Science makes faith plausible, not impossible.

The Secret Knowledge

An alternative to dystopia.

This essay is a companion piece to Andrew Klavan’s newest book, The Truth and Beauty. It is available for purchase here.

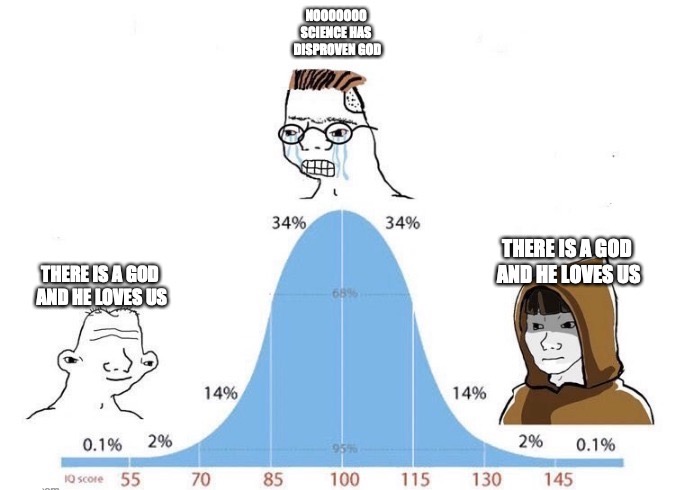

The recent internet Bell Curve Meme stuck with me long after its fleeting shelf life had passed. One end of the meme’s Bell Curve represents the small percentage of primitive idiots making some simplistic observation about the world. The peak of the curve represents the majority of intelligent thinkers describing the same phenomenon with analytic subtlety, scientific precision and moral nuance. The far end of the curve represents the small percentage of Jedi-like sages who, of course, describe the world in the same simple terms as the idiots.

Therein lies the heart of what I have come to call the Secret Knowledge. Indeed, it is secret not because no one knows it, but precisely because intellectuals are loath to speak its wisdom aloud for fear of sounding like the idiots and thus losing their claim to modern legitimacy.

