Uncompromising discipline on crime is a must to merit the Republican nomination.

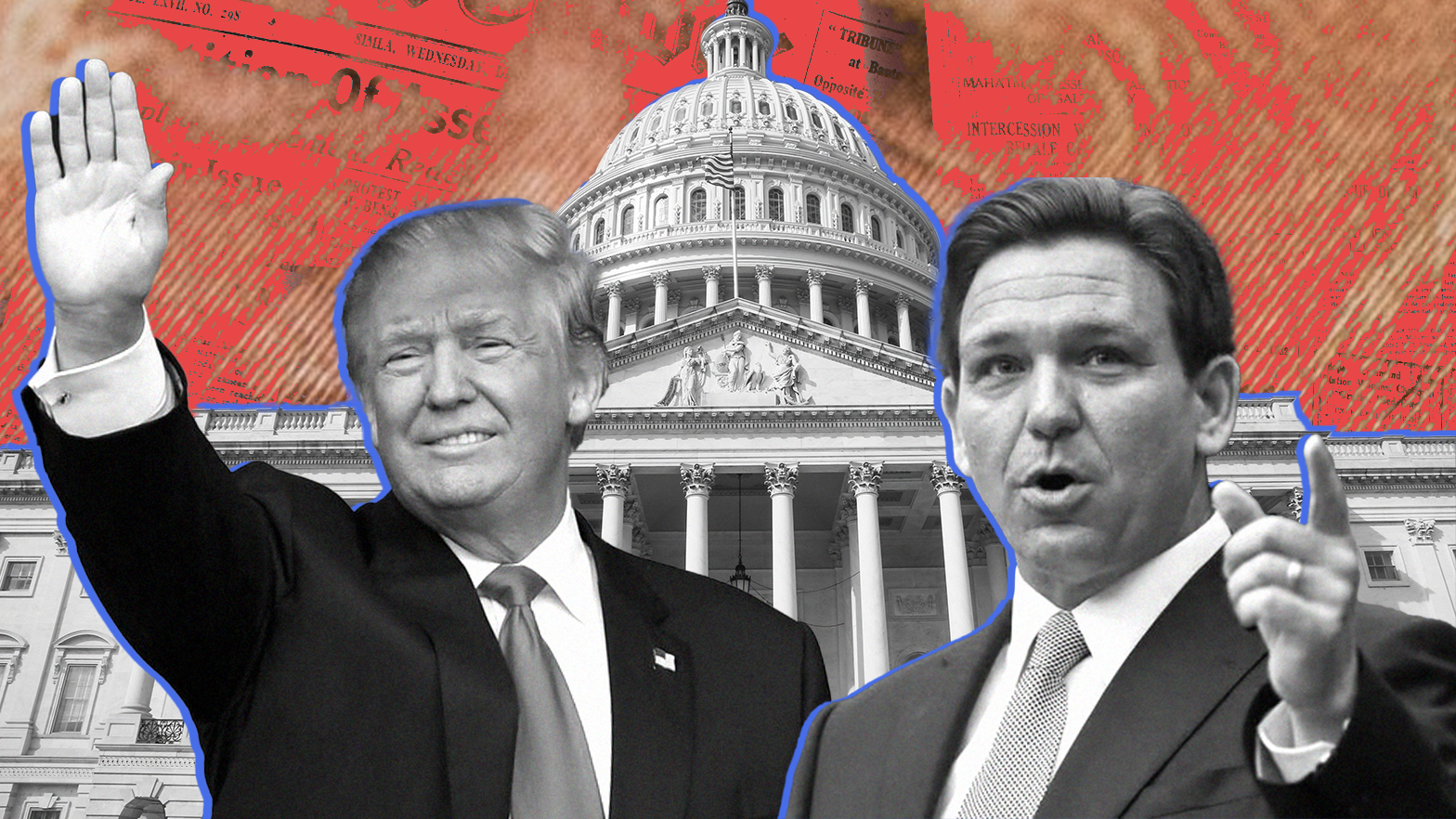

Trump Can Win

Odds are that 2024 will look a lot more like 2016 than 2020.

The final RealClearPolitics polling average for the 2016 race showed Hillary Clinton beating Donald Trump by 3.2 points. As of May 1, 2023, the same polling average shows Trump ahead of Joe Biden by 1 point.

Of course, Trump can’t win. Any Republican would do better. Every pundit says so. And when have they ever been wrong?

Trump didn’t enter the 2016 race until June 2015, so a direct comparison between his current polling numbers and those of the last cycle isn’t possible. But those who remember the 2016 race will remember that for most of the cycle, Trump trailed Clinton by rather more than the 3.2 points—as shown in the final RCP average. And of course, Trump won. The press underestimated his appeal.

