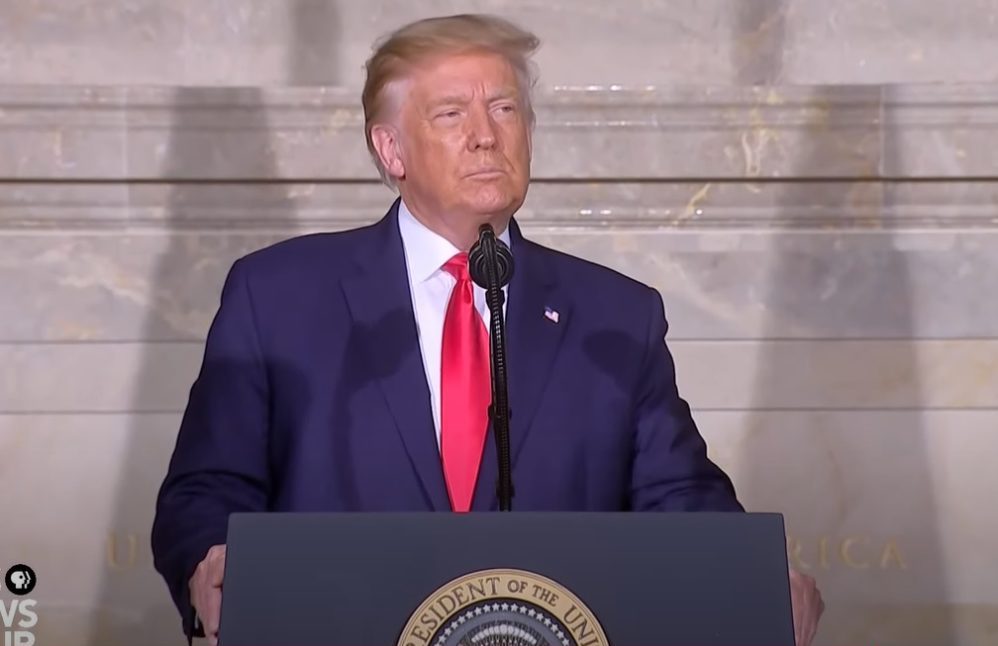

Self-criticism, Progressivism, and post-modernism.

Lincoln and the Cherry Tree

History sustains us when our ties to one another become frayed.

We all know that Abraham Lincoln was a voracious reader. He had essentially no formal education and acquired his peerless sense of the English language from his reading, including Shakespeare’s plays and the King James Bible. But it appears that he read almost no history in his younger days. The sole exception that we know of was Mason Weems’s 1799 biography of George Washington, a tome few would read today, and certainly not for its accuracy. After all, it’s the book from which the fable of young George chopping down the cherry tree came.

The mature Lincoln went on to develop a more informed and sophisticated understanding of history. And yet elements of Weems’s History stayed with him all his life, influencing his view of the American Revolution and the Civil War, and reflecting his fundamental values.

We know this because in February of 1861, forty years after he first read Weems’s book, Lincoln drew upon it. He was on his way from Illinois to Washington to be inaugurated as President. It was a time of extraordinary tension in the land, with Southern states voting to drop away from the Union one after another, in response to Lincoln’s election.

Lincoln stopped off in Trenton on his way to Washington, and in a short but powerful speech to the New Jersey State Senate, recalled the effect of Weems’s book on him as a young man. He particularly remembered the pivotal Battle of Trenton: “I remember all the accounts of the battlefield and struggles for the liberty of the country, and none fixed themselves upon my imagination so deeply as the struggle here at Trenton.”

The crossing of the river, the contest with the Hessians, the great hardships endured at that time, all fixed themselves on my memory more than any single revolutionary event…. I remember thinking then, boy even though I was, that there must have been something more than common that those men struggled for.

That “something” was “even more than National Independence, something that held out a great promise to all the people of the world for all time to come.” It was “the perpetuation of the Union, the Constitution, and the liberties of the people, in accordance with the original idea for which that struggle was made.”

What a lot for a story to do! It helped to form a vision of the American past—a vision that was both inspiring and true—that sustained him through the dark days to come.

Note too that, although himself a fierce opponent of slavery, Lincoln did not focus on Washington’s history as a slaveowner, even though he knew of it. He did not entertain the view, fashionable among Southern planters then and New York journalists now, that the nation was founded on slavery. No, he insisted, it was founded on other principles entirely, principles of liberty and equality and self-rule that were something new in the world, principles that America was born to champion. He was right then and he is right now.

So what are we to conclude from this? Do historians need to retool and start writing inspiring fables like those of Mason Weems? No, absolutely not. History must be based on truth, not on myth. But we need to remember that one of the civic functions of history is to serve as an expression of shared memory, imparting to each generation a sense of membership in its own society, a sense of living connection to its own past.

We need that today, more than ever. As John Dos Passos wrote,

In times of change and danger when there is a quicksand of fear under men’s reasoning, a sense of continuity with generations gone before can stretch like a lifeline across the scary present.

That sense of continuity was something Lincoln could summon and draw upon, to strengthen him in enduring our Nation’s greatest time of change and danger. Our young people deserve nothing less. We are failing them, and our country, as long as we fail to give them a rich and sustaining sense of their own past, a sense that is both truthful and inspiring. It’s high time for that to change.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

America's young people are miserable and angry. Universities are to blame.

The 1619 Project isn't the only curriculum turning students against America.

Our heroes will never be forgotten.

Revisionism disrespects students and undermines our regime.

Who controls the past, controls the future.