Dinesh D'Souza's 2,000 Mules raises forbidden questions.

Stalemate

2,000 Mules raises important questions, but most people have already decided on the answers.

Dinesh D’Souza’s new film has generated a great deal of new conversation about the 2020 election, but few hard-core enthusiasts on either side of the “Stolen Election” divide will be swayed. Those who are convinced nothing went wrong in 2020 are eager to dismiss the movie, no matter what intriguing questions it raises. Those who are already certain that the election was stolen are eager to accept it uncritically, despite its shortcomings. This dynamic is apparent in the many pieces which have already appeared either extolling or seeking to debunk 2000 Mules. An interview of D’Souza by the Washington Post’s Philip Bump perfectly illustrates this back-and-forth.

Both sides have a problem, which is that they can’t decide whether to apply legalistic or intuitive standards to the subject. When it comes to accepting the core claim of the movie—that paid organizers, or “mules,” deposited tens or hundreds of thousands of ballots in Georgia, Arizona, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and elsewhere—the film’s critics point out correctly that the film does not meet a courtroom standard. The case is based on voluminous data, the meaning of which is dependent almost entirely on inference.

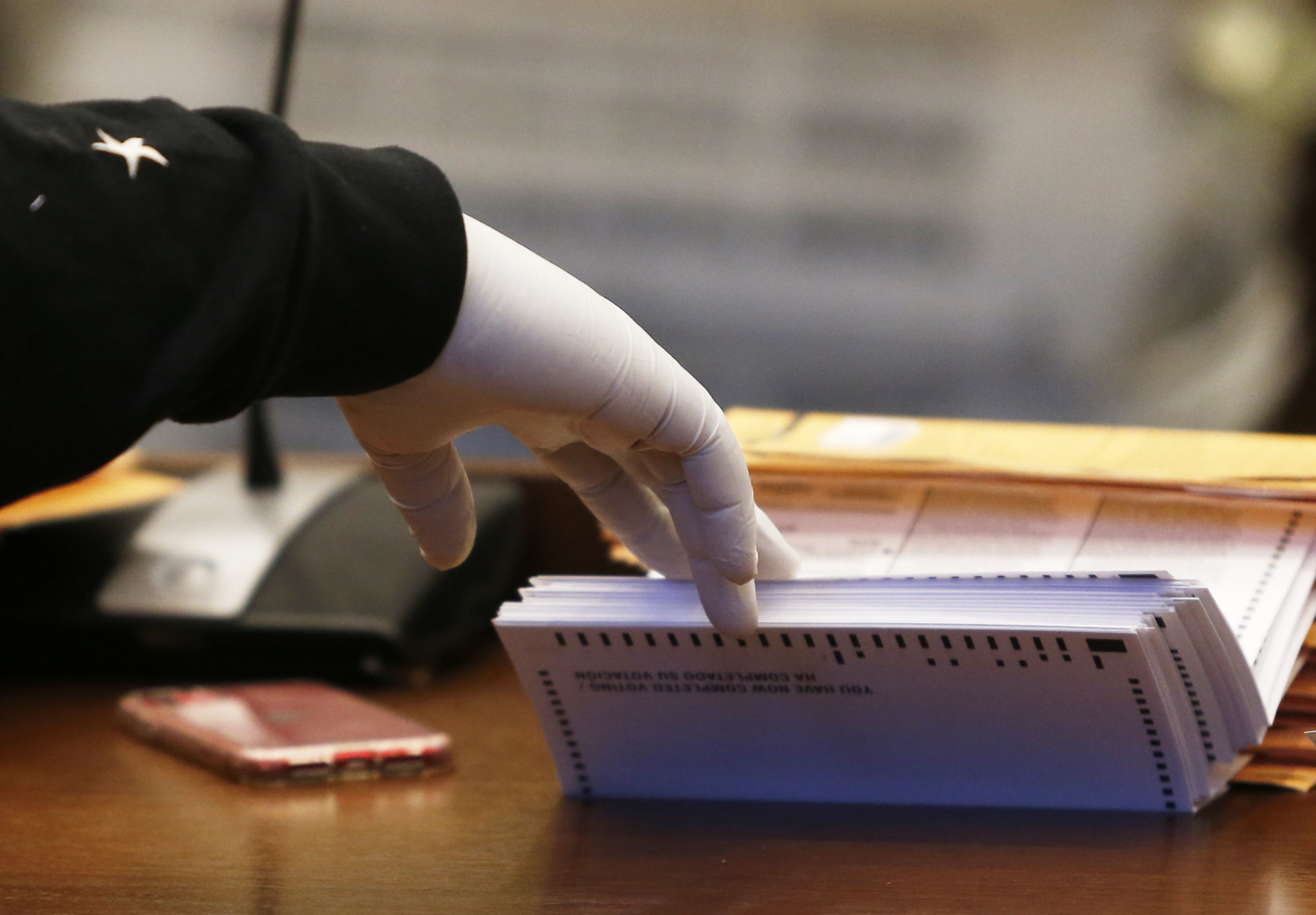

Could the man on the bicycle have taken a picture of the ballot drop box to prove to his sponsors that he had completed his task? Yes, but he might also have been taking a picture to post on social media, as election officials urged voters to do to stimulate turnout. Could the woman wearing latex gloves have been trying to hide fingerprint evidence? Yes, but she could also have been worried about COVID. Could individuals who made multiple visits close to a drop box been making multiple ballot dumps? Yes, but disputes about the precision of geo-tracking leave it an open question whether the proximity is sufficient to draw conclusions beyond a reasonable doubt.

Methods used to estimate the number of mules, and the average number of ballots deposited per mule, seem arbitrary, or at any rate not very obvious. None of the non-profits from which the mules were supposed to have collected ballots were ever identified. Nor, of course, could any evidence be offered about how the ballots in question were marked. The movie, as Ben Shapiro has observed, failed to effectively connect the dots.

Imagine, for a moment, that 2000 Mules was instantaneously available the week after election day 2020, and was shown to judges adjudicating President Trump’s fraud claims. It would have changed nothing. No election would (or should) be overturned on the basis of inferential arguments alone. The movie, which came out a year and a half after election day and still cannot be considered decisive, should put to rest any lingering notion that the electoral vote count should have been delayed until fraud claims were investigated and conclusions reached. We would still be waiting. (Of course, the constitutional objections raised to those notions by Joseph Bessette in the Claremont Review of Books should actually be paramount.)

Supporters of the film’s premise respond intuitively. Why on earth would these people return to the vicinity of the drop boxes over and over? Who repeatedly goes to the library at 2 A.M.? Who can really doubt how the ballots were marked? What about the video footage of individuals stuffing large numbers of ballots into collection boxes? And what about the whistleblower from Yuma, whose darkened figure related a tale of vote trafficking in Arizona?