Even in 2020, Trump significantly outperformed his polling. The final RCP average in that race showed a 7.2 point lead for Biden. His actual lead wound up being 4.5 points.

If not for all the experts saying otherwise, one would think that Trump has an excellent chance of winning the 2024 election. If the polls now are as far off as they were in 2016 and 2020, Trump will win.

But what about last year’s midterms? Didn’t they prove that Trump is a spent force?

Conservatives would have to be extremely stupid not to notice that, long before Trump came along, the Republican establishment and the mainstream media had a consensus about how to interpret elections.

Any time a right-wing candidate lost, it was always proof that the Right was unelectable and that candidate was a millstone around the Republican Party’s neck. But any time an establishment candidate lost—like John McCain in 2008 and Mitt Romney in 2012—nobody argued the party was too centrist or that establishment candidates were lead balloons.

When conservatives lost, it meant conservatives were losers. But when less conservative candidates lost, it was not a sign that less conservative candidates were losers. On the contrary: the reliable diagnosis from mainstream pundits and DC professionals was that the establishment Republican’s fatal vulnerability was whatever smidgen of conservatism might have crept into his campaign. The establishment, the dead center, was never to blame.

Conservative Republicans who noticed how that worked before the Trump era should recognize that a very similar pattern obtains today. The only difference is that now the liberal pundits and DC campaign consultants are joined by the professional conservative media in applying the same storyline to Trump.

When a Trump-endorsed candidate loses, Trump is to blame. When an impressionistically Trump-like candidate who isn’t endorsed by Trump loses, Trump is to blame. But when a non-Trumpian candidate loses, the lesson is never that non-Trumpian Republicans have an electability problem.

When a Republican who feuds with Trump, like Georgia Governor Brian Kemp, wins a smashing re-election victory, it’s a repudiation of Trump. But when a politician who was built up by Trump and is running in a wildly pro-Trump state wins a massive re-election victory, as Ron DeSantis did in Florida, the victory is in no way to Trump’s credit.

The narrative, in both its old anti-conservative form and its new anti-Trump one, is designed to steer voters. But it also has the effect of duping its own creators. Hence their surprise when Trump beat Clinton, and their dismay that Trump seems to be well-positioned to win the Republican nomination next year. They still, however, cling to the belief that he cannot win in November 2024.

Back From the Brink

Certainly the commentariat believes that any Republican could do better than Trump—so why risk the election on him? Until recently most polls have shown Ron DeSantis performing better than Trump against Biden. And some polls have even indicated that a generic Republican would do better than Trump. The Republican Party may be poised for presidential victory next year, but if it is, that’s despite Trump, not because of him.

The argument is superficially plausible, but it doesn’t take into account the demonization that will greet any Republican who gets the party’s presidential nomination. If another candidate starts off with higher positives than Trump, there’s no guarantee that by the time the media is done with him he won’t be seen in a much uglier light. With Trump, the media has already done everything that it possibly can do to make him look like the worst thing on two legs since Adolf Hitler. What more harm can they inflict upon Trump than they already have? But there’s plenty more they can inflict on anyone else.

Then there is the testimony of history. The last non-Trump Republican to win the White House was, of course, George W. Bush. In 2004 he had every advantage: he was the incumbent, Reaganite enough to thrill movement conservatives yet “compassionate” enough to reassure centrists of both parties. The conservative movement was unified behind him (he had no primary challenger, and the few conservatives who dissented from the Iraq War at the time were tarred as disloyal to party and country). The War on Terror was still popular, and same-sex marriage was on several states’ ballots to drive turnout for “values voters.”

With all that going for him, the best George W. Bush could manage was 286 electoral votes. Not since 1916 had any re-elected incumbent fallen short of 300 votes in the Electoral College.

Even Karl Rove should have been able to recognize what that anemic number meant. The 2000s Republican electoral coalition, under perfect conditions, had no margin to spare. If the rising unpopularity of the Iraq War or the rising acceptance of same-sex marriage shifted the electorate even a little, or if there was a recession, or a Republican scandal, or simply a more charismatic Democratic nominee than John Kerry, that 17-vote margin that re-elected Bush would disappear.

2004 represented the ceiling of what the pre-Trump Republican brand could achieve. Even at the time, the ceiling was caving in and would soon collapse completely, thanks in large part to Bush’s foreign policy and the normalizing of same-sex marriage.

The Republican Party would not be better off if the Trump revolution had never happened. In 2016, Trump smashed through Bush’s electoral total with 304 votes. He did it with a more provocative personality than Bush, a different policy mix (in particular on foreign policy, trade, and immigration, where Trump’s views were closer to Pat Buchanan than to Bush’s), and a campaign that brought the candidate to Rust Belt districts long neglected by nominees from both parties. If Trump’s personal controversies were as much of a detriment as common sense suggests, then the appeal of his campaign technique and issue positions must have been even greater than those 304 electoral votes attest.

