Restorative reproductive medicine should be the MAHA response to infertility.

IVF Is Not the Answer to the Fertility Crisis

Our current birth dearth will not be solved by assisted reproductive technologies.

One year ago, President Trump signed an executive order directing his administration to develop policy recommendations to protect access to in vitro fertilization (IVF), expand its availability, and lower its cost to patients. Then in October, the administration announced additional measures to lower costs for IVF and common fertility drugs and explore pathways like expanded employer benefits or excepted benefit categories for assisted reproductive technologies. While this included joint efforts across federal agencies to make this costly intervention more affordable, the administration stopped short of imposing broad new federal mandates for insurance coverage or direct government funding of IVF.

The problem of below-replacement fertility rates in the U.S.—which poses serious demographic, social, and economic challenges—has gained some political attention since the last election. As of 2024, the fertility rate in the U.S. stands at a record low of 1.6 births per woman of childbearing age, well below the replacement rate of 2.1. This drop continues a downward trend that began in the early 2000s and accelerated after the 2008 recession. Trump frames his support for IVF as a way for the government to support couples who desire to start or grow families. While this administration has not yet enacted universal “free” IVF, as initially floated in Trump’s campaign rhetoric, the policies show clear support for making IVF accessible to more Americans.

But the notion that expanding access to IVF will measurably alleviate our fertility crisis is pure fantasy. First, the goal of achieving a significant number of additional births using government-funded IVF will prove cost-prohibitive: the procedure typically runs $15,000 per cycle plus $5,000 for medications. Second, the success rates tend to be low: a typical IVF cycle achieves pregnancy in about 20-35% for women under 35, and this low number drops further with age.

IVF is usually employed for infertile women who have been unable to conceive naturally. But infertility, while far from a trivial issue, is not a significant driver of our low birth rates. A 2013 Gallup poll found that, on average, American adults want to have between two and three children, a statistic that has remained unchanged since the 1970s. The 5% of adults who do not want to have children had not changed much since 1990. The fact that many Americans are not realizing their desire for children is, for the most part, not a result of medical problems leading to infertility. The main source of our birth dearth is not biological but economic: more than three-quarters of those who want more children but do not have them cite financial considerations as the main reason.

The $20,000+ invested in each IVF cycle, only to achieve a 25%-30% success rate, would be better spent on other economic incentives to encourage family formation for those who believe they cannot afford children. We can and should argue over the details of specific policy proposals—be they child tax credits, support for stay-at-home moms, or other measures to stimulate the economy generally. But regardless of our favored policy solutions, there is no doubt that these kinds of proposals promise to deliver far more per dollar than IVF. If you want more babies, simply creating them in a petri dish will not do: we need to make it more affordable for Americans to raise these children after they are born.

