Biden's historians fantasized about FDR, but the reality will be closer to Carter.

Currents of History

Putin’s surprising exegesis on the Russian past strikes a deracinated people as perverse.

Well, that was weird. Even Tucker thought it was weird. He was the first person to say so, in fact.

Not long after his interview with Putin, while he was still in the Kremlin waiting to leave, Tucker Carlson expressed his genuine surprise at what had just happened. He had clearly been expecting “another interview” with a powerful political leader, full of recent history and familiar justifications and appeals to right and hypocrisy. What he got was something very different indeed—as I’m sure you already know.

“That was quite an interview,” Tucker said in a short video that later made its way on to Twitter. “It began in a way I didn’t expect at all.” He had been annoyed, frankly, at how Putin responded to a simple question about his motivations for invading Ukraine: not with a simple answer, but with an “extremely detailed history going back to the ninth century, of the formation of Russia, from the tribes into the nation, and Ukraine’s part in that—and the Rus and all that.” Tucker only became more annoyed when Putin failed to respond to prompts to give a “specific answer,” instead continuing with his long journey through the many centuries of Russian history up to the present day. “I thought he was filibustering,” Tucker said. That single answer, with irritated interruptions, lasted more than half an hour, a full quarter of the interview.

Real clarity about what Putin was doing only came after the interview had finished, when Tucker watched the interview back and realized that the ancient history of Russia, and Ukraine’s integral part in it, is a genuine motivation for Putin’s conduct of the war. Putin’s rambling, filibustering answer was actually “a window into how he thinks about the region.”

Tucker expected harsh criticism for traveling directly to Russia to meet the man many consider to be the closest thing we have to a latter-day Adolf Hitler—Adolf Putler, as my friend Bronze Age Pervert calls him. The subsequent denunciations and cries of “traitor” and “Russian agent” can’t have shocked Tucker; though the, apparently serious, proposal to ban him from the E.U. probably did. Given his own bemusement at Putin’s focus on what we might politely call “ancient history,” Tucker must also have expected viewers in the West to react with similar disbelief to Putin’s justifications. And of course, they did.

By grounding his argument in the deep past, it seems Putin was effectively conceding defeat on principle. After all, what does the Kievan Rus have to do with modern Russia or Ukraine or anything else for that matter? Who cares about Prince Rurik or Volodymyr the Wise or what the Ottomans or the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth did or didn’t do hundreds of years ago? This is 2024, not 1024, 1724, or even 1924.

Unlike Tucker, the critics could see no value in what Putin had to say. Putin’s answers were a window, yes, but only into the mind and soul of a tyrannical madman who would say anything to clothe his naked will to power.

For a glorious few days after the interview, Twitter was awash with Putin-Tucker memes, many quite hilarious, sending up Putin’s insistence on returning to the earliest days of Russian history to explain current events. We had Putin expounding on the creation myth of Tolkien’s Middle Earth; on why the chicken crossed the road, with reference to the first domestication of red junglefowl in ancient Burma, 6,000 years ago; on the beginnings of the American Civil War in the arrival of the Saxon warlords Hengist and Horsa in post-Roman Britain in 449. Never one to miss an opportunity for a bit of meme magic, I suggested that Putin had also included an excursus on the origins of the lipid-heart hypothesis in his long answer to Tucker and that, after the interview, he had phoned Tucker because he had missed out on an important part of his story: the origins of Russian sour porridge at the siege of Belgorod in 987.

But now that the laughter has died down, we ought to recognize that there’s a lesson here, and it’s not one about the excesses of tyranny. The lesson isn’t even about Putin. It’s about us. Tucker seemed to grasp it in the immediate hours after the interview, and no doubt he grasps it more now, over a week later. The lesson, I think, is this: the West is divorced from its own history in a way that may be unique in history, and that, far from being a great strength, this is in truth a stunning weakness.