Far from dooming the Republican Party, Trump saved it from the reputation that Bush and the conservative movement of his era had left it with. The party of 2004 could never win again. The ease with which Trump defeated the heirs to that party—Jeb Bush, but also Ted Cruz and the rest of the 2016 field—was a verdict on the very philosophy of the GOP as it stood between 1992 and 2012. As a set of principles, the philosophy of the GOP couldn’t even prevail in the party itself, let alone in the wider country.

Perhaps a post-Trump GOP brand will be more popular than either Trump or the party’s pre-Trump identity. But a truly post-Trump Right doesn’t yet exist—the present alternatives to Trump in the Republican Party are either variations on Trumpish populism or regressions to pre-Trump conservatism. I was at a dinner in DC recently where all the conservatives in the room, except me, agreed that the future of the GOP was Ronald Reagan. The closest thing to a post-Trump option that most DC intellectuals can imagine involves resorting to necromancy.

Lessons to Learn

So yes, Trump can win in 2024, and the fact that he still defines the party’s identity means he is overwhelmingly likely to be its nominee. Ron DeSantis does have a shot—he argues that he’s a more competent leader for the Trump-era Right than Trump himself is. But the Trump (and Biden) era doesn’t seem to be characterized by voters placing a premium on competence, and it’s hard to convince Republicans you’re to the right of Trump when Trump is the personal symbol of the Right today. In much the same way, Reagan was the symbol of the fusionist Right—and when did a more-Reaganite-than-Reagan candidate ever win anything through the purity of his principles?

Many of my Florida friends think that the way to win Wisconsin and Michigan in 2024 is to refight the COVID battles of 2020-21 and to talk about transgenderism more than anything else. But this approach is not so different from that of my DC friends who think the way to win the Rust Belt is to talk about slashing the federal bureaucracy and reining in the Federal Reserve. The issues are important in their own right—but that doesn’t mean they drive enough votes.

Trump, however, has to learn the lessons of his own success in 2016. One lesson is the importance of a figure like Steve Bannon—someone who can concentrate Trump’s attention and translate his themes into concrete imagery. This is what Bannon did with “the wall.” As a simple, easy-to-envision policy that acted upon a broad issue (immigration), “the wall” was something that voters could remember and refer back to. Contrast that with the incredibly lengthy lists of policies that Mitt Romney used to rattle off in 2012, which were not only beyond what most voters could remember but also failed to leave any vivid impressions.

A lesson that Trump clearly has learned from his own experience, both in 2016 and 2020, is that rallies and in-person campaigning are his strength. Four years ago Joe Biden could avoid the campaign trail with COVID as his rationale. In 2024, the contrast between a vigorous, rally-leading Trump and a president without the stamina or mental acuity for prolonged public events will be striking. The advantage that his rallies conferred on Trump in 2016 should be all the more pronounced next year.

Where Trump’s advantage will be less pronounced, if he still has an advantage at all, is in pitching himself as the candidate for the industrial workforce. Biden has always understood far better than Hillary Clinton ever did how to appeal to traditional labor constituencies, and he has used the power of the presidency to enhance that appeal. His personal affinity for the state of Pennsylvania also gives Biden an edge that Clinton lacked. Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania can make or break either campaign. But working-class voters don’t just want jobs or federal dollars. They also want respect. They want to feel like they’re part of a winning team called America again. Can Trump restore their confidence and win it for himself, better than Biden can, even with the largesse the incumbent can dole out? He has to try.

The failures of 2020 should also be instructive: for instance, they show that Republicans have to take non-traditional get-out-the-vote efforts far more seriously, including by running GOP campaigns for early and mail-in voting. There are principled reasons why moving away from voting in particular places on a particular day is detrimental to American democracy. Turning voting into an ongoing plebiscite is bad in absolute terms, quite apart from the risk of fraud or other forms of mischief. But the midst of an election is the wrong time to worry your own voters about the voting system. Republicans should find it just as easy as Democrats to vote early or by mail—just as easy in practice and just as psychologically easy. Otherwise, the Democrats will enjoy a field left to themselves.

Another 2020 mistake that Trump will have to avoid is being ill-prepared for the debates and investing too much in trying to embarrass Biden with the shameful lifestyle of his son Hunter. While the Biden family’s corruption is a valid issue, Trump struck too many voters as a bully picking on an old man and his troubled son—whose condition strikes many Americans in the age of opioids as painfully relatable. Trump may or may not win the debates, but he cannot afford to look as bad as he did in the last cycle’s head-to-head meetings.