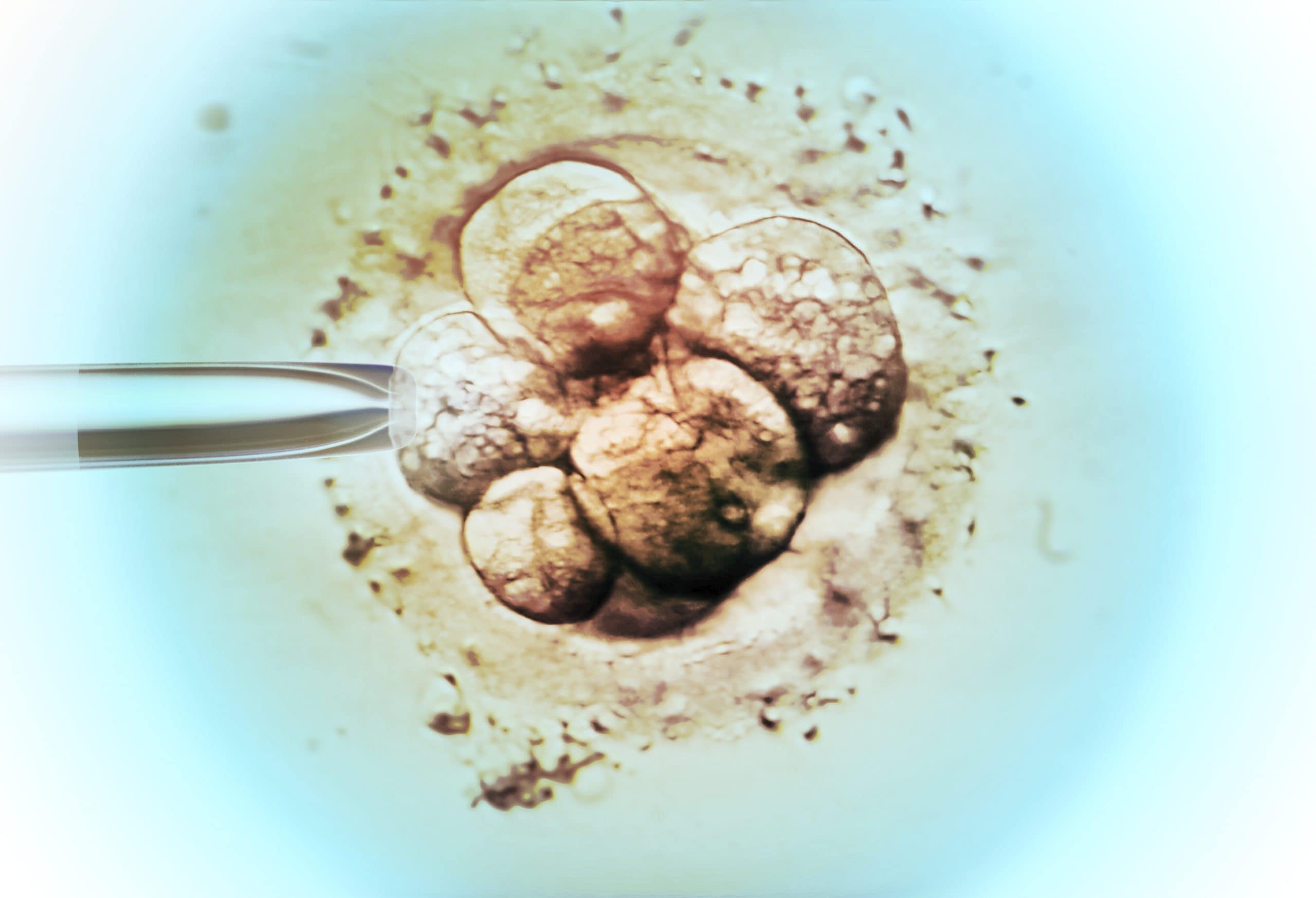

Even when it helps couples to have a child, IVF comes with serious ethical costs. Clinics compete in the market based on success rates. Because egg harvesting is an invasive and sometimes risky procedure, IVF cycles typically aim to create as many embryos as possible—usually more than the couple intends to bring to birth. Unused embryos go into frozen storage but can later be thawed and implanted. In one 2022 experiment, run by its very nature without consent, twins were born after 30 years in cold storage. Their adoptive father was five years old when they were first conceived.

It is not known precisely how many embryos are now in cryopreservation, because clinics are not required to report these numbers. Estimates range from 500,000 to millions. Many of these end up abandoned by parents who stop paying the $500-$1000 yearly storage fees and fail to respond to repeated outreach from clinics. Most parents remain reluctant to allow clinics to destroy their spare embryos, suggesting at least moral ambivalence. Other available options include adopting out embryos to another infertile couple or donating them to embryo-destructive research. Parents likewise rarely consent to these, likely out of similar moral reticence. These parents know well what happens when those “clumps of cells” are placed in a mother’s womb.

Thus, parents who do not want to raise additional children are stuck in an insoluble ethical conundrum; their embryos are left in a cryogenic nursery limbo. It’s hard to entirely blame IVF clients for this when all available choices seem morally problematic. Even when they are informed of these options before starting IVF, most couples admit that they were singularly focused on achieving a pregnancy and rarely considered what would happen to their excess embryos until they later faced the decision. In creating countless human embryos that will never be placed in a uterus—the only conducive environment for embryonic life—we have created a problem for which there is no morally just solution. This should invite us to reevaluate the practice that created this insoluble quandary in the first place.

It’s important to acknowledge the anguish of infertility for those couples trying unsuccessfully to conceive. However, there are better solutions to offer them than IVF. The egg-harvesting phase of IVF introduces nontrivial medical risks. Although we need much more longitudinal data on this, current evidence strongly suggests significant risks also for the child conceived by this procedure—including elevated risks for birth defects, as well as chronic illness later in life, such as cardiovascular problems and metabolic dysregulation, cognitive impairment, and perhaps even cancer, possibly due to epigenetic changes introduced by the procedure. This research supports the common-sense notion that, whenever possible, it would be preferable to make babies in the bedroom rather than the laboratory (and much more fun, as most couples will attest).

Nevertheless, the focus on IVF as the solution to infertility—and often the first solution offered to infertile couples—has dampened research and clinical efforts aimed at treating the underlying causes of infertility. Instead of focusing on IVF, the Trump Administration should support medical interventions that help previously infertile couples to conceive a child in the womb. As in many other areas of contemporary medicine, we reach immediately for medically invasive, lab-based procedures. We offer couples a Band-Aid—or in this case, a workaround—for the problem, instead of assessing and attempting to correct the underlying cause.

Interventions under the umbrella of restorative reproductive medicine range from dietary changes or hormone balancing to, in some cases, medications or surgery. This approach accords with the sensible and necessary push by the new administration to Make America Healthy Again by addressing the root causes of our epidemic of chronic illness, rather than just applying superficial, expensive, and suboptimal quick fixes.

There are several challenges to making these interventions available and accessible to more couples, which sensible policies can begin to address. Not only is research inadequately funded, but we also currently lack sufficient training for physicians in assessing and treating the root causes of infertility. To mention just one example, among the most common causes of infertility is endometriosis—a condition that not only makes it difficult or impossible for the affected woman to maintain a pregnancy but also, if uncorrected, causes intense pain and other troublesome symptoms. However, most physician specialists are not trained in the complex surgical approach required to adequately treat endometriosis to allow for pregnancy. Other such examples abound.

We should applaud the Trump Administration’s laudable goal of helping infertile couples to bear children. But IVF is not the right solution. Instead of putting all our eggs in one basket, we need a capacious approach to supporting fertility that does more to address the root causes of infertility and, whenever possible, restore reproductive function the way nature intended. This strategy respects human life at all stages and avoids insoluble ethical quandaries. It also offers a recipe for happier parents and healthier children. Surely this is a proposal for addressing our fertility crisis that all Americans can endorse.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

What the pro-life movement needs is clarity, not reactionism.

Natural law, IVF, and infertility.

Challenges and opportunities in a fraught domain.