Since Jaffa wrote "Reichstag" in 1989, the campus left has adorned its ideology with a few new terms—but its underlying relativism remains the same.

Beauty Alone Won’t Save Us

Absent the teaching of human truth, absolutism preys on our atomized youth.

Heather Mac Donald argues that relativism is not one of the modern academy’s predominant features, and it wouldn’t matter if it was. She doesn’t believe that “truth” is a relevant category in university life, holding instead to “knowledge of our cultural inheritance” as well as stimulating a student’s love of beauty and wisdom. Where Jaffa believes education necessarily devolves into unreason and subjectivism unless it is connected to “trans-historical and trans-cultural” truths, Mac Donald argues that the contingency of human affairs means we should be content with simply appreciating the best of what our own culture has to offer.

Mac Donald rightly identifies “tribalism” as one of the corrupting influences in the modern academy. I was recently at a conference where a professional historian began her talk by saying that anytime she reads a book the first and only question she asks is “where are the women?” This kind of crabbed hermeneutic is condemned by Jaffa and Mac Donald alike. But whereas Jaffa gives a thorough account of its irrationality, and offers a solution to it by believing we can say something true about human beings, Mac Donald repeats the well-worn skepticism that truth is fungible and therefore useless. Instead, schools should immerse students in “great works.” But why should a school engage in her project of passing along these great works as an inheritance to the young? Can they provide an explanation of what makes them great? Are they great simply because they’re beautiful, or are they great because they are passing along something essential about who we are—even if it’s the truth that we are creatures who love and need beauty?

Nonetheless, Mac Donald is not wrong when she suggests that relativism is not the main problem of the modern academy, even if she doesn’t see tribalism as a form of relativism. She identifies “hate” as the problem on campuses, but there is nothing new about hate, as Jaffa notes in his reflections on the 60’s.

Neither is Mac Donald wrong when she claims that the mask of non-judgmentalism covers a pernicious tendency to judge. That can’t be explained by reference to relativism so much as by reference to the remarkably fragile selves who inhabit contemporary campuses. This fragility can’t be placed on “relativism” or an abandonment of rationality, although it does imply a loss of a truth about who we are as human beings.

The truth that is missing about ourselves involves both an epistemological and a sociological dimension. We have become increasingly isolated, estranged from one another, alienated from ourselves and nature, and deracinated. This atomism will naturally result in efforts to buttress our fragile selves by finding some sort of connection. Sexual identity may look like another form of expressive individualism, but in fact it compensates for anxiety by either demanding recognition in its interplay with authenticity, or by sublimating personal identity into a group one. The withholding of recognition is experienced as a negation of identity, and thus an act of violence, which is why “microaggressions” and “safe spaces” have become the coinage of the realm.

The biggest challenge on campus life comes not from skeptics on the faculty—Mac Donald is right about this—but from absolutists in student life who find purchase for their ideological deformations precisely because they understand that the students with whom they work are lost and lonely. I can tell you from my experience with these students that sound arguments and reason mean nothing. You can point out their logical incoherence, or their selective and inconsistent application of principles, or that they are working against their own interests or the truth of who they are. But it won’t matter, because the underlying problem is that they are unanchored: they try to find some mooring somewhere and if the one you give them isn’t stable, they’ll take whatever rickety one is most easily available.

Schools are happy to have these lost but excellent sheep: since they arrive disconnected, they can be easily connected either to the ideology of identity politics or to the closely related cosmopolitan dreams of most faculty. Indeed, the central conceit of the modern academy is its (false) conviction that it is “creating leaders” in a “global society.” This imputation is no doubt a result of modern faculty’s complete deracination and alienation.

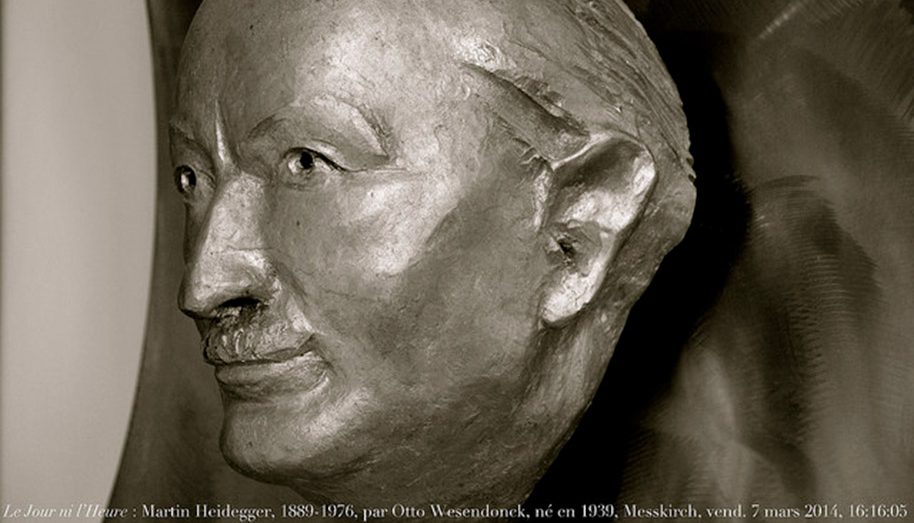

Mac Donald understands you have to offer students stories—concrete things they can connect themselves to—and not airy arguments about “truth.” This has little to do with reason and everything to do with images. But where Mac Donald goes wrong, and what Jaffa gets right, is that an image, as he says, is simply a way by which the form of a thing can be separated from its matter. Mac Donald fails to see this is the key insight of Jaffa’s essay, so that when she offers “books” or “beauty” or “heritage” as a response to the crisis of the academy, she is mistaking the image for the reality and truth it carries.

Mac Donald seeks to separate beauty from its historical relation to the true and the good. She believes this severing should be accomplished not for normative reasons but for practical ones; namely, the variety of competing truth claims, their indeterminateness, and their intrinsic relationship to personal preferences.

It’s not clear, however, why beauty should be so exempted or could ever carry the weight she assigns to it. It would seem that beauty, of any in the great triumvirate, is especially subject to subjectivism’s corrosion.

Mac Donald claims that instruction in beauty will be sufficient to head off the crisis. Her impeccable taste and great passion for beauty (she is a first-rate opera critic) might bias her in favor of its elevating power; all the arguments she makes against truth, of course, can just as easily be made against beauty. She seems to believe cultivation in taste will create the class of “gentlemen” we need, whose social capital will leaven the enterprise. But I doubt her recommendation would effect any substantive change in our educational institutions. Such changes will require attending to our communal natures as part of the search for truth.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

We may never find a grand, unified theory of the “single truth," but we do not need it to know that men are not horses and beauty is truly good.

Without a common understanding of the human person and the human good, academia is reduced to job training, politics, or consumerism.

Both the burning of the Reichstag and the decline of the American university resulted from the choices of philosophers. Jaffa’s final address is a condensed version of the book Allan Bloom should have written, but couldn’t.

"Relativism," contra Jaffa (and Bloom), was merely administrative compromise. But the academy no longer believes all sin is relative...

What's the Root of Academic Rot?