Uncompromising discipline on crime is a must to merit the Republican nomination.

Monster Slayers (Still) Needed

We love not the ancient but the good.

Today, I would contend, we honor our founding fathers best not so much by following their rules for constitutional government, but by appropriately imitating their revolutionary boldness. Do any Republican politicians today agree with that idea, or even understand it?

The Declaration of Independence acknowledges that people “are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.” Yet they also have a moral duty to defend their rights when “a long train of abuses and usurpations” reveals “a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism.” Even the sober Federalist claims that the United States represents an unprecedented experiment, testing “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice.” Do we not betray that trust when we assume that the framers, having invoked their deliberative freedom, forever eliminated the need for us to exercise our reflection and choice?

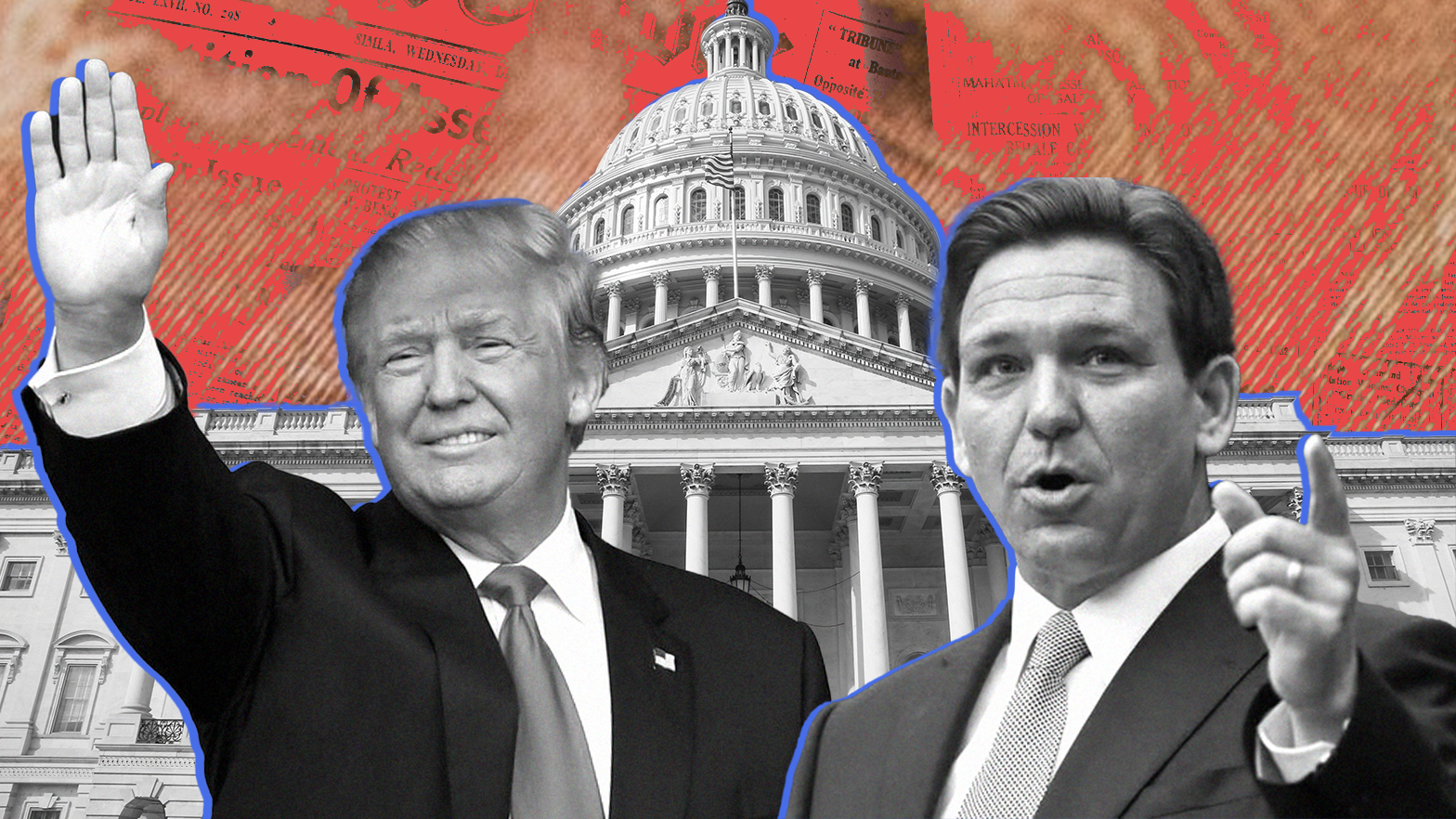

I argued in January that we “need to be unconventional in thinking about what’s necessary in this post-normal, post-constitutional regime. We can’t judge either Trump or DeSantis, or any other contender who may emerge, according to the old standards.” We are in desperate need of a statesman who combines the determination and practical effectiveness of DeSantis with Trump’s weird political genius and authentic concern for the sovereign American people. Such a statesman would have to implement—and explain—an agenda ruthlessly assailing the bureaucratic ideology of the ruling class while pursuing the founders’ goal of protecting our equal, natural rights.

