Not in America, and not anywhere else.

The Risks of American Populism

Liberalism, pluralism, and self-government are indeed under threat.

Although Colin Dueck and I represent different points on the ideological spectrum, I find myself in agreement with him on several key points. The rise of what he terms a “conservative-leaning populist nationalism” is perhaps the most important development of the 21st century, at least among the world’s democracies. It determined the outcome of the Brexit referendum in the U.K. and the 2016 U.S. presidential election. It has catalyzed the establishment and growth of national populist parties throughout most of Europe. Leaders such as Turkey’s Erdogan, India’s Modi, the Philippines’ Duterte, and Brazil’s Bolsonaro have carried this creed far beyond the confines of the West. It represents a fundamental challenge to the liberal democratic international order that has dominated the globe since the fall of the Berlin Wall and collapse of the Soviet Union.

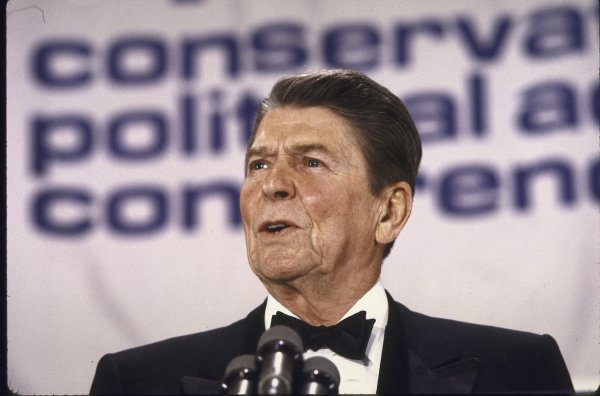

I also agree with Dueck on the centrality of cultural issues in the rise of populist nationalism. In the United States, official conservative opposition to New Deal liberalism ended in 1952 with the victory of Dwight Eisenhower’s “modern Republicanism” over the flinty economics of Senator Robert Taft. Less than two decades later, Richard Nixon declared that “we are all Keynesians now.” Not even Ronald Reagan dared to tamper with Social Security, a program established by the president for whom he voted four times.

To be sure, the rise of supply-side economics and concerns about federal spending and regulations sustained the economic dimension as an axis of division between the parties. But the rise of Donald Trump muted—or mooted—many of these issues. During his announcement speech, the future president pledged to protect Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid against cuts, and his administration’s fiscal policy bespeaks a vast indifference to the deficit concerns that drove former House Speaker Paul Ryan. Indeed, Mr. Trump’s combination of spending increases and tax cuts, which has boosted consumption without enhancing investment, represents a Keynesian stimulus on steroids. All the while, he rallies his core supporters with promises to build a wall against what he terms an invasion from the south and to use all the tools of immigration policy to exclude Muslim newcomers from our country.

Brexit might well have lost had these claims proved decisive. Non-economic concerns—immigration, rapid change in local communities, and national sovereignty—put Brexit over the top. In Europe, cultural anxieties rose after the migrant surge of 2015, propelling parties such as Italy’s Lega from marginality to central forces in their countries’ politics.

I agree, finally, that it would be a mistake for those who are troubled by the rise of populist nationalism to dismiss the widespread concerns it reflects. The transformative effects of immigration, the central role of the judiciary in cultural change, and the rising power of international institutions are open to legitimate contestation on grounds that are anything but anti-democratic, let alone deplorable.

It’s the Economy—Still

This said, I must take issue with Dueck on two points. First, the focus on cultural issues should not come at the expense of recognizing the important role of economic change in the rise of populist nationalism. The erosion of manufacturing economies in the West that began in the 1980s put pressure on working-class jobs and wages, while the rise of post-industrial, information-based sectors enhanced the well-being and status of educated professionals. Established center-left political parties deemphasized their traditional focus on working-class issues in favor of upscale professionals’ concerns, decoupling working-class voters from the Left and opening them to conservative appeals. Candidate Trump’s repeated promises to reopen shuttered factories and bring back manufacturing jobs reflected this shift in the composition of the conservative coalition, while the increasing identification of the professional classes with the Left established education as a key dividing line between progressives and conservatives.

These opposed trends of manufacturing decline and information-sector growth also had geographical consequences that have reshaped electoral politics. In the post-war decades, manufacturing tended to narrow gaps, not alone between classes, but also among regions. The rise of information economies has had the opposite effect. Throughout the United States, the U.K., and Europe, metropolitan areas have moved ahead while smaller towns and rural areas have lost population and economic dynamism. Many residents of non-metropolitan areas feel that they have been left behind, and they resent it, opening the door to populists who rally the peripheries against the center.

Populism’s Shadow

My second disagreement with Dueck goes to the heart of contemporary anxieties about the future of liberal democracy. While it is true, as he says, that populism is not necessarily authoritarian, it leans against the institutions and social realities of contemporary liberal orders. Populists typically incline toward unfettered majoritarianism and are impatient with limits on pure majority rule such as individual rights, independent judiciaries, and constitutional forms. In practice, populist parties and movements are led by strong charismatic leaders who claim to be able to fix the ills of their societies by bringing the power of the people to bear on anyone and anything that impedes their will. Concern over President Trump’s view of executive power as unlimited, his willingness to bypass laws passed by Congress, and his dismissive attitude toward judges who refuse to bend to his will is more than partisan.

Moreover, populists typically distinguish between the “real” people and the others, who don’t count, a distinction that often reflects racial, ethnic, and religious differences. In the United States, many grassroots populists believe that you can’t be a full and genuine American unless you are a white Christian of European ancestry who was born in the United States. While contemporary liberal democracies are increasingly diverse and pluralistic, populists tend to be anti-pluralist, resisting diversity in the name of a lost and partly mythical homogeneity that cannot be restored. Whatever some may want, Latinos will not leave the United States any more than Pakistani shopkeepers will leave the U.K. or Turks leave Germany.

Dueck recognizes—but understates—the stresses in the Republican coalition that the Trump-led populist takeover has produced, and not just on economic issues. While many business-oriented conservatives favor the Trump administration’s tax cuts and regulatory roll-back, they are opposed to President Trump’s policies on immigration, trade, and international institutions and to his stances on social issues, which they see as divisive and bad for business. Suburban-based Republican moderates, appalled by his rough-and-tumble tactics and his treatment of women, are deserting in droves. The hope of populist theoreticians is that conservative parties can embrace the populist agenda without losing ground among their traditional supporters, but every US election since November 2016 has challenged this hope.

The populist explosion will not leave the political establishment unchanged, nor should it. But in the long run, parties from the center-right to the center-left can assimilate what is valid about nationalism and populism without yielding to forces that would weaken liberal-democratic protections for individual freedom, social diversity, and self-government under the rule of law.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

America’s future turns on an iron hinge.

Working citizens rightly rally around statesmanship, not ideology.

The new movement in American politics is unlikely to disappear anytime soon.