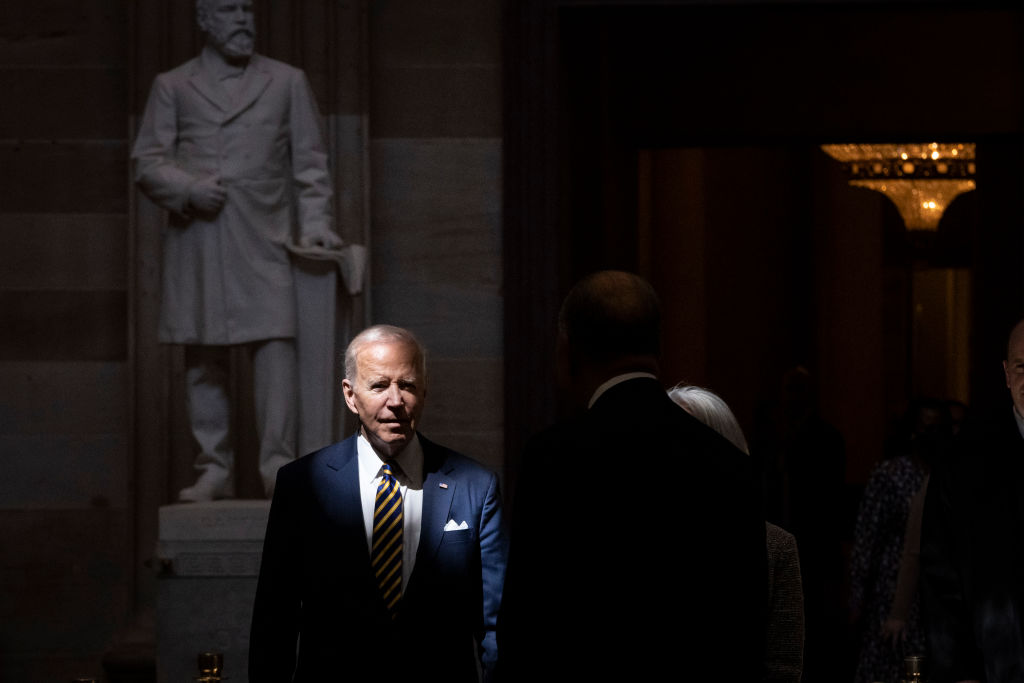

It’s not simply that a leader like Biden couldn’t speak about America’s history for 30 seconds, let alone 30 minutes: the dementia, exacerbated by statins, has put paid to any hope of a coherent message leaving the current president’s mouth ever again. Rather, it’s that Biden wouldn’t even if he could. This isn’t how Western leaders speak about their nations, and it’s not how we’re supposed to think about our nations either, or indeed about ourselves.

That something is missing at the very heart of our way of life, and that this absence has the potential to lead us catastrophically astray if it hasn’t already, is not a new or original idea in Western thought. It’s an idea that’s present even in what is often considered to be the most shameless piece of Western triumphalism, Francis Fukuyama’s book The End of History and the Last Man. The book is not merely a celebration of all the ways that modern liberal democracy is wonderful and better than all other forms of government that have ever been created or ever could be created. Rather, The End of History is also a warning about the inability of democracy to satisfy man’s most basic desires. Above all, Fukuyama warns us, democracy cannot satisfy man’s need to distinguish himself from others, a need the ancient Greeks called megalothymia. People very readily forget this final part of the book, for some reason, even though it runs to a fifth of the book’s total length.

Thymos, according to the Greeks, was the part of an individual’s soul that seeks recognition or dignity. The word might be translated as something approximating “spiritedness” or “warm-bloodedness.” What’s important is that it’s an attribute all men possess and can develop. The Greeks believed it came in various forms. There was isothymia, a desire to be acknowledged as equal to everybody else. This can be seen as the central impulse at the heart of the Christian and democratic ideals. Then there was megalothymia: the desire to seek distinction above others, in opposition to isothymia. At the liberal democratic End of History, a place where all men are judged, a priori, to be equal, isothymia is the default, and megalothymia can find no real, lasting outlet.

