An English literature professor describes how he came to love teaching Freshman Comp.

Rage Against Reading

Schools should treat children and our literary legacy with equal respect.

Active discrimination against boys in American schools has been a raging problem for decades. In The War Against Boys, published in 2000, feminist author Christina Hoff Sommers observed that the educational establishment treats boys as defective girls. Since then, opinion makers have been counting the ways in which our academic establishment sets up boys for a lifetime of failure.

These takes are hard to argue with. The latest look at how K-12 education sidelines boys comes from Tom Sarrouf, Jr. at the Institute for Family Studies. Sarrouf’s work is based on the “What Kids Are Reading” report for 2024 by Renaissance, an educational NGO with global reach and a proud commitment to the principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Renaissance compiled a comprehensive survey of popular books assigned to American students by grade level.

Sarrouf found that fiction is over-assigned in K-12—very few non-fiction titles appear among the top titles in the report. Citing several recent studies on the reading preferences of children of the opposite sexes, Sarrouf notes:

Boys were more interested in war, comedy, sports, and science fiction, and more excited about informational texts, whereas girls preferred narrative books and romantic stories…boys are also far less likely to read books by female authors or with female protagonist, but girls were willing to read books written by men and with male protagonists.

Sarrouf’s answer to the bias includes “rebalancing of reading material in schools specifically targeted at boys.” The project would involve assigning more non-fiction in science and history and “making appeals to books with male protagonists” in English.

I tend to disagree with the first part of his advice—and not only because students are already reading science and history. Common Core curriculum includes non-fiction assignments in English classes—the very discipline that is supposed to be dedicated to the life of imagination. I very much like the idea of adding male protagonist fiction, even if we already have quite a few of them on the Renaissance lists. It includes everything from Harry Potter to Diary of a Wimpy Kid—the latter book is assigned liberally from elementary to high school.

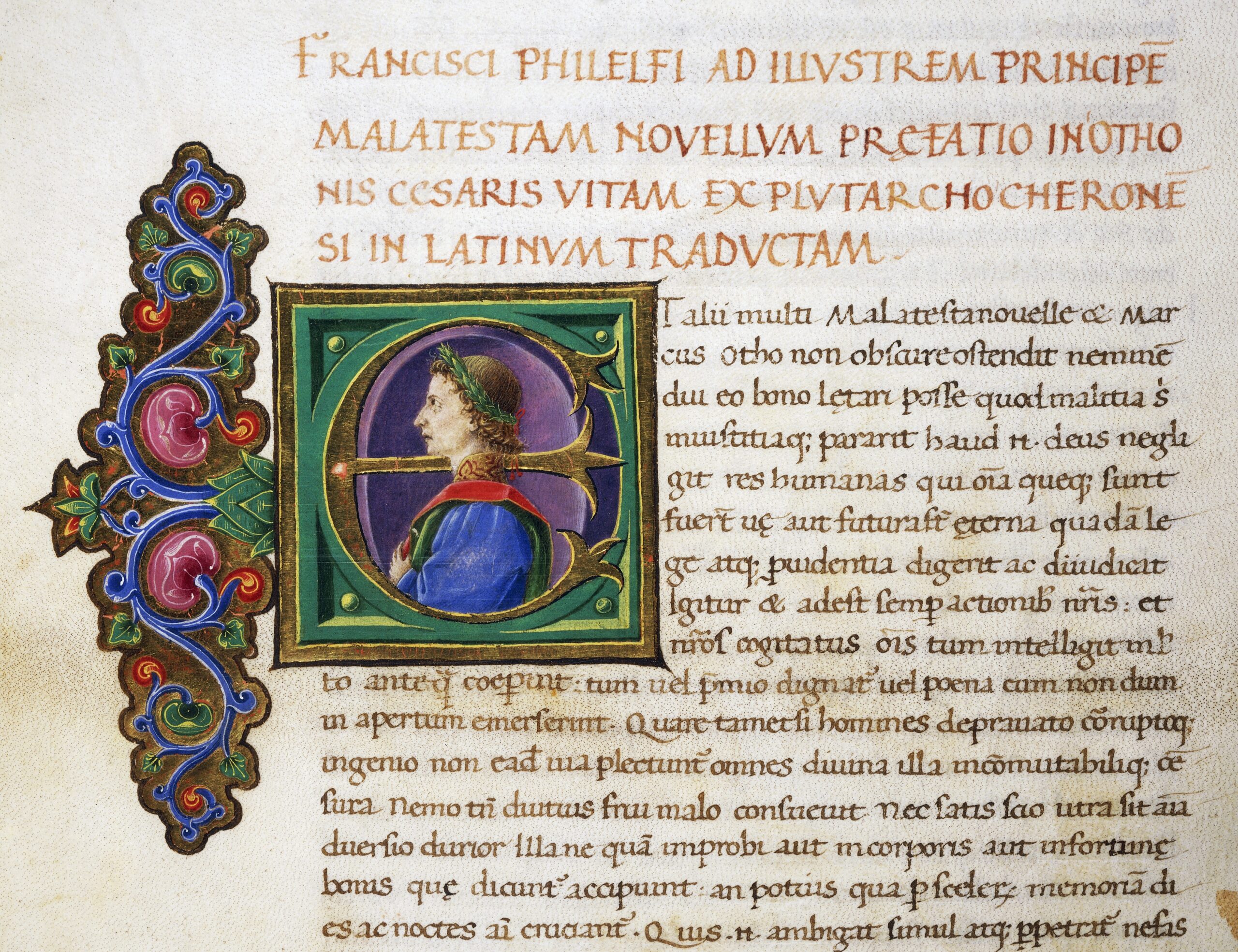

When I look at the top books read in American schools I’m struck by three features—the near-absence of classics, especially in elementary and middle school, the near-absence of folklore and fairy tales, and the near-absence of poetry. We don’t need to reinvent the wheel. Restoring these three categories to their proper place can improve education immensely. In the interest of conserving space, I’m going to leave out a discussion of poetry and focus instead on sex roles and traditional reading lists.