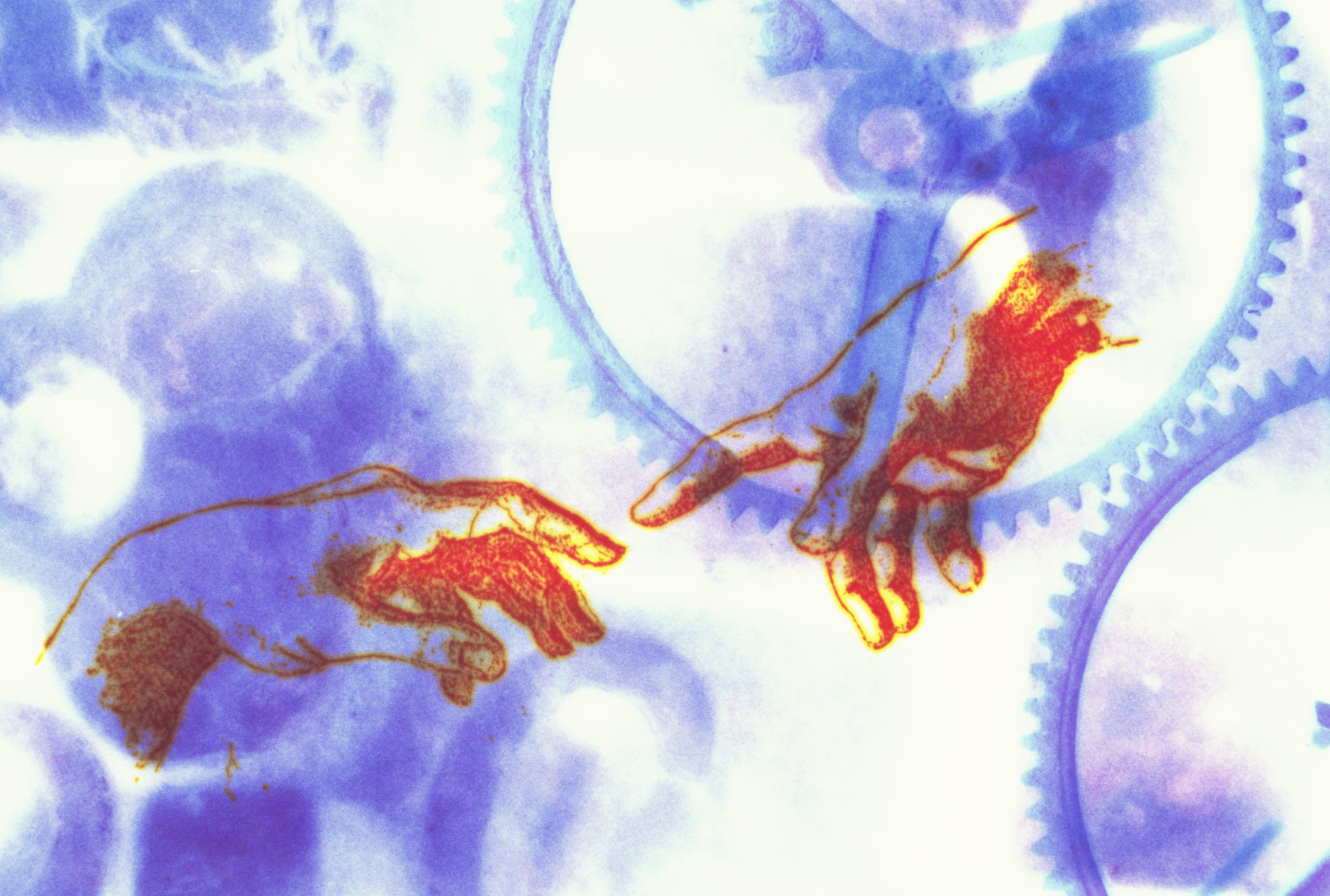

The Secret Knowledge is merely this: there’s a God, creation speaks his nature in the language of matter, and only in guileless surrender to that Word made flesh can we enter eternity and become fully human. The Bell Curve Meme tells the tale: we have to grow very wise before we can embrace such simplicity. Or to put it in something like its original form, unless we become like little children again, we cannot enter the kingdom of heaven.

No cool kid wants to spout such stuff. Yet, as fearful as we are of ceasing to be hip—or whatever word has now become the hip replacement—it is clear and becoming clearer by the day that the alternative to the Secret Knowledge is surrender to a soul-withering dystopia, an earthly analogue of hell.

I recently noticed something rather odd about such dystopias. I was thinking of the classics of the dystopian genre: Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), which set the standard; Lois Lowry’s The Giver (1993), which has filled the young adult shelves with imitators; or the film The Matrix (1999), which Mark Zuckerberg has now sworn to bring more or less to life as the Metaverse. What’s odd about them is this: In each of these works, the majority of the characters who inhabit the nightmare, do not find them nightmarish at all.

The denizens of Huxley’s brave new world may be genetically engineered and socially conditioned to fulfill the roles of their social classes; they may be amused by meaningless sexual encounters and cheered and pacified by the drug SOMA, but they are, almost by tautology, very happy with their lives. In The Giver, the busy and productive citizens of the Community are perfectly content with a life from which sex and gender roles, memories of suffering and even the perception of color have been eliminated in order to insure a smoothly running society. And even those in the matrix who come to realize they are being pacified by a cyber-dream so they can be used as batteries to power a kingdom of machines, often prefer that dream over the “red pill” that will awaken them to drab reality.

In each so-called dystopia, there is really only one person who is horrified by the situation: us, the audience, and those outlying, dysfunctional, anti-social characters in each story who represent us and our reactions. In order for these works to be properly called dystopian, in other words, the audience has to bring their own sense of revulsion to what well might seem a paradise to the characters involved.

Outside of fiction, what the whippersnappers call IRL—In Real Life—are we revolted by visions of engineered social perfection? I wouldn’t think so. One in six Americans uses mood-altering psychotropic drugs, according one recent study. Why should the medicated, or those who medicate them, object to the SOMA-induced happiness of Brave New World? The central outrage of The Giver is the extermination of unwanted infants. Abortion is the world’s leading cause of death by far, more than 40-million exterminated babies a year. Are we outraged? Not really. As the book’s “nurturer” says when he tosses one child’s corpse down a disposal chute: “Bye-bye, little guy!”

As for The Matrix, time will tell whether we will all be zucked into Zuck’s autistic metaverse, but the alacrity with which people retreated into cyber-life at the threat of a nasty flu, and the reluctance with which they are reemerging, does not augur any very popular attachment to the psychic battlefield of love and death that is RL.