All good questions. The critics do not seem to have good answers to these questions. Instead, they fall back on the legalistic argument that it isn’t their job to explain things. D’Souza is the one making an incendiary argument, they say, and the burden of proof is on him. His response: Use common sense. Common sense, however, depends on a common framework, which supporters and opponents of the Stolen Election narrative do not share. The field is wide open for confirmation bias on both sides.

Switching Sides

What about the broader implication of the film—that, without the alleged mules, Trump would have won the election? Here the roles are reversed. The formerly legalistic opponents of the film’s premise turn intuitive, or at least non-legalistic. Even if the alleged scheme is true—and they deny it is—whether or not they were deposited in accord with election rules of the states involved, the ballots themselves were valid ballots. To this point they quote the Wisconsin testimony of True the Vote’s Catherine Engelbrecht, who said before a state legislative hearing, “I want to make very clear that we’re not suggesting the ballots that were cast were illegal ballots.” Though rules may have been broken, the end result of the election was not distorted.

On the other hand, at this point, D’Souza adopts legalism. Even if the ballots were valid representations of the choices of actual voters—he is doubtful about this, but cannot prove his doubts justified—the way in which they were delivered makes them illegal votes. If his (more than a bit murky) calculations are correct, enough illegal votes should be subtracted in key states to give Trump the win.

How should we assess the probability that a widespread ballot-trafficking scheme was undertaken by Democrats and progressive non-profits in 2020? We know that on a much smaller scale, such things do happen (as in the 2018 election in the Ninth Congressional District of North Carolina). As shown by Mollie Hemingway in Rigged and John Fund and Hans von Spakovsky in Our Broken Elections, we also know that other wonky things happened in 2020, including legally and constitutionally dubious election rule changes in numerous states and a serious absentee ballot scam in Wisconsin nursing homes. Until there is a full accounting of the $470 million spent by Mark Zuckerberg on voter mobilization, questions about where that money ultimately went will remain. And what to make of the whistle blower from Yuma, and the one from Georgia who D’Souza says inspired the entire investigation (though he did not appear in the film)? It is, at least, a more plausible story than the Kraken’s Dominion voting machine theory or claims that Democrats manufactured huge quantities of votes during the lull in counting late on election night.

At the same time, what to make of the fact that there are, apparently, only one or two whistleblowers in an operation that allegedly spanned multiple states, employed up to 54,000 mules, and involved hundreds of thousands of ballots? If inference and deduction are going to be the coin of the realm, there is much that points in the direction of the alleged scheme not existing on the scale that is alleged, and in any event not being decisive to the outcome.

