Adopting the opposition's words against them

Criminalizing Trivialities

Alvin Bragg’s indictment of Donald Trump abuses any definition of fraud.

Crimes like falsifying business records, forgery, filing false statements, impersonation, certain forms of obstruction of justice or of an official proceeding (such as by concealment, falsification, or false records), and conspiracies or rackets to do any of the foregoing are all instances of “fraud type” crimes. At their essence, they all require that there be a false statement or a misrepresentation—a lie.

Some crimes are frauds per se. These crimes are committed to deceive for some purpose, usually to obtain money or property. At the federal level, wire fraud, mail fraud, bank fraud, and health care fraud are quintessential examples of per se frauds. Prosecutors charge these per se frauds because obtaining money or property by deception is wrong in itself. But unscrupulous prosecutors can strain the wording and intended application of fraud statutes to bolster otherwise weak cases, obtain sentencing enhancements, or criminalize otherwise lawful conduct.

In the two federal indictments brought by Jack Smith, the Fulton County indictment brought by disgraced District Attorney Fani Willis and her lover Nathan Wade (now removed from the case for misconduct), and the indictment brought by Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, state and federal prosecutors have abused federal and state fraud-type criminal statutes. By my count, of the remaining 88 or so felony charges against Donald Trump, roughly 60 of them reveal egregious misuses of fraud-type criminal statutes. This essay analyzes the 34 counts in Bragg’s indictment, the trial of which is just underway .

What follows is not an analysis of the elements of the offenses charged against Donald Trump, which are often narrower than prudence dictates or legislatures intend. Rather, this essay explains how honest prosecutors use common sense to evaluate “fraud-type” cases, an evaluation that involves more than a mere hyper-technical application of facts to elements. When prosecutors deviate from this common-sense approach, cases get overcharged—sometimes egregiously so, as with Bragg’s indictment.

A Two-Axis Framework

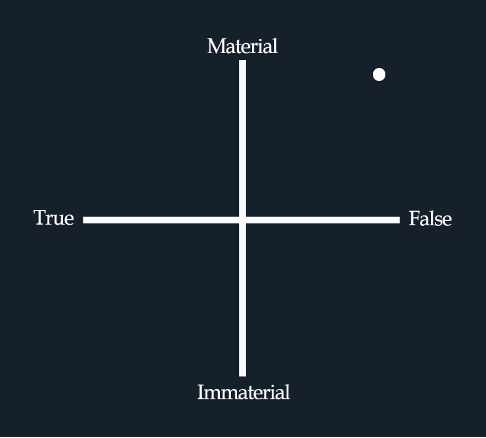

Prosecutors with experience investigating and trying fraud cases know that any statement or “representation” underlying an alleged fraud must be evaluated along two axes: a materiality axis and a true-false axis, as depicted in the simple graph below.

Common sense tells us that some statements lend themselves to a binary “true-false” categorization. They are either completely true or completely false. These statements include things like: “I was in Paris on the night of that murder,” or “I used the customer’s money to buy 100 shares of Facebook stock, as instructed.” Prosecutors love these types of statements because they can be verified easily and because they are unambiguous. If false, they can form the basis of a fantastic fraud prosecution.

Unlike those binary true-false statements, however, are statements that fall in the middle of the true-false axis. These statements don’t lend themselves to easy categorization. In everyday life, we tend not to think of these types of statements as either true or false, but rather as expressions of opinion or belief or, in contractual terms, “puffery.” For example, when a used car salesman assures you that a shiny new convertible “will be the best car you’ve ever owned,” he is expressing an opinion or “puffery.” If it later turns out that the old minivan isn’t the best car you’ve ever owned, you might be dissatisfied but you have not been defrauded.

The materiality axis is different. It exists to separate statements that matter from those that don’t, regardless of whether they are true. Case law defines a statement to be “material” if it “has a natural tendency to influence the decision of a person of ordinary prudence and comprehension.” There’s another concept in law called “reliance” which is distinct from “materiality.” In practice, however, they tend to run into one another. If, for instance, a buyer relies on a statement in making a purchase decision, the statement is usually considered “material.” If the car salesman told you that a vehicle had a 3.5 liter V6 engine and four-wheel drive, you would rely on those statements in buying the vehicle. This would make them “material.”

Prosecutors rarely prosecute fraud cases unless the underlying statements fall into the upper right quadrant of the chart above. They seek cases in which the underlying statements are both falsifiable and material. Keep in mind that whether the prosecution can actually prove that a statement is false is a separate question from whether the statement is, in principle, falsifiable. Prosecutors prefer that statements be material and falsifiable and that they have evidence to prove both. If a prosecutor lacks even one of these three components, the case is a dud. In short, fraud prosecutors are using this two-axis framework whether they know it or not. Honest prosecutors drop cases that aren’t at or near that nice white dot.

Lastly, though not every fraud-type crime includes materiality as an explicit element, prosecutors don’t prosecute trivial lies. Or at least they didn’t until last year.