Finally, there’s this. In almost all dystopian fiction, at the heart of the mechanized solution to life’s woes, is the neutralization or belittlement of sex and reproduction, most especially the humanizing physical and spiritual work of motherhood. In Brave New World, sex is reduced to a mere pastime and babies are constructed in incubators. In The Giver, the work of mothering is assigned to the lowest class of female. And in The Matrix, there are no real bodies whatsoever. (It is grimly symbolic that, due to technical difficulties, the first avatars of the Metaverse are invisible below the waist.) Are we truly unnerved by any of this? For those feminists who have elevated career above “mere” homemaking, and for gender activists who yearn to erase our binary sexual differences altogether, it is hard to think this aspect of dystopia would seem anything but a blessing.

In fact, a preference for dystopia has become a sort of intellectual signifier for just the sort of thinkers who congregate at the peak of the Bell Curve Meme—the guys who think its flashy as hell to display high IQ through blithe moral idiocy. Tech entrepreneur Shaan Puri recently went viral with a post that smugly described how soon “our virtual life will become more important than our real life.” And bestselling futurist Yuval Noah Harari says that Homo Sapiens will soon inevitably morph into Homo Deus, a near-immortal trans-being engineered for SOMA-style bliss. “You may debate whether it is good or bad,” he says, but the project of “re-engineering Homo Sapiens so that it can enjoy everlasting pleasure” can’t be avoided.

And yet—and yet—something in the heart rebels. Many of us—the vast majority of us, I’d bet—do not really want to solve the problems of humanity by ceasing to be human. We seek to rise above our flaws, not eradicate them, because that way lies spiritual growth. We like our gender roles, complete with their inequalities. There is untold beauty in them, and consolation for the tragedy of life. We even rather like, or at least respect, our mortality. It defines the parameters of our struggle to become ourselves and brings into relief our yearning for something beyond. We know dystopia at once when we see it in fiction. It’s only in reality that we fear to fear what we fear.

Because here’s another odd thing about dystopian fiction: the creator always imagines an avenue of escape from the hell of its perfections. In Brave New World, there are “the islands” for those who are “too self-consciously individual to fit into community-life.” In The Giver, there is “Elsewhere,” to which the young hero Jonas escapes carrying a baby doomed to extermination. In The Matrix, there is the now-famous red pill that takes you to Zion, the new Jerusalem.

New Jerusalem indeed—because what is Elsewhere if not the Kingdom of Heaven that is within us, that spiritual existence that persistently speaks to us out of our fleshly, mortal, gendered, all-too-human selves?

It is true religion—and only true religion—that informs our reluctance to evolve away from our humanity. This fact is ruefully depicted in Arthur C. Clarke’s science fiction novel Childhood’s End. The novel’s alien Overlords are sent to Earth to shepherd mankind into a higher stage of being, but they have to hide themselves from the objects of their benevolence. Why? It turns out the Overlords look exactly like Satan. Having had a premonition of their childhood’s end, humans have imaginatively demonized the midwives of their own evolution. Our Christian idea of evil, in other words, was created specifically to prevent Homo Sapiens from morphing into Homo Deus.

So, no doubt, it was. But if the Secret Knowledge is in some sense retrograde, it is only because it understands that the way forward is also the way back. As the Bell Curve Meme suggests, the sages we must become are akin to the child-like innocents we once were. Similarly, the paradise humanity lost in its infancy is the paradise that lies ahead—at least for those who are foolish and wise enough to opt out of dystopia and hightail it for Elsewhere. We need not abandon the scientific knowledge of modernity, but we must subjugate it to the needs of our humanity rather than allow its fleshless, sexless, motherless materialism to turn us into itself.

Because, spoiler alert, there is a God. Creation speaks his nature in the language of matter and our nature, made in his image, male and female, is meant to speak it back to him. The Word was made flesh and dwelt among us specifically to teach us how to make our flesh into the word and so become fully who we were meant to be.

That is the message of the Secret Knowledge. Uncool as it is, cool as we would seem, the best and brightest among us must not keep it secret anymore.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

When the church falls captive to woke ideology, secular truth-tellers win the day.

The Secret Knowledge is the antidote to lostness.