Trump is inclined to talk endlessly about his own legal problems and the degree of persecution to which he feels subjected. This may or may not be a turn-off to persuadable voters—it runs the risk of reminding some of them just how many suits and investigations Trump has faced, and how much they distracted from the nation’s business. The other hazard that a preoccupation with his legal cases presents, however, is that it subtracts from the time and energy available to talk about how voters and their families feel about their own circumstances. When Trump says that his enemies go after him to get at “you,” his message has power. But he has to be mindful about connecting his woes with other Americans’.

Picking a Second

Going into 2024, Trump has more flexibility in one respect than he had the last time he took on Biden. He can now choose a new running mate. Pence made sense in 2016, when Trump needed to reassure conventional Republicans, especially religious ones, that his ticket would be good for them. In 2024 the most valuable assistance a running mate might contribute would be the chance of winning a state that otherwise would go to Biden.

Virginia, where Governor Glenn Youngkin currently enjoys an approval rating in the mid-50s, might be a prospect. Trump lost Virginia in 2020 with 1.96 million votes to Biden’s 2.4 million. Interestingly, however, in 2012 Barack Obama won the state with 1.97 million votes, and in 2016 Hillary Clinton won it with 1.98 million. In most years, Trump’s 2020 Virginia total would be a winning number, or close to it. Is it possible that Trump’s Virginia voters are more enthusiastic than they were in 2020 and Biden’s are less motivated? That Youngkin as a running mate could tip the state into the Republican column?

If not, there could still be advantages in forcing Biden to spend time and money on what might otherwise be a safe state, and Youngkin—former CEO of the Carlyle Group—might be reassuring to corporate class Republicans around the country who are alienated by Trump and populism.

Several other possible running mates, such as Senator Tim Scott, also have the potential to be useful for outreach. But Scott would also leave ideologically focused populists cold. What may work well for the math at the ballot box may prove a source of conflict in a second Trump Administration, if the vice president’s staff are not loyal to the president and his agenda. Reagan thought he had good reason to partner with George H.W. Bush in 1980. But when Bush succeeded Reagan, he fired almost everyone who had supported Reagan over himself in the 1980 primaries. The GOP’s disastrous turn to neoconservatism began with that betrayal. Electoral math can’t be the only criterion in choosing a running mate. But a pick that widens the Trump coalition will help to avoid making 2024 a replay of 2020, even if it is a rematch.

The New Trump Moment

Immigration is an even hotter issue than it was in Trump’s last two elections. President Biden has been impaled on the horns of a dilemma here. When he delivers the porous-borders policies his base expects, the results are so chaotic that a political backlash is inevitable. But when Biden tries to forestall the backlash by restoring some immigration enforcement, he winds up accused by the Left of doing exactly what Trump would do. This is a winning issue for Trump, and when the media attacks him for it, he should be prepared to point to Biden’s own half-hearted acceptance of enforcement. Even Biden knows that something has to be done and liberal policies have failed. On immigration, Biden himself makes the case for Trump.

Foreign policy also plays even better for Trump in 2024 than it did in 2016. The message is simple—Biden humiliated America in Afghanistan and has no plan to end the war in Ukraine swiftly or successfully. The war in Afghanistan went on too long and ended badly because the foreign-policy establishment pursued unrealistic aims and had no finite gameplan. The war in Ukraine is going the same way, sucking unlimited resources out of America and our allies on an open-ended timetable. The Biden Administration and bipartisan foreign-policy elite once again define victory only in the vaguest and most idealistic terms. The same means in pursuit of the same obscure end will produce in Ukraine the same results as in Afghanistan. Trump offers the only alternative.

The fundamental forces that helped to elect Trump in 2016 are more compelling than ever. America’s leadership class is unpatriotic and incompetent. It unsuccessfully tries to provide security for Afghanistan and Ukraine even as it fails to police our own cities and borders. Biden and the rest of the elite are more interested in ruling the world than re-establishing the rule of law at home. Americans have suffered the consequences. Trump may be imperfect, but voters have now seen what happens when the country reverts to a pre-Trump leader like Biden. The political class has not mended its ways. It has to be replaced, and Trump is the beginning of its replacement.

Trump is polling well enough already that he can be cautiously confident about next year. There’s a danger that he and DeSantis will drive up one another’s negatives to the point where either of them would have a much tougher time taking on Biden next November. But if that doesn’t happen, the odds are that 2024 will look more like 2016 than 2020.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

And rightly so.

A time for unreasonable expectations and irrational politics.

The 2022 midterms were a blessing in disguise for the GOP.

Donald Trump, the GOP, and 2024.

Whoever wins in 2024, our problems run deeper.