Classic books are filled with captivating male protagonists. I grew up devouring Mark Twain, Alexandre Dumas, and many others while reading at home. When I was a kid in the Russian-speaking part of the USSR, it was a given that if a child—a boy or a girl—is a reader, he would read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

Nothing of that nature is expected of American kids. Here, it’s assumed that The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is a better book. It was certainly influential; Ernest Hemingway once declared that “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.” However, this doesn’t explain the phenomenal success of its predecessor the world over. The themes of race, class, and slavery, which elevated Huckleberry Finn into high school and college curriculums, were present in Tom Sawyer, and Tom has much more than that. Twain tells stories of a middle-class rebel child living by wits and daring—from his first efforts to cross the big river to courting a judge’s daughter. What can be more American than that?

To be fair, I originally read Tom Sawyer translated into modern Russian. Yet the Southern vernacular sprinkled through Twain’s narrative is no insurmountable challenge. I find it strange that teachers don’t see it as their job to connect the next generation of Americans to their heritage, preferring to submerge students into the sea of forgettable contemporary titles rather than explaining complicated language and showing their students how to love historic writing.

I can’t say I enjoyed the book for the use of the vernacular; an American reader would appreciate it as an artifact of history. I liked the character of Tom, but it’s the presence of Becky Thatcher that made the book such a captivating read—and something entirely missing from Huck Finn.

Romance entices the female reader regardless of the sex of the protagonist, but in contemporary titles with female leads, love stories are giving way to empowerment. The Renaissance report reveals that the reading curriculum barely includes Jane Austen—the great English writer only appeared once, with Pride and Prejudice, for twelfth graders—and the Brontë Sisters are absent. Girls might be having an easier time with the literature curriculum, but it’s a mistake to conclude that it’s female friendly.

This project of cultural revolution is not limited to public schools; romance has been substituted for girl-boss messages in film and games. Disney, which long served as an American girl’s gateway into folk narrative, is diligently eradicating heteronormative plot lines and turning love interests of princesses from dragon slayers into goofballs.

I remember reading multiple stories from Afanasiev’s collection of Russian folk tales in elementary school—and that’s in addition to Leo Tolstoy’s and Nikolai Gogol’s writing that was inspired by folkloric themes. American schools don’t approach the genre systematically. Renaissance reports that the Disney version of Beauty and the Beast is assigned to second graders. Contemporary takes on the beloved stories do exist—The True Story of the Three Little Pigs, apparently popular among third grade teachers, and Percy Jackson’s rendition of ancient mythology is on the list for sixth grade. Horror stories and urban legends appear popular with middle-school readers. The idea behind the assignments is apparently to throw some titles at the kids in the hope that they’ll read, not to teach them to love the great achievements of their civilization. Because there is no purpose in teaching folkloric material, its beauty gets scrambled.

Consequently, both boys and girls lose out on the poignancy of sex roles. As I mentioned in an essay on the rapist Prince Charming controversy that flared up a few years ago, boys actually fare better with cinematic tales—the childhood canon includes, for instance, the space age fairy tale Star Wars, with its great plot, fascinating details, and solid characters, both male and female. At the same time, female-centered tales became the subjects of never-ending reinventions and are stripped of meaning.

It’s too early to tell if the culture wars, with their constant demands on female characters, contributed something enduring to English language literature. Already, the social outcomes do not appear promising—we have a generation of obedient girls maniacally throwing themselves into politics.

Far from being male-dominated or crafted exclusively for female consumption—and historically the novel was developed for the audiences of women—many classic texts appeal to both sexes. The best example is Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, which figured into the Renaissance report as a “high level book,” despite being assigned to every 15-year-old student in Russia. In my high school years, we often heard that the chapters about war appeal to boys and the chapters about peace are more interesting to girls. Tolstoy examines the roles of men and women in history—and does so in ways that are far from obvious. I keep wondering if his hero, Pierre Bezukhov, was autistic, and I would rather have my child read two volumes of Tolstoy than any series about a special needs or nerdy kid growing up.

Not to dunk on any living authors, but they have yet to prove their staying power. Plus, our children need to learn to relate to their heritage, and part of this program is examining historical sex roles. I have many reasons to want to return the English language canon to our educational institutions—with some key works translated from foreign tongues—understanding that the ways to be men and women is one of them.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The war in Ukraine is not an excuse for russophobic iconoclasm.

Reject the fiction of perfection for the messiness of the world outside your head.

The 50th anniversary of a classic adventure novel provokes reflection on a romantic yet gritty aspect of modern warfare.

If you’re making a list, you’ve already lost.

“Thank God for being an American.”