This is where the Last Man of the book’s title, a character first identified by Friedrich Nietzsche, comes in. The Last Man is the product of the long triumph of Christianity, which culminates in liberal democracy. As Fukuyama explains,

Nietzsche’s Last Man was, in essence, the victorious slave. [Nietzsche] fully agreed with Hegel that Christianity was a slave ideology, and that democracy represented a secularized form of Christianity. The equality of all men before the law was a realization of the Christian ideal of the equality of all believers in the Kingdom of Heaven. But the Christian belief in the equality of men before God was nothing more than a prejudice, a prejudice born out of the resentment of the weak against those who were stronger than they were.

Put simply, the Last Man is what you get at the End of History, when there’s no longer anything particularly important worth living for. When the great ethical, economic, and political questions have all been settled, what higher purposes exist for men to strive toward? None, it would seem. And so, without an outlet for genuine striving, life becomes dull on an ontological level. While this may be enough for some—for those who can fit themselves into the position of the archetypal latter-day consumer—for others, it may prove too much to bear.

In Civilization and Its Discontents, Sigmund Freud cautioned that, when an entire population has unfulfilled or even deliberately suppressed desires, turmoil will follow. This is the crux of Fukuyama’s warning about the End of History: man’s nature cannot be denied, and if it is, there will be trouble. While it’s entirely possible that man will be happy now as one among many billions of equals, each pursuing his own limited goals like making money, buying stuff, having sex, and going on holidays, it’s equally possible that man, or rather some men, will rebel in the name of satisfying their desire to be different—to be better. What we might see instead of a future of satisfied dolts enjoying an easy contentment is “immense wars of the spirit”—and Fukuyama means, quite literally, wars—with wild men letting loose and painting the world red again in the name of personal glory and some higher purpose, whatever that might be, just anything other than endless, monotonous peace and sex and commerce.

The Last Man believes he lives outside History. He has no place for it. And that’s us, says Fukuyama, right now. And that, I think, is why we can’t understand Putin and his long discourses on Russian history. It’s also why we face annihilation.

One potential consequence of our new, ahistorical way of life is not just massive dissatisfaction among sensitive young men: It’s eternal self-effacement. It’s happening at this very moment. As Renaud Camus makes clear, the total disappearance of the native peoples of Western countries—which he calls “the Great Replacement”— is not possible without a profound forgetting, a total self-alienation from notions of people and place. A people’s history disappears first, before the people itself.

As I like to say and repeat, a people who knows its history and who knows its classics, a people who knows itself and knows what it owes itself, does not let itself be led—except in the case of open tyranny, armed constraint, and rampant terror—into the unspeakable abysses of history. But stupefaction dispenses with the need for terror, intensive entertainment returns patent dictatorship to the prop room.

Camus, rightly, discards the notion of a grand “conspiracy theory” behind the Great Replacement and instead suggests that it is industrialization, scientific management, mass entertainment, and, of course, democracy that have combined to turn the peoples of the world, and not just Western nations, into interchangeable things with no unique identity, to be moved around and swapped at will by powers beyond their control. Nevertheless, because the movement of people—the replacement—only takes place in a single direction, the victims of this process are the peoples of the West, who are subject to an onslaught of mass immigration that threatens to erase them from history forever.

Camus believes that a “Little Replacement” preceded this Great Replacement. This was a long period of profound cultural decline in which the old aristocratic values of Western civilization, including the assumption that natural inequality, talent, and hierarchy were both necessary and good, values that had been preserved by the bourgeoisie, were challenged and then overthrown by a radical new leveling tendency. Changes in public education, as well as mass entertainment, have been particularly to blame. First individuals become replaceable, one with another, and then whole peoples. This is the essence of the attitude Camus calls “replace-ism.”

But maybe the roots of this attitude run even deeper than the last century or so of modern mass democracy. According to the Russian philosopher Aleksandr Dugin, the forces that are destroying the West and severing it from its own identity and traditions can be traced back to the Middle Ages, to the universities of Europe and the emergence of a doctrine called “nominalism.” In contrast to the opposing doctrine of “essentialism,” nominalism holds that there are no natural categories, only conventions. As a result, all forms of identity are believed, in the final instance, to be arbitrary forms, chosen by humans to make order out of chaos.

