"Relativism," contra Jaffa (and Bloom), was merely administrative compromise. But the academy no longer believes all sin is relative...

Our New National Creed

Wokeness looks, smells, and feels like a religion, so let’s force the courts to treat it as one.

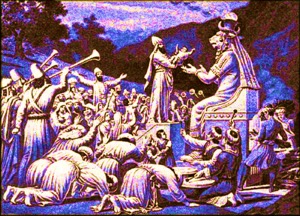

On March 18, 2021, the California State Board of Education approved an Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum that required students to chant a prayer invoking the names of five Aztec deities, whose cultus featured ripping hearts from the chests of living humans, exsanguination and cannibalism, and whose priests performed their duties clad in the flayed skin of sacrificial victims. Teachers were to use the chant as a tool to “challenge racist, bigoted, discriminatory, imperialist / colonial beliefs” and inspire students to “build new possibilities for a post-racist post-systemic racism society.”

As we all sense, although some hesitate to pronounce judgment, more than ideological appropriation is at work here. At a moment when campuses have become madrassas, rainbow flagged-churches host bizarre performances, and neighborhoods nationwide proclaim the new creed with standardized signage in windows and yards, Americans are recognizing that, whatever we variously mean by “religion,” wokeness qualifies. It boasts priests and congregations, canons and temples, mendicants and orders, idols and gods. Disputes over taxonomy notwithstanding—is it a quasi-religion? a political religion? a new religion or merely a degenerate, warmed-over Protestantism?—it has arisen to lay claim to spirit, body, and body politic with the same totality as many of history’s oldest faiths.

In fact, from a certain standpoint, wokeness is older than it seems. Eric Voegelin would recognize it as a species of “parousiastic Gnosticism,” the aim of which “is to destroy the order of being, which is experienced as defective and unjust, and through man’s creative power to replace it with a perfect and just order.” It is an apocalyptic faith which envisions a wholly immanent eschaton. Despite its fetishization of indigenous paganism, it is Protestant millenarianism sans-Christ. N.S. Lyons, the pseudonymous writer of The Upheaval, effectively summarizes the theological structure of the woke creed:

The world is divided into a dualistic struggle between oppressed and oppressors (good and evil); language fundamentally defines reality; therefore language (and more broadly “the word”—thought, logic, logos) is raw power, and is used by oppressors to control the oppressed; this has created power hierarchies enforced by the creation of false boundaries and authorities; no oppression existed in the mythic past, the utopian pre-hierarchical State of Nature, in which all were free and equal; the stain of injustice only entered the world through the original sin of (Western) civilizational hierarchy; all disparities visible today are de facto proof of the influence of hierarchical oppression (discrimination); to redeem the world from sin, i.e. to end oppression and achieve Social Justice (to return to the kingdom of heaven on earth), all false authorities and boundaries must be torn down (deconstructed), and power redistributed from the oppressors to the oppressed; all injustice anywhere is interlinked (intersectional), so the battle against injustice is necessarily total; ultimate victory is cosmically ordained by history, though the arc of progress may be long; moral virtue and true right to rule is determined by collective status within the oppression-oppressed dialectic; morally neutral political liberalism is a lie constructed by the powerful to maintain status quo structures of oppression; the first step to liberation can be achieved through acquisition of the hidden knowledge of the truth of this dialectic; a select awoken vanguard must therefore guide a revolution in popular consciousness; all imposed limits on the individual can ultimately be transcended by virtue of a will to power.

The advent of a new religion, especially one as aggressive and evangelical as this, has not only political consequences, but legal ones too. In Woke Racism, John McWhorter, who contends that wokeness “actually is a religion,” speculates that “in our times, it will feel unwelcome to the Elect,” as he theologically terms the woke, “to be deemed a religion, because they do not bill themselves as such and often associate religiosity with backwardness. It also implies that they are not thinking for themselves.” But woke religiosity has already moved beyond old-Left objections to the mentality of devotion. Free thought and free speech, the woke avow, are mere covers for the worst of ethical sins. If they continue to avoid the religious label, it is for the fundamental reason that the Constitution is incapable of stopping their conquest of public life and law so long as they remain officially an non- religious movement. Having long sought to drive religious ideas and persons from the public square, the woke understand that if the label gains purchase, they might be driven out as well.

Thanks to the vast legal and bureaucratic infrastructure that arose to enforce the revision of the social contract effected by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, wokeness is embedded in all our public institutions. As Christopher Caldwell demonstrates in his recent book Age of Entitlement, these transformations amounted to a revolution whereby the professional-managerial class supplanted the Constitution of the Founding with a de facto constitution of their own, whose animating force is now the woke worldview. Wesley Yang, to emphasize its status as a usurper, anointed this worldview the “Successor Ideology.” As Joshua Mitchell shows in American Awakening, his own book on the matter, this strain of Left ideology has shifted decisively from the ground of modern philosophy to repurposed categories of Christian thought. The Successor Ideology has transformed itself into a Successor Theology.

Under any honest reading of First Amendment jurisprudence, the sweeping institutionalization of this creed in our agencies and arms of government, penetrating with virtually unlimited claims into the spheres of both public and private life, amounts to an establishment of religion. If opponents of wokeness take their own criticisms seriously, they should demand the Successor Ideology be recognized as a religion under federal law—and its unconstitutional establishment challenged accordingly.