The more anomalous the result, the harder one should look for extraordinary explanations; the less unexpected the result, the less likelihood that it was the result of foul play. Had Ronald Reagan in 1984 suddenly lost to Walter Mondale, one could reasonably grasp at even the mere inference of fraud as an explanation. But Donald Trump was no Ronald Reagan. Whether one consults the RealClearPolitics polling average or 538.com, there was not a single day of Trump’s presidency that a majority, or even a plurality, of Americans said they thought he was doing a good job as president.

For nearly his entire presidency—starting around January 27, 2017 and continuing unbroken through January 20, 2021—his job approval ratings were underwater, with more disapproving than approving. For his entire presidency, from the first day to the last, his favorability ratings—that is, Americans’ assessment of Trump as a person rather than his performance as president—were also underwater. For his entire presidency, a solid majority of Americans—in November 2020, an overwhelming majority—said the country was headed in the wrong direction. Having no room for error and with a ceiling of about 47% support, Trump then presided over a pandemic, a sharp economic reversal, and a summer of riots and discord. Trump’s loss should have surprised no one. Extraordinary explanations seem unnecessary.

Then there were the pre-election polls, undertaken by a wide range of reputable survey firms, some of which were Republican-leaning. The RealClearPolitics archive of head-to-head polls contains 230 presidential matchups between Trump and Joe Biden from mid-2019 through election day. Trump led in exactly five of the 230, and in only one after February 2020—a Rasmussen survey two months before election day in which the president led his challenger by 1 percentage point.

It may be said that skilled fraudsters will aim to dump just enough ballots to produce a plausible victory, but this operation had to manage that minutely-calibrated task days or weeks before legitimate vote totals were known. And it had to be done across multiple states. In addition to the practical improbability of this scenario in the abstract, the normal evidence one might expect of inflated vote totals does not appear in 2020.

On election day, the RCP polling average showed Biden at 51%, Trump at 44%. Had massive fraud manufactured hundreds of thousands of votes in Biden’s favor, one would expect that his reported vote would significantly surpass his final national poll number. Yet when the totals were reported, Biden had—51%. Trump ended with a reported total of 47%, better than the polls predicted. State polling averages in the six key states that reported a narrow victory for Biden—Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—showed that Trump had trailed for months in every one but Georgia, where he had frequently traded leads with Biden and had recently regained a small advantage, within the margin of error.

If there were enough ballots to pad Biden’s totals in all the relevant key states, one would also expect that his reported percentages there would have been significantly higher than what the exit polls indicated. This was not the case.

To the contrary, in Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, Biden’s reported totals were actually a fraction of a percent lower than his exit poll numbers; in Arizona and Nevada only a fraction of a percent higher. All were within the margin of error. How there could be a massive infusion of fraudulent votes without driving the reported vote totals far out of congruence with the exit polls (which also surveyed mail voters) is an ongoing mystery.

Banging the Drum

In the end, people believe what they want to believe. So why are so many people eager to believe the story told in 2000 Mules without grappling with its shortcomings?

First, other underhanded tactics indisputably utilized in 2020 by Democrats and their allies lend credence to the story. Moreover, one feature of human nature is that it is always preferable to believe your opponents cheated than to believe that your countrymen rejected your guy. Today, when friendly media bubbles are the rage, it may be easier to believe, too. Democrats, for their part, have been demonstrating this phenomenon for a long time, whether in charges that Reagan won by conspiring with the Ayatollah, that Bush the elder won through a dirty racist campaign, that his son was anointed by the Supreme Court then rigged Diebold machines in Ohio, or that Trump colluded with Russia. Democratic members of Congress have objected to electoral votes in the last three Republican presidential wins.

The Stolen Election narrative also has legs because Joe Biden is so bad at being president. People ask, How could he have won? The most likely answer—that he successfully turned the election into a referendum on an unpopular president in which he himself was little more than an inert prop—is unsatisfying to many. Trump supporters have difficulty grasping how successful Trump was at mobilizing the opposition.

Not least, a major contributing factor is that Trump himself continues banging the drum and now seems solely motivated by the desire to redeem his loss, which he cannot acknowledge for reasons of both political necessity and personal narcissism. Not for nothing were the founders concerned about the potential hazards of demagoguery.

Altogether, 2000 Mules raises questions that should be seriously investigated by the authorities. In so doing, the film makes the case for legislative limits on mail ballot voting and vote harvesting as well as for putting an end to unsupervised ballot collection boxes and private funding of election administration. When it attempts to go farther, though, its reach exceeds its grasp, and it pours fuel on a fire that is already emitting more heat than light.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Americans must reckon with what the courts failed to resolve.

A conversation with Dinesh D’Souza about his documentary, 2000 Mules.