Thanksgiving remains one of our few unifying traditions.

2020: A Retrospective From 2025

Donald Trump and the Altogether True and Amazing Origin of the United American Counties.

2020 marked an epoch in American history, standing alongside 1865, 1787, and 1776. First there was the COVID-19 pandemic, then there were the racial protests and riots throughout the summer, and then there was the disputed presidential election. Finally and most cataclysmically, though, 2020 witnessed the initial formation of the United American Counties (UACo) within the former United States of America. Five years later, it is only now becoming possible to assess the most important causes and consequences of this momentous development for American political society.

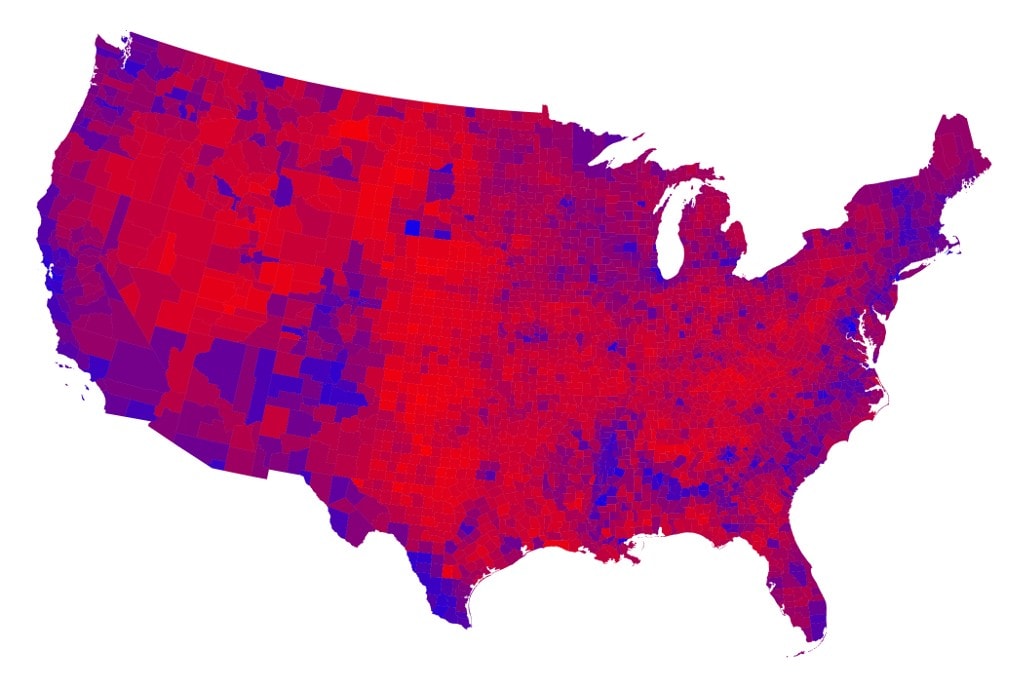

As with most politically revolutionary events, the Declaration of UACo Independence was almost entirely unforeseen before it occurred, but almost inevitable in hindsight. By the early 2010s two things were clear: (1) Americans had become increasingly polarized in their worldviews and political beliefs; and (2) These polarized halves of the U.S. were increasingly sorting themselves into either urban or suburban/rural areas. Trump’s election in 2016 put a spotlight on these political realities; as Trump frequently boasted, the 2016 electoral map looked like a sea of red surrounding islands of blue. In 2020, that situation was essentially unchanged.

97% of land area in the U.S. constituted rural counties. Trump’s support within these counties was high and enthusiastic both in 2016 and 2020. Within the remaining 3% of the geographical U.S.—the big cities—anti-Trump sentiment was equally high and enthusiastic.

The 2020 election was the perfect storm for a confrontation between these two factions. It looked like Trump was winning on election day, and then the mail-in ballots handed an apparent victory to Biden. Although widespread electoral fraud wasn’t uncovered by the protracted legal investigation that followed, the die had been cast. Trump and his supporters thought the election had been stolen, and that Trump was the legitimate president of the U.S.

