps a thousand or so high school students per year nationwide sit for the A-level exam in Latin. Only old people remember Housman’s lyrics. After three decades, The Invention of Love has become too demanding for audiences to whom Housman’s world now seems as quaint, twee, and alien, as it would to the people who eat at Waffle House.

What happened? The short answer is that educational “reform” happened. If you look at the English literature curriculum for state-run schools in the United Kingdom between, say, 1945 and 1965, you see reading lists for 15-year-olds that include generous selections of Chaucer and take in the full range of the literary tradition in verse and prose. But things have changed in ways that cannot be blamed on social media, AI, or “white privilege.”

Today, the English literature requirements for GCSE (equivalent to the 9th and 10th grades at an American school) include one Shakespeare play, one 19th-century British novel, one post-1914 literary work, and 15 poems. This looks even less demanding when you learn that the most widely taught 19th-century novel in British state schools is A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. At GCSE level, “modern literature” tends to be represented by J. B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls, a creaky drawing-room drama that was first performed in the Soviet Union in 1945. As for the exams themselves, questions are designed to facilitate thoughtless teaching and lazy marking. This is no better than the literary training to which most Americans are currently subjected. Indeed it may be worse in a few respects, not least the insidious ways in which it regulates thought.

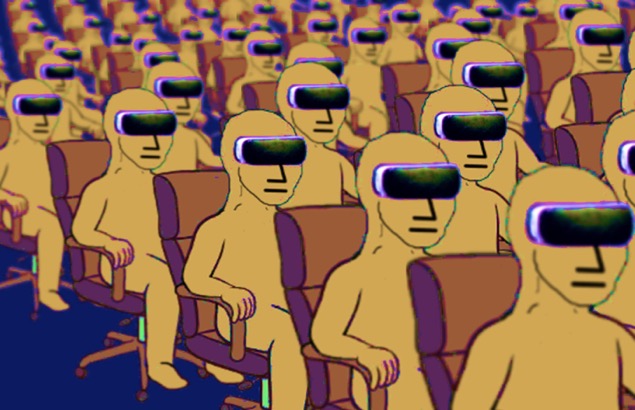

Mass education along these lines makes literature seem at once frivolous and joyless, not to mention pointless. Since at least the Second World War, education throughout the English-speaking world has found itself increasingly in the grip of statist, utilitarian, and scientific-materialist ideologues. Why cultivate the soul, these constipated-looking people ask, when none exists?

In America, the Association of Classical Christian Schools boasts well over 500 institutions on its list of members. Could Christian Classical Education on an American model help halt or reverse the decline of British culture? Any such movement would face an uphill battle, of course. British society is largely “post-Christian” thanks in no small part to the Church of England, which has degenerated into a national embarrassment. Thus “Christian” might need to be dropped from the name of any such movement, for the moment anyway.

As for classical education in the traditional sense of the description, not only has instruction in Greek and Latin diminished catastrophically since the 1960s; indeed, the very principles underlying humanistic education have all but evaporated, even at the most prestigious schools. Tom Stoppard wrote The Invention of Love with no higher educational qualification than an A-level in Latin from an obscure school in Yorkshire. Today, by contrast, it is not unheard of for someone with A-levels in Greek and Latin from a famous (and expensive) school and a B.A., MPhil, and Ph.D. from Cambridge—all in Classics—and a postdoctoral fellowship in Classics at an Oxbridge college to be functionally illiterate in the ancient languages, and incapable even of teaching them at an elementary level.

A promising intervention in the current crisis was released on November 20, 2025, by the Civitas Institute for the Study of Civil Society, which is based in London. The researchers Briar Lipson and Daniel Dieppe have compiled a report entitled Renewing Classical Liberal Education: What It Is and Its History, outlining a set of proposals for renewing British national culture by decisively redirecting education toward something other than mindless preparation for meaningless exams. This will all look suspiciously familiar to anyone who has read Recovering the Lost Tools of Learning—minus the Calvinist theology, of course.

As Dieppe and Lipson note in their introduction:

It is still perfectly possible to pass through school, including with flying colours, having never picked up a work of classical literature, having never considered the nature of truth, without the basics of Western chronology, with not one line of poetry committed to memory.

Lipson and Dieppe have convincing ideas, which they express in language that will not alarm the doughy, lanyard-wearing civil servants and administrators who could potentially implement the plans outlined in Renewing Classical Liberal Education. This is why they play down the Christian element in their thinking and speak of Maya Angelou in the same breath as Saint Thomas Aquinas: because it would be tactically imprudent not to. This is an ugly compromise, to be sure; but Lipson and Dieppe do not have a choice, unless they want to sabotage their own project and wallow masochistically in defeat, as those who call themselves “principled conservatives” seem so fond of doing.

Renewing Classical Liberal Education is not merely an exercise in nostalgia, or a quixotic attempt to ensure that people can get the references in Tom Stoppard’s plays. As a character famously declares in Stoppard’s 1983 comedy The Real Thing:

I can’t help somebody who thinks, or thinks he thinks, that editing a newspaper is censorship, or that throwing bricks is a demonstration while building tower blocks is social violence, or that unpalatable statement is provocation while disrupting the speaker is the exercise of free speech…. Words don’t deserve that kind of malarkey. They’re innocent, neutral, precise, standing for this, describing that, meaning the other, so if you look after them you can build bridges across incomprehension and chaos. But when they get their corners knocked off, they’re no good anymore…. I don’t think writers are sacred, but words are. They deserve respect. If you get the right ones in the right order, you can nudge the world a little or make a poem which children will speak for you when you’re dead.

The success of Pastor Wilson’s vision speaks for itself. Even those who are hostile to elements of his theological vision have been happy to adopt and adapt his work. As for Lipson and Dieppe, their proposals in Renewing Classical Liberal Education have a high chance of being successfully implemented on a national scale in the United Kingdom, once there is a change of government. What about America? Can Classical Liberal Education provide a viable alternative to an explicitly Christian program, either in anti-Christian jurisdictions or for the benefit of parents who are, for whatever reason, skittish about the uncompromisingly religious nature of Pastor Wilson’s vision?

Americans—even those who are not Anglophiles—might be aware that the English aren’t alone these days in having a dilapidated national culture that urgently needs renovation. Arguments about the future of education cannot be treated like speculative after-dinner disputes. There are wrong answers to these questions as well as correct ones, and heavy penalties involved in not getting them right. On that point, at least, we may all agree with the Calvinists.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

It’s time to bet on humanity—before things get worse.

South Dakota’s experience with intellectual diversity legislation is a case study for the nation.

I will arise and go now.

Democrats are preparing to win by any means necessary. What’s the Right going to do about it?

There is a reason why we love to drive.