America is now so dominated by what Charles Kesler calls our “second Constitution” that a simplistic adherence to the older institutions and practices simply isn’t sufficient anymore. Every month, more evidence piles up confirming that the juggernaut of left-wing fanaticism will never stop—whether it’s punishing homebuyers with good credit scores, allowing the border to disintegrate further with the expiration of Title 42, or blessing the growing anarcho-tyranny in our cities with lenient sentencing for disturbers of the peace and harsh penalties for those who undertake to restore it. Among the grievances Jefferson included in the Declaration was Britain’s disdain toward the colonists’ complaints: “Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury.”

Republican strategists and office-holders, as well as intellectuals on the Right, need to do a much better job of letting go of conservativism as a mindset, and focusing more on our aims, which must include overturning much of the status quo. The Right has always been good about understanding that human nature doesn’t change, and neither do the principles of justice. But circumstances do change.

The Democrats, of course, never have a problem recognizing that new conditions require new approaches. We can see this in their skilled and unskilled operatives alike. Barack Obama is by all estimates a vastly better politician than Joe Biden, especially in his rhetoric (or what we nowadays call messaging). Obama’s “Hope and Change” campaign slogan eloquently captured the open-ended, somewhat utopian liberal attitude toward government. There was no need for him to explain what we were supposed to hope for, or what kind of change the country needed. The future, according to liberalism’s default attitude, is always better than the past, and change is always desirable for its own sake. By contrast, Biden’s election motto in 2020 was as forgettable as the rest of his campaign—so forgettable, in fact, that I had to look it up: “Our Best Days Still Lie Ahead.”

As limp as Biden’s slogan was, it still hewed to the leftist dogma of historical progress. Trump’s signature line, “Make America Great Again,” was more confident about the past than the future. Like so much about Trump, there was a certain mysterious brilliance at work in that slogan. Given Trump’s penchant for speaking off the cuff and sticking to his own peculiar style, it seems likely that if he didn’t invent that phrase, he did approve it personally. The motto recognizes that America was once admirable but has now fallen onto hard times, and only by our own effort can we understand and recover what made it noble and worthy of sacrifice. Abraham Lincoln noted that we are not the “iron men” our fathers were, and that our “republican robe is soiled, and trailed in the dust.” He urged us to repurify it “in the spirit, if not the blood, of the Revolution.” Trump’s slogan is only a pale reflection of Lincoln’s oratory, yet it reflects a similar circumspection: no guarantee of success is implied, only an imperative or exhortation.

Largely because working-class voters are experiencing the hard times firsthand, while the Beltway elites remain comparatively secure and comfortable, the Republican base understands better than most of the party leadership that America is no longer great. The Complacent Conservatives aren’t much alarmed by that persistent grinding noise coming from the engine room, because on the upper decks the sun is shining and the drinks are flowing. They can’t really understand why anyone would question the continuing efficacy of the founders’ framework. They see the ship of state running, if not perfectly, then at least adequately. They definitely can’t understand the demand for revolutionary change, and some are even appalled at the idea. There is a certain irony in this blindness.

Our first Progressive president, Woodrow Wilson, argued that the “makers of our Federal Constitution… were scientists in their way.”

And they constructed a government as they would have constructed an orrery [a mechanical model of the planets],—to display the laws of nature. Politics in their thought was a variety of mechanics. The Constitution was founded on the law of gravitation. The government was to exist and move by virtue of the efficacy of “checks and balances.”

For all their criticisms of the Progressives, some conservative intellectuals risk becoming the caricature Wilson derides. They simply can’t get their minds around the idea that the founders’ mechanisms could ever stop working. But Wilson’s new theory of government is no abstract threat; it has now become (in large measure) the current practice.

The Progressives’ theoretical and practical success reminds us that political philosophy is always relevant—a lesson the Claremont Institute was created, in part, to demonstrate. Plato, as it turns out, has something important to teach us. In a dialogue called Euthyphro, Socrates is shown examining the nature of piety: what do we owe to the gods? We learn that Socrates is unsatisfied with the traditional teaching that the Olympian gods quarrel among themselves, for this would show that they don’t know the Good. One of the questions that comes up is whether we should simply obey whatever edicts the gods hand down, or whether we should imitate the gods, by seeking out and honoring what is righteous and holy in and of itself. The dialogue does not supply a clear answer, but it points toward a conclusion offered elsewhere by Plato’s student, Aristotle: “We love not the ancient, but the good.”

Likewise, let us consider whether we should revere the founders by seeking what is good for America—drawing on their wisdom as much possible, but finally imitating them in their spirited love of liberty, not merely in their precepts. The ultimate objective for any Republican presidential aspirant today must be revolutionary: to recover our equal, natural rights and the moral conditions of freedom, “as prudence indeed will dictate.”

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

And rightly so.

A time for unreasonable expectations and irrational politics.

The 2022 midterms were a blessing in disguise for the GOP.

Donald Trump, the GOP, and 2024.

Whoever wins in 2024, our problems run deeper.