The immediate effects of nominalism’s victory in the ivory towers of medieval Europe were pretty mild, although nominalism was briefly banned by the papacy, but in the long run it placed at the heart of Western history a kind of divine “liberating” impulse, a goal to break the shackles of successive forms of convention rooted in all modes of group identity—religious, ethnic, national, social, economic, gender-based, even species-based identity. The Reformation, the Enlightenment, the rise of the bourgeoisie and liberal capitalism, the challenge to liberal capitalism from communism and fascism, the defeat of both and the unipolar moment of 1989, globalization, transgenderism, and now transhumanism—each of these stages of “liberation” in the history of the West and then the world, one after another, fulfills the logic of nominalism, until at last, with transhumanism, we are left with a single form of substantial identity to be freed from: being human itself.

As esoteric as all of this may sound, and as wary as we might wish to be about mono-causal explanations, these accounts, which are so similar in many important ways, alert us to the obvious fact that the causes of the deep and profound changes that have taken place in the Western world are themselves deep and profound. Many critics of those changes from the Right, most notably the so-called “post-liberals,” would have us believe they are nothing more than the result of liberalism, or a gross caricature of it, and that the answer is to ditch liberalism and replace it with some new “collective” vision that is more respectful of “traditional” values and mores. And so, for example, we have Patrick Deneen arguing in favor of a new “multi-racial working-class coalition” united by “Aristopopulism” in books like Why Liberalism Failed and Regime Change.

But an “Aristopopulist regime-change” is just the Great Replacement under another name. It is a rejection of the fundamental history and identity of America, and it relies on the importation of foreign peoples for its plausibility and success. Deneen’s vision would not be possible without the massive demographic changes that have taken place in the U.S. since 1965, as a result of the Hart-Celler Act, the Reagan amnesty for illegals, and now the insanity of the Biden Administration and its open-doors border policy.

Post-liberals make the grave mistake of thinking that liberalism—social and economic individualism, the truncated nuclear family, social mobility, and the emphasis on freedom of association over ties of blood—is somehow an alien imposition, an ideology that has perverted the way Americans live and think and that can therefore be thrown off at will. The truth is very different. Liberalism, as a philosophy, is a codification of the way that northern Europeans, and in particular the peoples of the British Isles, and especially the English, had been living for centuries before they ever set foot on the shores of the American continent. Liberalism is tradition. The Anglo is liberal by birth. And America is an Anglo nation.

Long before John Locke or Adam Smith or any of the other foundational thinkers of modern liberalism ever put pen to paper, the English were:

An open, mobile, market-oriented and highly centralized nation, different not merely in degree but in kind from the peasantries of Eastern Europe and Asia…

[T]he majority of people in England from at least the thirteenth century were rampant individualists, highly mobile both geographically and socially, economically ‘rational,’ market-oriented and acquisitive, ego-centred in kinship and social life. Perhaps this is no surprise, for it would make them very like their descendants whom we are beginning to find out were like this three centuries later.

Those are the words of Professor Alan Macfarlane, in his remarkable 1978 book The Origins of English Individualism, a book whose implications are still, to my knowledge, to be fully appreciated by historians, social theorists, and political philosophers. But the importance of Anglo settlement and Anglo culture to the creation and the enduring shape of the American nation is well understood, or it should be.

What I’m saying is that if the American people want to recapture what was great about their nation—if they want to make America great again—then they will have to reckon with what made America what it was in the first place. And that was the Anglo and a way of life that was already at least half a millennium old in 1776.

We’ve come quite a distance from Tucker’s interview with Vladimir Putin, but the importance of the issue that it raises, our relationship to history—capital “H” and small—should be clear now, I hope. Putin believes that Russia is fighting for its very life, because it is fighting for its history and a nation is nothing without its history. We in the West, by contrast, believe we and our proxy Ukraine are also fighting for our lives, for the right to be free from history. Both can’t be right.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The war is a disaster in every sense.

The rise of the Wagner Group signals a significant change in power politics.

Gorbachev inherited an empire that was ready to dissolve.

Time is a weapon of war.

There is no moral equivalence between Ukraine and Russia, but neither country is Nazi Germany.