It would appear Congress has never attempted to define an emergent ideology as religious. Nor has the Supreme Court taken up a case in which an ostensibly secular ideology was accused of violating the Establishment Clause. Yet just such an endeavor is constitutionally licit and, if Republicans take Congress or retake the presidency, politically achievable.

The Supreme Court has had little to say about what constitutes a religion under the establishment clause, for obvious reasons. When, for example, Trinity Lutheran Church sued the state of Missouri for denying their parochial school a grant for playground resurfacing, all parties and the Court took for granted the religious character of the institution. But the Court has had to venture definitions when deciding free-exercise cases, and its definitions have been quite inclusive. In Torcaso v. Watkins (1961), the Court countenanced “religions in this country which do not teach what would generally be considered a belief in the existence of God,” such as “Buddhism, Taoism, Ethical Culture, Secular Humanism and others.” In United States v. Seeger (1965), the Court ruled that for the purpose of assessing conscientious objection to military service, religious belief, as opposed to “essentially political, sociological, or philosophical views,” is “belief that is sincere and meaningful” and “occupies a place in the life of its possessor parallel to that filled by the orthodox belief in God…”

The expansiveness of these definitions is significant because “religion” in the First Amendment’s free-exercise clause is identical to “religion” in the establishment clause. As a simple matter of grammatical and logical necessity, the Court must apply the same definition to both clauses. If the Court defines “religious belief” as broadly as it did in United States v. Seeger, the woke creed inarguably qualifies. But this remains true even if more precise definitions are used. Émile Durkheim, in The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, called religion “a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them.”

Or consider Robert Cummings Neville, for whom the final essential element of religion, after cosmology and ritual, “is that a tradition have some conception and practical procedures for fundamental transformation aimed to relate persons harmoniously to the normative cosmological elements, a path of spiritual perfection.” The woke creed possesses not only a well-developed metaphysical cosmology, but protocols for spiritual purification, such as myriad methods for expurgating one’s whiteness. In the summer of 2020, Nancy Pelosi and other Democrats performed such a ritual cleansing when they draped themselves in kente cloth and knelt for eight minutes and forty-six seconds in reverent imitation of Derek Chauvin.

The clerisy of the Successor Ideology is decentralized, of course; some adherents prefer the Gospel According to Ta-Nehesi Coates as opposed to Ibram X. Kendi or Robin DiAngelo. But many religions lack a centralized hierarchy. Falun Gong, for example, is no less a religion for lacking official leadership. Nor is Hinduism. At first blush, it may seem difficult to distill all the varied concerns of the Successor Ideology into a consistent worldview. But although the intersectional coalition is riven by competing interests, even irreconcilable differences (e.g., the feud between Clintonite neoliberals and quasi-communist Bernie Bros), every member must genuflect before a shared sacred narrative—and those who represent or embody it.

Thanks to a lawsuit filed by California parents who argued it constituted an establishment of religion, the State Board of Education was forced to remove the Aztec chant from the ethnic studies curriculum. This was a meaningful victory. But it left untouched the curriculum’s guiding religious worldview. There are many ways to ensure the woke religion is recognized for what it is in our body of American law. One path, for instance, could amend the Civil Rights Act of 1964, using language similar to Lyon’s, to make explicit that the Act may not be enforced according to woke interpretation. This would precipitate a cascade of consequences: Offices of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, to the extent that they establish the woke religion, must be dissolved. Federal support for woke nonprofits must be rescinded and woke criteria may no longer be used by federal programs to apportion grants or make hiring or promotion decisions. Legislators who use woke criteria in confirmation hearings (for judicial appointees, cabinet positions, etc.) should be censured for utilizing a religious test for public office. Public primary and secondary schools must jettison woke elements (such as lessons derived from critical race theory, queer theory, etc.) from their curricula or else lose access to federal funding. Public universities must no longer enforce woke values among students, faculty, or staff (e.g., through adherence to Obama era rules for Title IX adjudication), and they must begin adhering to the original public meaning of Title VII, as excluding the Successor Ideology—and thus woke metaphysics—from wielding interpretive authority would effectively nullify the ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County (2020).

There would be immediate consequences in the private sphere as well. For example, private employers whose hiring decisions or company policies enact the woke religion could be more easily sued by employees for discrimination or for fostering a hostile work environment. Exposure to such liability could effect a sea-change in corporate culture, perhaps spelling the end of woke capital.

Without question, resistance to these measures would be spectacularly intense, at least initially. But even if legislation or lawsuit or executive order were to fail, the attempt would still have a tremendous impact on the national consciousness. The louder the woke deny the religious character of their movement, the more transparent the power dynamics of the “secular” state will become. As any good genealogist of ideas knows, our concept of “religion” as a genus containing different species emerged in the early-modern period for the purpose of excluding certain groups of people from holding public power, thus enabling monarchs to consolidate authority. An honest definition of “religion” in the modern period would be: “that which the sovereign excludes from wielding power.”

The opposition of the woke faithful to being confirmed as adherents to a religion—rather than as data-driven sociologists or ethics-driven activists—would reveal Wokeness as a play for power at the highest and most warlike level of civilization—meriting, albeit peacefully, a broad-based response in kind.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The longing to universalize the college lifestyle has turned academia into a church of hypocrisy.

Today’s fraudulent multiculturalist faith fragments society—and fractures the psyche.