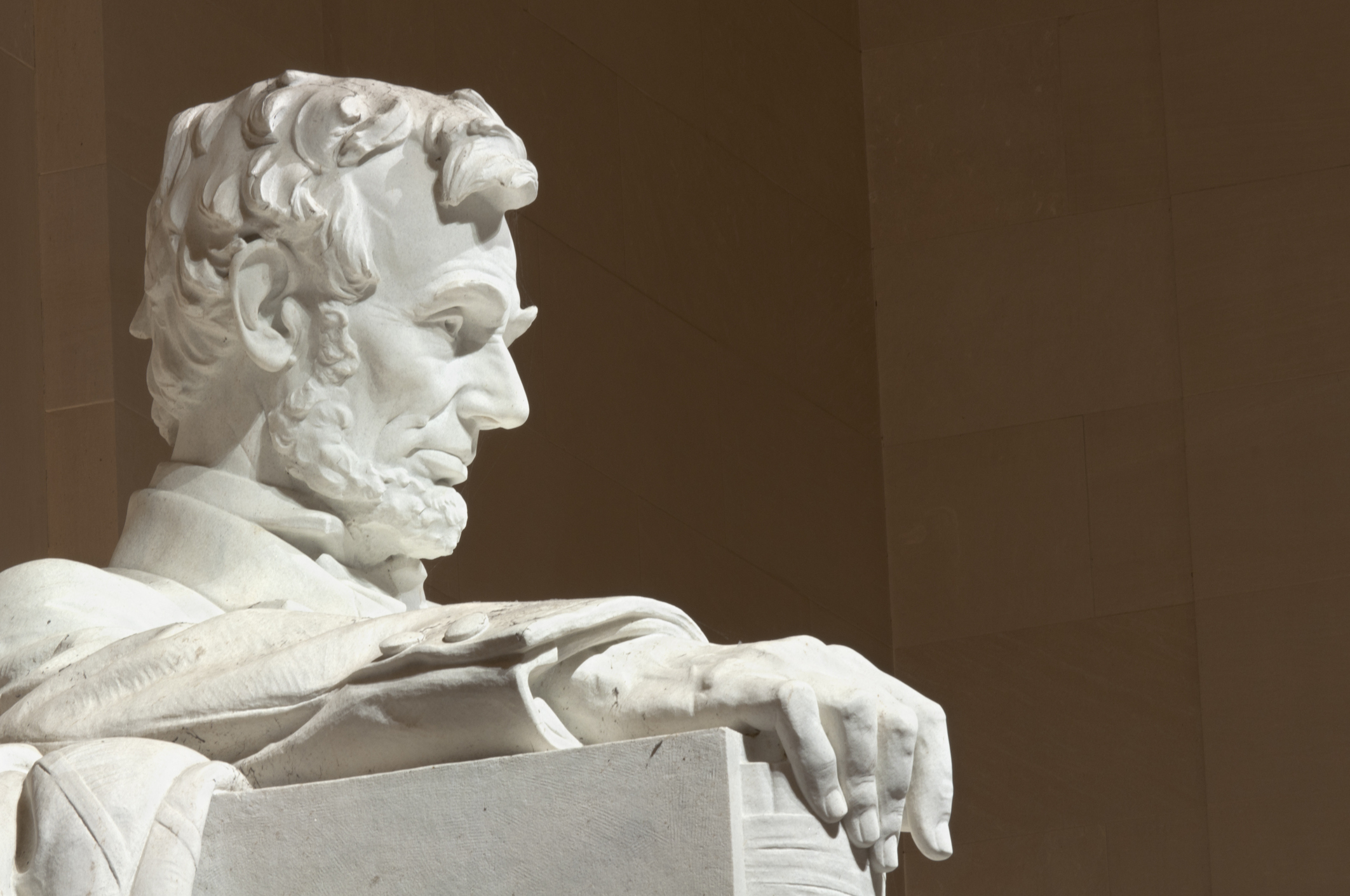

If it had only been the election dispute, tensions may have dissipated over time. Trump supporters may have learned to live with a Biden presidency, especially given GOP victories at the state level and in Congress. The problem was that the election dispute coincided with a deep polarization of worldviews and American historical narratives that had been building for decades. This polarization had proceeded to the extent of annihilating any possible common ground, rendering attempts at compromise or a “live and let live” approach impossible. We had become two Americas; and, as Lincoln had said, “a house divided against itself cannot stand.”

In 1861, the outcome of this intractable situation was state secession. The division at this time was between slave states and free states. In 2020, the division was not so much between states as between rural and urban counties within states. In 1861, Lincoln was able to marshal the political will, the moral justification, and the economic and military resources necessary to maintain the original constitutional union by force. In 2020, none of these factors was present: Biden proved to be no Lincoln, and the country was too exhausted from the events of 2020 to muster an extended effort to compel union through force.