The “Hush Money” Case

In April 2023, Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg brought a criminal indictment against Donald Trump. The indictment consists of 34 felony counts of falsifying business records in the first degree. Falsifying business records is a fraud-type case that an honest prosecutor would evaluate using the two-axis framework depicted above. As such, Bragg should be able to prove that Trump’s alleged statements were both false and material, even though the offense does not contain an explicit materiality requirement. In other words, through trivial misstatements can satisfy a hyper-technical reading of the offense, experienced prosecutors chalk that up to legislative oversight. They don’t treat it as a mandate to charge citizens with felonies for trivial lies.

Not Alvin Bragg. Bragg transformed a matter private to Trump’s business concerns into a public-interest false statement case, rebranded as a “hush money” case. Briefly, here are the facts: In 2016, Donald Trump caused $130,000 to be paid to Stormy Daniels to keep quiet about her alleged affair with Trump. Trump didn’t want to pay Stormy directly, so he asked his lawyer Michael Cohen to do it. Cohen agreed, paying Stormy’s lawyer Michael Avenatti on October 27, 2016.

To pay Cohen for his time and effort (and to reimburse him $130,000), Trump caused his business to make 12 monthly payments to Cohen of $35,000 each. These payments took place in each month of 2017. In the books and records of Trump’s business, these monthly payments were classified as “legal expenses” for accounting purposes. In the ledger, they were described as “retainer” or as “payment for services rendered.” Other similar entries were made.

To say that these “false statements” do not fare well in our two-axis framework is a gross understatement. They are borderline non-falsifiable and entirely immaterial. Take the statement “payment for services rendered.” Bragg calls this statement “false” and has built at least 12 felony counts of the indictment around it, one for each monthly payment to Cohen in 2017. But what exactly is “false” about it? What was it that Cohen was doing if not rendering services?

As for materiality, keep in mind that Trump owned the entities that made these payments. They were not public companies subject to SEC oversight. The statements in Trump’s books and records were not used to deceive investors, lenders, or third parties. They were entirely internal records kept and maintained by and for Trump. In short, Bragg is prosecuting Trump for “lying” to himself. This does not pass the materiality threshold that honest prosecutors require even in cases that lack it as a formal element. Put another way, this is not how the legislature intended this criminal statute to be used.

There’s another aspect of Bragg’s case that is alarming. Falsifying business records is ordinarily a misdemeanor, but it is enhanced to a felony if it’s done “with an intent to commit another crime.” Bragg dutifully made these bonus allegations for the purpose of enhancing all 34 misdemeanors to felonies. As I mentioned at the beginning, we should be suspicious of prosecutors enhancing fraud charges by trying to tie them to underlying crimes when those underlying crimes are not also charged. In this case, it appears Bragg believed Trump or Cohen committed a campaign finance violation. But Bragg never charged anybody with campaign finance violations. While it’s true that Cohen pleaded to two federal campaign finance violations, that shouldn’t be the basis of Bragg’s allegations because it was Trump who ultimately paid the bill, not Cohen. Indeed, the allegations include this furtive sounding bit: “Before making the payment, [Cohen] confirmed with [Trump] that [Trump] would pay him back.” And Trump did pay him back, roughly three times as much as Cohen paid Stormy. Some campaign contribution!

This has become known as the “hush money” case, which is weird since it is not unlawful to pay hush-money, though it can be unlawful to demand it. Indeed, every day in the United States, defendants agree to pay money to plaintiffs in exchange for their silence about alleged wrongdoing. We call these “settlements.” Trump’s attempt to “conceal” Stormy’s allegations of a sexual affair with Trump is even less serious than those litigation settlements because she suffered no damages. Since she suffered no damages, the only thing she and Avenatti were doing was threatening to “expose a secret or publicize an asserted fact, whether true or false, tending to subject some person to hatred, contempt or ridicule.” To that end, Bragg’s statement of facts does reveal an actual crime: the threat by Avenatti and Daniels to release the latter’s sex story prior to the election unless Trump paid them $130,000. Now that is a crime in New York—it’s called extortion.

At any rate, Americans have a solid, intuitive grasp of the two-axis framework described above, even if they’ve never thought about it explicitly. They know that the 34 counts in Bragg’s indictment are not legitimate allegations of fraud since they fail our two-axis test. They also know that Bragg’s enhancement of misdemeanor offenses to felony charges through clever lawyering reeks. Similarly, as I wrote in “Show Trial, American Style,” it is that intuitive grasp that explains part of the reason why 80,000,000 Americans also have grave concerns about at least two of the other indictments against Donald Trump, which consist mostly of over-charged, fraud-type crimes.

If inane trivialities like the words on ledger entries on Trump’s private books and records can now serve as the basis of criminal fraud charges, anything can.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Too often, experts who are working to "save American democracy" are doing anything but.

A government agency seeks to delegitimize conservative politics.

The former president retains a deep, intuitive bond with the national base.

Conservatives need to be a lot savvier about how they vet judicial candidates.

Yes, a Don/Ron brawl is inevitable.