An America Altogether New

The rapid dissemination of the Declaration of UACo Independence in December 2020 provided the motivation and justification for the formation of a new political society within the former U.S.

Its “List of Principles” effectively encapsulated the worldview of American political conservatives and echoed the Declaration of 1776: it endorsed “the equal natural rights bestowed by God on all human beings,” “limited and local self-government,” “the traditional family begun in marriage between one man and one woman,” and “the free market economy.”

And its “List of Grievances” against the progressive liberal orthodoxy entrenched in corrupt urban areas supplied the relevant context for separation: chief among the complaints were “the suppression of freedom of speech” through cancel culture and thought policing, “the eclipse of local self-government by distant ruling elites,” “the replacement of equality under the law with identity politics,” “the rejection of the American political tradition,” and “the introduction of policies destructive of economic freedom.”

As the Declaration was supplying the inspiration, Trump’s team supplied the necessary perspiration by working quickly and tirelessly to rally support and official endorsement from the hundreds of counties that had supported his election to office weeks before. The rapidity with which this was accomplished was crucial to its ultimate success, and almost unbelievable in hindsight. They were aided by the establishment of efficient systems of communication running throughout the hundreds of rural and suburban counties sympathetic to the movement—the so-called “Town Crier Committees.” This system, working in conjunction with self-dubbed “Minutemen” vigilante groups, provided the coordinated resistance necessary to enforce the county endorsements of Trump’s leadership.

The preexistence of county government and law enforcement structures aided the transition as well. Early efforts by state governors to use state police and National Guard troops to compel adherence to state laws across vast UACo areas met with such resistance, both externally and internally, that they were quickly deemed impracticable. With the adoption of the provisional Constitution for the United American Counties in January 2021 by more than 500 counties—a number that would grow to nearly 2,000 by May of that same year—the stage was set for a decision by the newly-inaugurated Biden and the areas remaining under his jurisdiction. Would he go to war with Trump’s counties and attempt to compel union as Lincoln had?

A Separate Peace

Many factors weighed against this decision. There was, first, the lack of the kind of moral momentum that the abolition movement had supplied in the decades leading up to the Civil War. As Lincoln had long insisted, the controversy that brought on the Civil War was the question of whether slavery was right or wrong. The seceding states took a stand for its rightness, and the Union states took a stand for its wrongness. In 2020, there was no moral controversy that would come close to this kind of stark alternative; no higher ideal that would plausibly justify shedding the blood of fellow Americans.

Secondly, although Biden technically assumed control of the powerful U.S. military, he and his advisors were justifiably wary of issuing an immediate order to mobilize this force—a majority of whom had voted for Trump in the election—against such a widespread movement involving innumerable family connections and divided loyalties for military service members. There was the problem of supply chains for manufacturing and transportation; since these relied upon and ran directly through large swaths of UACo-controlled territory, they could be easily disrupted either by the withholding of necessary support or through sabotage.

There was also the immense practical difficulty of fighting a war against guerilla-type forces dispersed across more than 75% of the land area of the U.S. As the British had come to realize in the American Revolutionary War, such a conflict may well have been unwinnable, despite a large disparity in raw military and economic might.

In the face of these obstacles to compelling union through force, Biden had no choice but to negotiate with Trump. The American Friendship Accords, finalized on the anniversary of election day the year before (November 3, 2021), officially established two sovereign nations (the United American Counties and the United American Cities), averted large-scale violent conflict, and established the economic and military agreements necessary to maintain cooperation between the two new political entities at a level similar to what had existed before.

In 2025, just five short years after the tumultuous period of 2020-21, we seem to have entered a new era of American peace and prosperity. Relieved from the incessant tension of trying to reconcile fundamentally irreconcilable worldviews under a common government, polarized American society has achieved a kind of equilibrium. Common moral and political principles are once again able to provide the foundation for productive debate and coherent public policy within both the UACo and the UACi. The freedom of economic exchange and personal movement between the two has facilitated the growth of new ties of continental friendship where before there was polarization and enmity.

It may still be too early to pronounce judgment on the new political situation in the former U.S. But so far, looking back on 2020 seems to confirm the old proverb: It’s always darkest just before the dawn.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

We have flirted with disaster before. Now we must avert it.

Following Trump's lead—and Lincoln's.